- Переменная PATH в Linux

- Переменная PATH в Linux

- Выводы

- How to Set Environment Variables in Linux

- Overview

- Setting an Environment Variable

- Unsetting an Environment Variable

- Listing All Set Environment Variables

- Persisting Environment Variables for a User

- Export Environment Variable

- Setting Permanent Global Environment Variables for All Users

- Conclusion

- Linux environment variable tips and tricks

- Starting with the env command

- More Linux resources

- Exploring shell levels ( SHLVL )

- Manipulating your PATH variable

- Unraveling $USER , $PWD , and $LOGNAME

- Playing the $SHELL game

- Setting your own environment variables

- Wrapping up

- Environment variables

- Contents

- Utilities

- Defining variables

- Globally

- Per user

- Graphical environment

- Per session

- Examples

- Default programs

- Using pam_env

Переменная PATH в Linux

Когда вы запускаете программу из терминала или скрипта, то обычно пишете только имя файла программы. Однако, ОС Linux спроектирована так, что исполняемые и связанные с ними файлы программ распределяются по различным специализированным каталогам. Например, библиотеки устанавливаются в /lib или /usr/lib, конфигурационные файлы в /etc, а исполняемые файлы в /sbin/, /usr/bin или /bin.

Таких местоположений несколько. Откуда операционная система знает где искать требуемую программу или её компонент? Всё просто — для этого используется переменная PATH. Эта переменная позволяет существенно сократить длину набираемых команд в терминале или в скрипте, освобождая от необходимости каждый раз указывать полные пути к требуемым файлам. В этой статье мы разберёмся зачем нужна переменная PATH Linux, а также как добавить к её значению имена своих пользовательских каталогов.

Переменная PATH в Linux

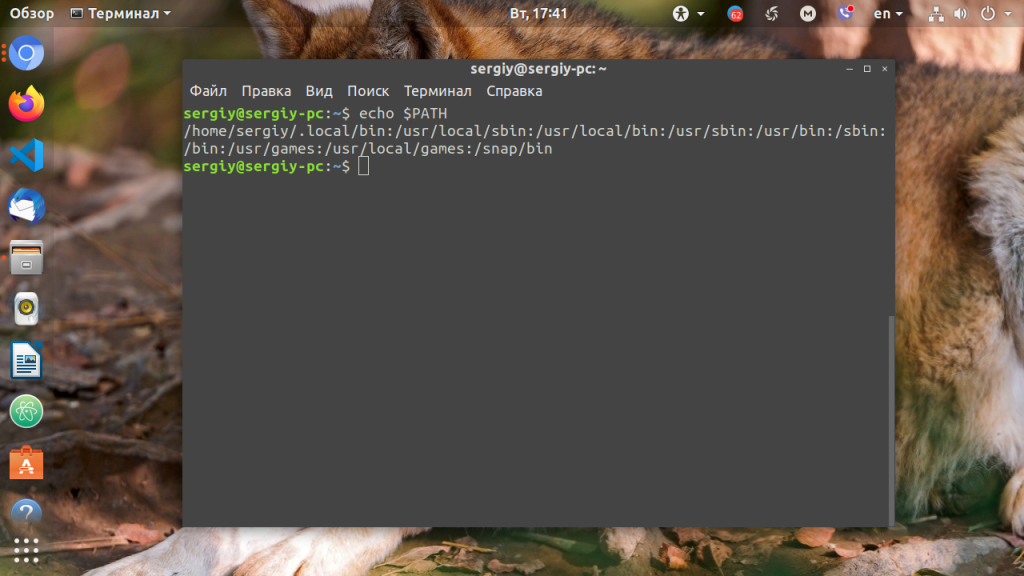

Для того, чтобы посмотреть содержимое переменной PATH в Linux, выполните в терминале команду:

На экране появится перечень папок, разделённых двоеточием. Алгоритм поиска пути к требуемой программе при её запуске довольно прост. Сначала ОС ищет исполняемый файл с заданным именем в текущей папке. Если находит, запускает на выполнение, если нет, проверяет каталоги, перечисленные в переменной PATH, в установленном там порядке. Таким образом, добавив свои папки к содержимому этой переменной, вы добавляете новые места размещения исполняемых и связанных с ними файлов.

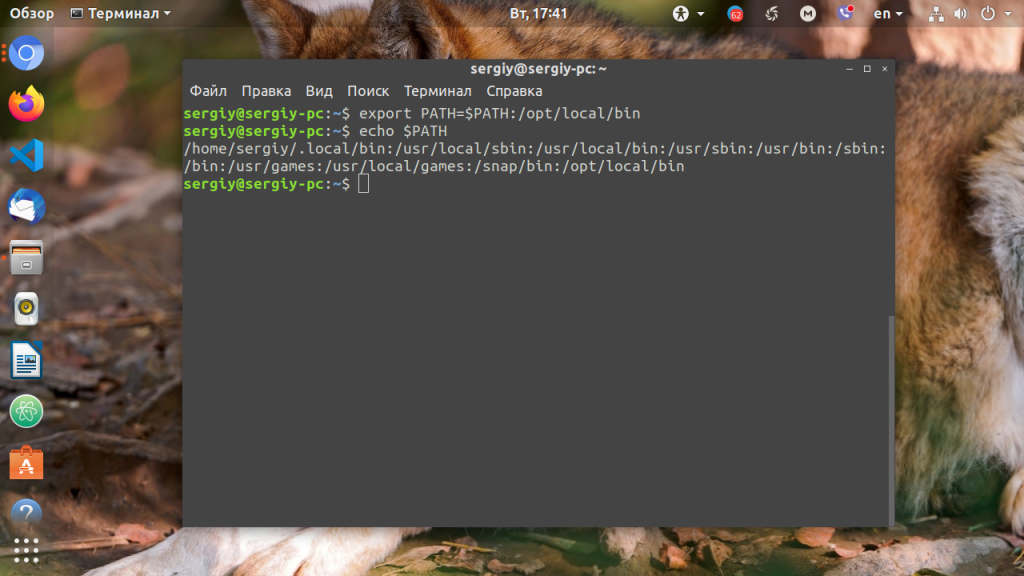

Для того, чтобы добавить новый путь к переменной PATH, можно воспользоваться командой export. Например, давайте добавим к значению переменной PATH папку/opt/local/bin. Для того, чтобы не перезаписать имеющееся значение переменной PATH новым, нужно именно добавить (дописать) это новое значение к уже имеющемуся, не забыв о разделителе-двоеточии:

Теперь мы можем убедиться, что в переменной PATH содержится также и имя этой, добавленной нами, папки:

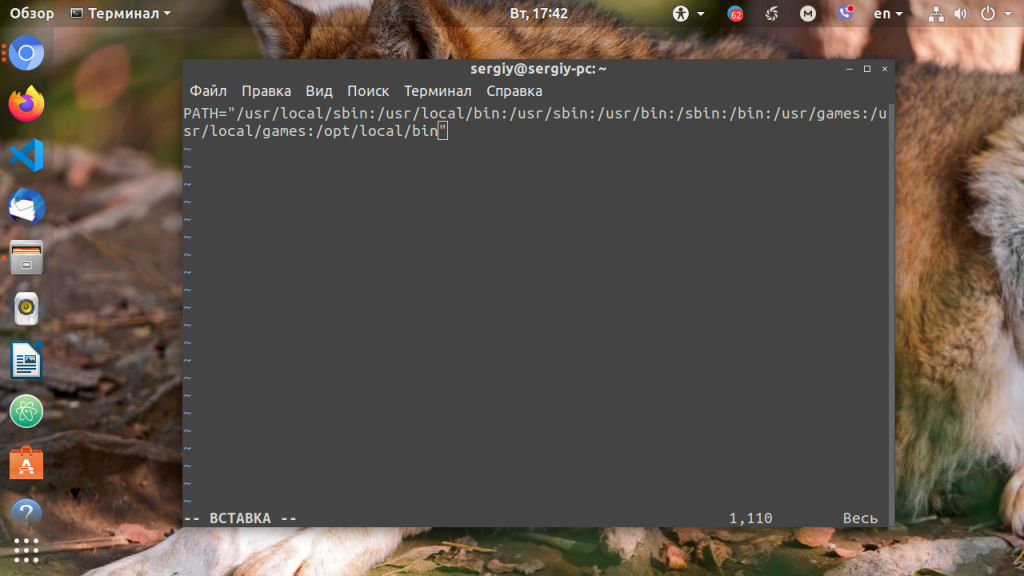

Вы уже знаете как в Linux добавить имя требуемой папки в переменную PATH, но есть одна проблема — после перезагрузки компьютера или открытия нового сеанса терминала все изменения пропадут, ваша переменная PATH будет иметь то же значение, что и раньше. Для того, чтобы этого не произошло, нужно закрепить новое текущее значение переменной PATH в конфигурационном системном файле.

В ОС Ubuntu значение переменной PATH содержится в файле /etc/environment, в некоторых других дистрибутивах её также можно найти и в файле /etc/profile. Вы можете открыть файл /etc/environment и вручную дописать туда нужное значение:

sudo vi /etc/environment

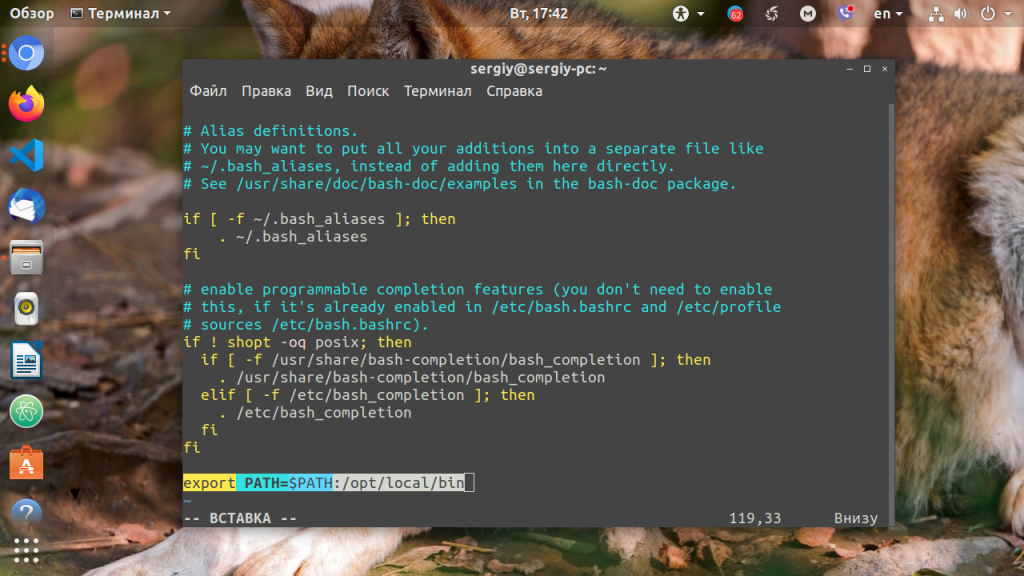

Можно поступить и иначе. Содержимое файла .bashrc выполняется при каждом запуске оболочки Bash. Если добавить в конец файла команду export, то для каждой загружаемой оболочки будет автоматически выполняться добавление имени требуемой папки в переменную PATH, но только для текущего пользователя:

Выводы

В этой статье мы рассмотрели вопрос о том, зачем нужна переменная окружения PATH в Linux и как добавлять к её значению новые пути поиска исполняемых и связанных с ними файлов. Как видите, всё делается достаточно просто. Таким образом вы можете добавить столько папок для поиска и хранения исполняемых файлов, сколько вам требуется.

Источник

How to Set Environment Variables in Linux

Overview

In this tutorial, you will learn how to set environment variables in Ubuntu, CentOS, Red Hat, basically any Linux distribution for a single user and globally for all users. You will also learn how to list all environment variables and how to unset (clear) existing environment variables.

Environment variables are commonly used within the Bash shell. It is also a common means of configuring services and handling web application secrets.

It is not uncommon for environment specific information, such as endpoints and passwords, for example, to be stored as environment variables on a server. They are also used to set the important directory locations for many popular packages, such as JAVA_HOME for Java.

Setting an Environment Variable

To set an environment variable the export command is used. We give the variable a name, which is what is used to access it in shell scripts and configurations and then a value to hold whatever data is needed in the variable.

For example, to set the environment variable for the home directory of a manual OpenJDK 11 installation, we would use something similar to the following.

To output the value of the environment variable from the shell, we use the echo command and prepend the variable’s name with a dollar ($) sign.

And so long as the variable has a value it will be echoed out. If no value is set then an empty line will be displayed instead.

Unsetting an Environment Variable

To unset an environment variable, which removes its existence all together, we use the unset command. Simply replace the environment variable with an empty string will not remove it, and in most cases will likely cause problems with scripts or application expecting a valid value.

To following syntax is used to unset an environment variable

For example, to unset the JAVA_HOME environment variable, we would use the following command.

Listing All Set Environment Variables

To list all environment variables, we simply use the set command without any arguments.

An example of the output would look something similar to the following, which has been truncated for brevity.

Persisting Environment Variables for a User

When an environment variable is set from the shell using the export command, its existence ends when the user’s sessions ends. This is problematic when we need the variable to persist across sessions.

To make an environment persistent for a user’s environment, we export the variable from the user’s profile script.

- Open the current user’s profile into a text editor

- Add the export command for every environment variable you want to persist.

- Save your changes.

Adding the environment variable to a user’s bash profile alone will not export it automatically. However, the variable will be exported the next time the user logs in.

To immediately apply all changes to bash_profile, use the source command.

Export Environment Variable

Export is a built-in shell command for Bash that is used to export an environment variable to allow new child processes to inherit it.

To export a environment variable you run the export command while setting the variable.

We can view a complete list of exported environment variables by running the export command without any arguments.

To view all exported variables in the current shell you use the -p flag with export.

Setting Permanent Global Environment Variables for All Users

A permanent environment variable that persists after a reboot can be created by adding it to the default profile. This profile is loaded by all users on the system, including service accounts.

All global profile settings are stored under /etc/profile. And while this file can be edited directory, it is actually recommended to store global environment variables in a directory named /etc/profile.d, where you will find a list of files that are used to set environment variables for the entire system.

- Create a new file under /etc/profile.d to store the global environment variable(s). The name of the should be contextual so others may understand its purpose. For demonstrations, we will create a permanent environment variable for HTTP_PROXY.

- Open the default profile into a text editor.

- Add new lines to export the environment variables

Conclusion

This tutorial covered how to set and unset environment variables for all Linux distributions, from Debian to Red Hat. You also learned how to set environment variables for a single user, as well as all users.

Источник

Linux environment variable tips and tricks

Environment variables exist to enhance and to standardize your shell environment on Linux systems. There are standard environment variables that the system sets up for you, but you can also set up your own environment variables, or optionally change the default ones to meet your needs.

Starting with the env command

If you want to see your environment variables, use the env command and look for the words in all caps in the output’s far left. These are your environment variables, and their values are to the right:

More Linux resources

I have omitted the output of the LS_COLORS variable because it is so long. Try this command on your system to see what the full output looks like.

Many environment variables are set and then exported from the /etc/profile file and the /etc/bashrc file. There is a line in /etc/profile that reads:

To make permanent changes to the environment variables for all new accounts, go to your /etc/skel files, such as .bashrc , and change the ones that are already there or enter the new ones. When you create new users, these /etc/skel files will be copied to the new user’s home directory.

Exploring shell levels ( SHLVL )

To call the value of a single environment variable, enter the following command, using SHLVL (Shell Level) as an example:

This variable changes depending on how many subshells you have open. For example, enter bash twice and then issue the command again:

A shell level of three means that you are two subshells deep, so type exit twice to return to your regular shell.

[Want to try out Red Hat Enterprise Linux? Download it now for free.]

Manipulating your PATH variable

The PATH variable contains the search path for executing commands and scripts. To see your PATH , enter:

Temporarily change your PATH by entering the following command to add /opt/bin :

The change is temporary for the current session. It isn’t permanent because it’s not entered into the .bashrc file. To make the change permanent, enter the command PATH=$PATH:/opt/bin into your home directory’s .bashrc file.

When you do this, you’re creating a new PATH variable by appending a directory to the current PATH variable, $PATH . A colon ( : ) separates PATH entries.

Unraveling $USER , $PWD , and $LOGNAME

I had a theory that I think has been dispelled by my own good self. My theory was that the commands pwd and whoami probably just read and echoed the contents of the shell variables $PWD and $USER or $LOGNAME , respectively. To my surprise, after looking at the source code, they don’t. Maybe I should rewrite them to do just that. There’s no reason to add multiple libraries and almost 400 lines of C code to display the working directory. You can just read $PWD and echo that to the screen (stdout). The same goes for whoami with either $USER or $LOGNAME .

If you want to have a look at the source code for yourself, it’s on GitHub and other places. If you find that these programs (or others) do use shell variables, I’d love to know about it. Admittedly, I’m not that great at reading C source code, so they could very well use shell variables and I’d never know it. They just didn’t seem to from what I read and could understand.

Playing the $SHELL game

In this last environment variable overview, I want to show you how the $SHELL variable comes in handy. You don’t have to stay in your default shell, which is likely Bash. You can enter into and work in any shell that’s installed on the system. To find out which shells are installed on your system, use the following command:

All of those are actually Bash, so don’t get excited. If you’re lucky, you might also see entries for /bin/tcsh , /bin/csh , /bin/mksh , /bin/ksh , and /bin/rksh .

You can use any of these shells and have different things going on in each one if you’re so inclined. But, let’s say that you’re a Solaris admin and you want to use the Korn shell. You can change your default shell to /bin/ksh using the chsh command:

Now, if you type echo $SHELL , the response will be /bin/bash , so you have to log out and log in again to see the change. Once you log out and log in, you will receive a different response to echo $SHELL .

You can enter other shells and echo $SHELL should report your current shell and $SHLVL , which will keep you oriented as to how many shells deep you are.

Setting your own environment variables

You can set your own variables at the command line per session, or make them permanent by placing them into the

/.profile , or whichever startup file you use for your default shell. On the command line, enter your environment variable and its value as you did earlier when changing the PATH variable.

Wrapping up

Shell or environment variables are helpful to users, sysadmins, and programmers alike. They are useful on the command line and in scripts. I’ve used them over the years for many different purposes, and although some of them are probably a little unconventional, they worked and still do. Create your own or use the ones given to you by the system and installed applications. They truly can enrich your Linux user experience.

As a side note on variables and shells, does anyone think that those who program in JSON should only be allowed to use the Bourne Shell? Discuss.

Источник

Environment variables

An environment variable is a named object that contains data used by one or more applications. In simple terms, it is a variable with a name and a value. The value of an environmental variable can for example be the location of all executable files in the file system, the default editor that should be used, or the system locale settings. Users new to Linux may often find this way of managing settings a bit unmanageable. However, environment variables provide a simple way to share configuration settings between multiple applications and processes in Linux.

Contents

Utilities

The coreutils package contains the programs printenv and env. To list the current environmental variables with values:

The env utility can be used to run a command under a modified environment. The following example will launch xterm with the environment variable EDITOR set to vim . This will not affect the global environment variable EDITOR .

The Bash builtin set allows you to change the values of shell options and set the positional parameters, or to display the names and values of shell variables. For more information, see the set builtin documentation.

Each process stores their environment in the /proc/$PID/environ file. This file contains each key value pair delimited by a nul character ( \x0 ). A more human readable format can be obtained with sed, e.g. sed ‘s:\x0:\n:g’ /proc/$PID/environ .

Defining variables

Globally

Most Linux distributions tell you to change or add environment variable definitions in /etc/profile or other locations. Keep in mind that there are also package-specific configuration files containing variable settings such as /etc/locale.conf . Be sure to maintain and manage the environment variables and pay attention to the numerous files that can contain environment variables. In principle, any shell script can be used for initializing environmental variables, but following traditional UNIX conventions, these statements should only be present in some particular files.

The following files should be used for defining global environment variables on your system: /etc/environment , /etc/profile and shell specific configuration files. Each of these files has different limitations, so you should carefully select the appropriate one for your purposes.

- /etc/environment is used by the pam_env module and is shell agnostic so scripting or glob expansion cannot be used. The file only accepts variable=value pairs. See pam_env(8) and pam_env.conf(5) for details.

- /etc/profile initializes variables for login shells only. It does, however, run scripts and can be used by all Bourne shell compatible shells.

- Shell specific configuration files — Global configuration files of your shell, initializes variables and runs scripts. For example Bash#Configuration files or Zsh#Startup/Shutdown files.

In this example, we add

/bin directory to the PATH for respective user. To do this, just put this in your preferred global environment variable config file ( /etc/profile or /etc/bash.bashrc ):

Per user

You do not always want to define an environment variable globally. For instance, you might want to add /home/my_user/bin to the PATH variable but do not want all other users on your system to have that in their PATH too. Local environment variables can be defined in many different files:

/.pam_environment is the user specific equivalent of /etc/security/pam_env.conf [1], used by pam_env module. See pam_env(8) and pam_env.conf(5) for details.

To add a directory to the PATH for local usage, put following in

To update the variable, re-login or source the file: $ source

/.bashrc etc. This means that, for example, dbus activated programs like Gnome Files will not use them by default. See Systemd/User#Environment variables.

Reading

/.pam_environment is deprecated and the feature will be removed at some point in the future.

Graphical environment

Environment variables for Xorg applications can be set in xinitrc, or in xprofile when using a display manager, for example:

/.config/environment.d/ on Wayland sessions is GDM-specific behavior. (Discuss in Talk:Environment variables)

Applications running on Wayland may use systemd user environment variables instead, as Wayland does not initiate any Xorg related files:

To set environment variables only for a specific application instead of the whole session, edit the application’s .desktop file. See Desktop entries#Modify environment variables for instructions.

Per session

Sometimes even stricter definitions are required. One might want to temporarily run executables from a specific directory created without having to type the absolute path to each one, or editing shell configuration files for the short time needed to run them.

In this case, you can define the PATH variable in your current session, combined with the export command. As long as you do not log out, the PATH variable will be using the temporary settings. To add a session-specific directory to PATH , issue:

Examples

The following section lists a number of common environment variables used by a Linux system and describes their values.

- DE indicates the Desktop Environment being used. xdg-open will use it to choose more user-friendly file-opener application that desktop environment provides. Some packages need to be installed to use this feature. For GNOME, that would be libgnomeAUR ; for Xfce this is exo . Recognised values of DE variable are: gnome , kde , xfce , lxde and mate .

The DE environment variable needs to be exported before starting the window manager. For example: This will make xdg-open use the more user-friendly exo-open, because it assumes it is running inside Xfce. Use exo-preferred-applications for configuring.

- DESKTOP_SESSION is similar to DE , but used in LXDE desktop environment: when DESKTOP_SESSION is set to LXDE , xdg-open will use PCManFM file associations.

- PATH contains a colon-separated list of directories in which your system looks for executable files. When a regular command (e.g. ls, systemctl or pacman) is interpreted by the shell (e.g. bash or zsh), the shell looks for an executable file with the same name as your command in the listed directories, and executes it. To run executables that are not listed in PATH , a relative or absolute path to the executable must be given, e.g. ./a.out or /bin/ls .

- HOME contains the path to the home directory of the current user. This variable can be used by applications to associate configuration files and such like with the user running it.

- PWD contains the path to your working directory.

- OLDPWD contains the path to your previous working directory, that is, the value of PWD before last cd was executed.

- TERM contains the type of the running terminal, e.g. xterm-256color . It is used by programs running in the terminal that wish to use terminal-specific capabilities.

- MAIL contains the location of incoming email. The traditional setting is /var/spool/mail/$LOGNAME .

- ftp_proxy and http_proxy contains FTP and HTTP proxy server, respectively:

- MANPATH contains a colon-separated list of directories in which man searches for the man pages.

- INFODIR contains a colon-separated list of directories in which the info command searches for the info pages, e.g., /usr/share/info:/usr/local/share/info

- TZ can be used to to set a time zone different to the system zone for a user. The zones listed in /usr/share/zoneinfo/ can be used as reference, for example TZ=»:/usr/share/zoneinfo/Pacific/Fiji» . When pointing the TZ variable to a zoneinfo file, it should start with a colon per the GNU manual.

Default programs

- SHELL contains the path to the user’s preferred shell. Note that this is not necessarily the shell that is currently running, although Bash sets this variable on startup.

- PAGER contains command to run the program used to list the contents of files, e.g., /bin/less .

- EDITOR contains the command to run the lightweight program used for editing files, e.g., /usr/bin/nano . For example, you can write an interactive switch between gedit under X or nano, in this example:

- VISUAL contains command to run the full-fledged editor that is used for more demanding tasks, such as editing mail (e.g., vi , vim, emacs etc).

- BROWSER contains the path to the web browser. Helpful to set in an interactive shell configuration file so that it may be dynamically altered depending on the availability of a graphic environment, such as X:

Using pam_env

The PAM module pam_env(8) loads the variables to be set in the environment from the following files: /etc/security/pam_env.conf , /etc/environment and

- /etc/environment must consist of simple VARIABLE=value pairs on separate lines, for example:

- /etc/security/pam_env.conf and

/.pam_environment share the same following format: @

Источник