- Single file deployment and executable

- Output differences from .NET 3.x

- API incompatibility

- Attaching a debugger

- Including native libraries

- Other considerations

- Exclude files from being embedded

- Include PDB files inside the bundle

- Compress assemblies in single file app

- Publish a single file app — sample project file

- Publish a single file app — CLI

- Publish a single file app — Visual Studio

- Publish a single file app — Visual Studio for Mac

- Own your bits

- The real power of Linux executables

- What involves executing a file

- The kernel side of things

- ELF binaries

- What about scripts?

- Execute anything with bitfmt_misc

- References

Single file deployment and executable

Bundling all application-dependent files into a single binary provides an application developer with the attractive option to deploy and distribute the application as a single file. This deployment model has been available since .NET Core 3.0 and has been enhanced in .NET 5.0. Previously in .NET Core 3.0, when a user runs your single-file app, .NET Core host first extracts all files to a directory before running the application. .NET 5.0 improves this experience by directly running the code without the need to extract the files from the app.

Single File deployment is available for both the framework-dependent deployment model and self-contained applications. The size of the single file in a self-contained application will be large since it will include the runtime and the framework libraries. The single file deployment option can be combined with ReadyToRun and Trim (an experimental feature in .NET 5.0) publish options.

Single file deployment isn’t compatible with Windows 7.

Output differences from .NET 3.x

In .NET Core 3.x, publishing as a single file produced exactly one file, consisting of the app itself, dependencies, and any other files in the folder during publish. When the app starts, the single file app was extracted to a folder and run from there. Starting with .NET 5, only managed DLLs are bundled with the app into a single executable. When the app starts, the managed DLLs are extracted and loaded in memory, avoiding the extraction to a folder. On Windows, this means that the managed binaries are embedded in the single-file bundle, but the native binaries of the core runtime itself are separate files. To embed those files for extraction and get exactly one output file, like in .NET Core 3.x, set the property IncludeNativeLibrariesForSelfExtract to true . For more information about extraction, see Including native libraries.

API incompatibility

Some APIs are not compatible with single-file deployment and applications may require modification if they use these APIs. If you use a third-party framework or package, it’s possible that they may also use one of these APIs and need modification. The most common cause of problems is dependence on file paths for files or DLLs shipped with the application.

The table below has the relevant runtime library API details for single-file use.

| API | Note |

|---|---|

| Assembly.Location | Returns an empty string. |

| Module.FullyQualifiedName | Returns a string with the value of or throws an exception. |

| Module.Name | Returns a string with the value of . |

| Assembly.GetFile | Throws IOException. |

| Assembly.GetFiles | Throws IOException. |

| Assembly.CodeBase | Throws PlatformNotSupportedException. |

| Assembly.EscapedCodeBase | Throws PlatformNotSupportedException. |

| AssemblyName.CodeBase | Returns null . |

| AssemblyName.EscapedCodeBase | Returns null . |

We have some recommendations for fixing common scenarios:

To access files next to the executable, use AppContext.BaseDirectory.

To find the file name of the executable, use the first element of Environment.GetCommandLineArgs(), or starting with .NET 6 use the file name from ProcessPath.

To avoid shipping loose files entirely, consider using embedded resources.

Attaching a debugger

On Linux, the only debugger which can attach to self-contained single-file processes or debug crash dumps is SOS with LLDB.

On Windows and Mac, Visual Studio and VS Code can be used to debug crash dumps. Attaching to a running self-contained single-file executable requires an extra file: mscordbi. .

Without this file Visual Studio may produce the error «Unable to attach to the process. A debug component is not installed.» and VS Code may produce the error «Failed to attach to process: Unknown Error: 0x80131c3c.»

To fix these errors, mscordbi needs to be copied next to the executable. mscordbi is publish ed by default in the subdirectory with the application’s runtime ID. So, for example, if one were to publish a self-contained single-file executable using the dotnet CLI for Windows using the parameters -r win-x64 , the executable would be placed in bin/Debug/net5.0/win-x64/publish. A copy of mscordbi.dll would be present in bin/Debug/net5.0/win-x64.

Including native libraries

Single-file doesn’t bundle native libraries by default. On Linux, we prelink the runtime into the bundle and only application native libraries are deployed to the same directory as the single-file app. On Windows, we prelink only the hosting code and both the runtime and application native libraries are deployed to the same directory as the single-file app. This is to ensure a good debugging experience, which requires native files to be excluded from the single file.

Starting with .NET 6 the runtime is prelinked into the bundle on all platforms.

There is an option to set a flag, IncludeNativeLibrariesForSelfExtract , to include native libraries in the single file bundle, but these files will be extracted to a directory in the client machine when the single file application is run.

Specifying IncludeAllContentForSelfExtract will extract all files (even the managed assemblies) before running the executable. This preserves the original .NET Core single-file deployment behavior.

If extraction is used the files are extracted to disk before the app starts:

- If environment variable DOTNET_BUNDLE_EXTRACT_BASE_DIR is set to a path, the files will be extracted to a directory under that path.

- Otherwise if running on Linux or MacOS, the files will be extracted to a directory under $HOME/.net .

- If running on Windows, the files will be extracted to a directory under %TEMP%/.net .

To prevent tampering, these directories should not be writable by users or services with different privileges, (so not /tmp or /var/tmp on most Linux and MacOS systems).

In some Linux environments (for example under systemd) the default extraction will not work because $HOME is not defined. In such cases it’s recommended to set $DOTNET_BUNDLE_EXTRACT_BASE_DIR explicitly.

For systemd a good alternative seems to be defining DOTNET_BUNDLE_EXTRACT_BASE_DIR in your service’s unit file as %h/.net , which systemd expands correctly to $HOME/.net for the account running the service.

Other considerations

Single-file application will have all related PDB files alongside it and will not be bundled by default. If you want to include PDBs inside the assembly for projects you build, set the DebugType to embedded as described below in detail.

Managed C++ components aren’t well suited for single-file deployment and we recommend that you write applications in C# or another non-managed C++ language to be single-file compatible.

Exclude files from being embedded

Certain files can be explicitly excluded from being embedded in the single-file by setting following metadata:

For example, to place some files in the publish directory but not bundle them in the single-file:

Include PDB files inside the bundle

The PDB file for an assembly can be embedded into the assembly itself (the .dll ) using the setting below. Since the symbols are part of the assembly, they will be part of the single-file application as well:

For example, add the following property to the project file of an assembly to embed the PDB file to that assembly:

Compress assemblies in single file app

Starting with .NET 6, single file apps can be created with compression enabled on the embedded assemblies. Set EnableCompressionInSingleFile property to true to achieve this. The produced single-file will have all of the embedded assemblies compressed which can significantly reduce the size of the executable. Compression comes with a performance cost. On application start, the assemblies must be decompressed into memory, which takes some time. It’s recommended to measure both the size impact and startup cost impact of enabling compression before using it as the impact varies a lot between different applications.

Publish a single file app — sample project file

Here’s a sample project file that specifies single-file publishing:

These properties have the following functions:

- PublishSingleFile — Enables single-file publishing. Also enables single-file warnings during dotnet build .

- SelfContained — Determines whether the app will be self-contained or framework-dependent.

- RuntimeIdentifier — Specifies the OS and CPU type you are targeting. Also sets true by default.

- PublishReadyToRun — Enables ahead-of-time (AOT) compilation.

Notes:

- Single-file apps are always OS and architecture-specific. You need to publish for each configuration, such as Linux x64, Linux ARM64, Windows x64, and so forth.

- Runtime configuration files, such as *.runtimeconfig.json and *.deps.json, are included in the single file. If an additional configuration file is needed, you can place it beside the single file.

Publish a single file app — CLI

Publish a single file application using the dotnet publish command.

to your project file.

This will produce a single-file app on self-contained publish. It also shows single-file compatibility warnings during build.

Publish the app as for a specific runtime identifier using dotnet publish -r

The following example publishes the app for Windows as a self-contained single file application.

dotnet publish -r win-x64

The following example publishes the app for Linux as a framework dependent single file application.

dotnet publish -r linux-x64 —self-contained false

should be set in the project file to enable single-file analysis during build, but it is also possible to pass these options as dotnet publish arguments:

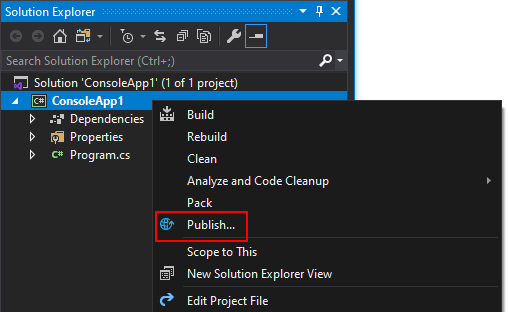

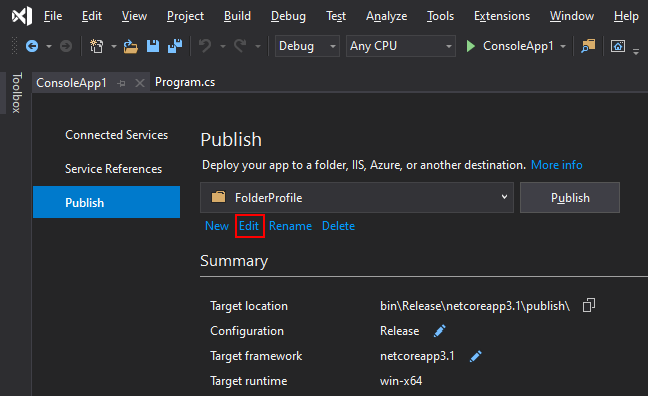

Publish a single file app — Visual Studio

Visual Studio creates reusable publishing profiles that control how your application is published.

to your project file.

On the Solution Explorer pane, right-click on the project you want to publish. Select Publish.

If you don’t already have a publishing profile, follow the instructions to create one and choose the Folder target-type.

Choose Edit.

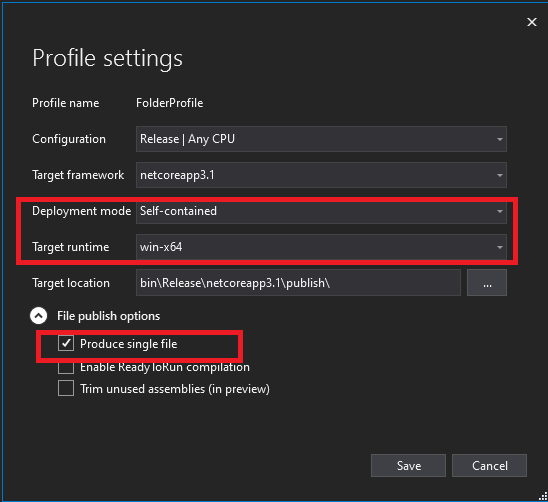

In the Profile settings dialog, set the following options:

- Set Deployment mode to Self-contained or Framework-dependent.

- Set Target runtime to the platform you want to publish to. (Must be something other than Portable.)

- Select Produce single file.

Choose Save to save the settings and return to the Publish dialog.

Choose Publish to publish your app as a single file.

Publish a single file app — Visual Studio for Mac

Visual Studio for Mac doesn’t provide options to publish your app as a single file. You’ll need to publish manually by following the instructions from the Publish a single file app — CLI section. For more information, see Publish .NET Core apps with .NET Core CLI.

Источник

Own your bits

Technology with a focus on Open Source

The real power of Linux executables

What happens when a file gets executed in Linux? What does it mean that a file is executable? Can we only execute compiled binaries? What about shell scripts then? If I can execute shell scripts, what else can I execute? In this article we will try to answer those questions.

What involves executing a file

Starting from the basics, let’s try to understand what happens when we type the following in our terminal

The way our programs in the userspace interact with the kernel is through system calls. In practice we need to interact with the kernel to do almost anything that is interesting, such as printing output, reading input, reading files and so on.

The syscall that is in charge of executing files is the execve() system call. When we are coding, we normally access it through the exec family of functions present in the standard library, or even more commonly through higher level abstractions such as popen() or system().

It is important to note that when we execute a file through execve() , no new process is generated. Instead, our calling process will mutate into an instance of execution of the new executable. The PID won’t change, but the machine code, data, heap and stack of the process will be replaced inside the kernel space.

This is different to the way we are used to launching executables from the terminal. When we type sleep 30 in the terminal, we get a child process of bash, and the latter does not disappear.

Here another system call is coming into play, the fork() syscall. bash will first create a copy of itself in another child process, and then this child process will call execve() in order to transform itself into sleep. This way bash doesn’t disappear, and will be there to take over control when sleep dies after 30 seconds.

We can skip the forking step through the exec bash bultin

In another terminal we can see that sleep takes over the PID

And sure enough, after 30 seconds when sleep exits there is no bash session, so the terminal window will close.

The kernel side of things

So far we have seen the userspace interacting through syscalls, let’s look at what happens at the other side.

The implementation of those syscalls lives in the kernel. In general lines, the execve() syscall requests the kernel the execution of a certain file in disk, and the kernel needs to load that file into memory where it can be accessed by the CPU.

This is the entry point of the system call, at fs/exec.c

From here, the kernel first performs all required preparations in order to start executing a binary, such as setting up the virtual memory for the process

, and setting the filename, command line arguments, and inherited environment. Yes, environment variables are also first class citizens of the Linux kernel.

Finally, the file “will be executed”.

ELF binaries

Binaries are not only a big blob of machine code. Modern binaries are using the binary ELF format, for Executable and Linkable Format. In simple terms, this is a way of packaging the different code and data sections with some attributes, such as write protection for the .text code section, so that they get mapped into virtual memory for execution. In addition, there are machine independent headers that provide basic information about the executable, such as wether is statically or dynamically linked, the architecture and so on.

The kernel code responsible for parsing the ELF format lives in fs/binfmt_elf.c. Here, the ELF headers are read and analyzed

, and the PT_LOAD sections are loaded into virtual memory

This is just slightly more convoluted for dynamically linked programs. The kernel recognizes a dynamically linked program by the presence of the PT_INTERP header.

This header is hardcoded at compile time with the path of the runtime linker ld-linux-x86-64.so that needs to be used to run it. The runtime linker will find in the filesystem the .so libraries that the binary needs to execute, and will load them into memory.

In this simple case only the standard C library needs to be dynamically linked, because vDSO is a special virtual library put there for efficient execution of read only syscalls.

The kernel will recognize the PT_INTERP header, and will also load the runtime linker (a.k.a ELF interpreter) ld.so and execute it.

Then ld.so will find and load the .so dynamic libraries, or fail if any undefined symbol remains unresolved, and finally will jump execution to the beginning (AT_ENTRY) of the original binary code.

We get the idea that the kernel is the one that inspects the binary and handles it, but in reallity, we are not executing our binary, but the ELF interpreter ld.so instead. Technically it is our binary’s machine code that it is still being executed but we are faced with a concept, the interpreter which is the one that is actually executable, and that is the one actually “interpreting” our file.

At the end of the day, we are doing this

What about scripts?

I have been trying hard to avoid the word binary because you can actually “execute” files that are not binary. These files are technically not executed themselves, because they don’t necessarily contain machine code, but by an interpreter as we just saw.

Now, let’s look at how a executable script is run. I used to imagine that the bash process (or the file manager) inspects the first bytes of the file, and if it finds the shebang, for instance #!/bin/python2 , then it calls the appropriate interpreter. Turns out this is not how it works. The shebang detection actually happens in the Linux Kernel itself.

This means there is more to execution than just ELF: Linux supports a bunch of binary formats, being ELF just one of them. Inside the kernel, each binary format is run by a handler that knows how to deal with said file. There are some handlers that come with the standard kernel, but some others can be added through loadable modules.

Whenever a file is to be executed through execve(), its 128 first bytes are read and passed on to every handler. This occurs at fs/exec.c

Each handler can then accept it or ignore it, usually depending on some magic in the first bytes of the binary. This way, the appropriate handler takes care of the execution of that binary, or passes on the chance of doing so to another handler.

In the case of the ELF format, the magic is 0x7F ‘ELF’ in the field e_ident

This is checked by the ELF handler at binfmt_elf.c in order to accept the binary.

So what happens with scripts? well, it turns out that there is a handler for that in the kernel, that can be found at binfmt_script.c.

All binary format handlers offer an interface to the execve(), for instance this is the one for the ELF format

The main hook here is the load_binary() function that will be different for each handler.

In the case of the script handler, its load_binary() hook is at binfmt_script.c, and starts like this.

So it is the kernel who actually parses the first line of the script, and passes on execution to the interpreter with the script path as an argument. As long as the file starts with the shebang #!, it will be interpreted as a script, be it python, awk, sed, perl, bash, ash, sh, zsh or any similar other.

Once more, we are not actually executing our script, but we are doing something like

We are starting to see that the name binary format is a bit misleading, as we can execute things that are not binaries. There are other handlers for exotic or old binary formats, such as the flat format, or the old a.out format, and in particular there is a very powerful and versatile handler, the binfmt_misc handler.

Execute anything with bitfmt_misc

Now we know what a binary handler is, and we can understand binfmt_misc. This is a flexible format handler that allows us to specify what userland interpreter should run for a specific file type. It doesn’t just look at a hardcoded magic at the beginning of the file, but also supports detecting the binary by extension, using masks, and offers a /proc interface to the system administrator. Remember that all this is happening in kernel space. The loader for this handler is load_misc_binary() at fs/binfmt_misc.c.

If the /proc interface is not already mounted for us, we can do so with

Let’s have a look at it

We can see that we already have it populated with some python and other entries.

We can remove, enable or disable these entries.

- echo 1 to enable entry

- echo 0 to disable entry

- echo -1 to remove entry

What is really cool is that we can easily add custom entries through binfmt_misc. In order to add an entry, you echo a format string to register. Details on how to configure all these flags, masks and magic values can be found here.

As an example, let’s create a handler for the JPG image format to be opened by the feh image viewer. In this case we are matching by extension (therefore the E )

The handler is registered now. We can inspect it

Now let’s take a picture, make executable, et voila.

Let’s now create an executable TODO list, based on magic number detection ( M ).

PDFs start with the text %PDF , as seen in the specification.

Another example, Libreoffice files by extension

We have all the new entries in proc

With this technique we can run transparently Java applications (based on the 0xCAFEBABE magic)

This requires the use of a wrapper, that you can get from the Arch Wiki.

This also works for Mono, and even DOS! In order to run good old Civilization transparently, install dosbox, configure binfmt_misc

Some goes for Windows emulated binaries

The problem is that all DOS, Windows and Mono binaries share the same MZ magic, so in order to combine them, we would need to use a special wrapper that is able to detect the differences deeper in the file, such as start.exe.

If we want to make these settings permanent, we can setup this configuration at boot time at /etc/binfmt.d. For instance, if we wanted to setup the PDF handler at boot time, we just add a new file to the folder

We can see that this approach is very flexible and powerful. One problem with it is that it is a bit unconventional to have “regular files” other than scripts as executable. The good thing about it is that it is truly a system wide setting, so once you set it up in the kernel, it will work from all your shells, file managers and any other user of the execve() system call.

We will see some more useful things we can do with binfmt_misc in the following post.

References

This article aims at being a gentle overview of binfmt_misc and the execution process with some practical examples. If you want the gory details, consider reading the following references.

Источник