- Navigating your filesystem in the Linux terminal

- More Linux resources

- View file lists

- Open a folder

- Close a folder

- Navigate directories

- Absolute paths

- Conclusion

- A beginner’s guide to navigating the Linux filesystem

- The basics

- More Linux resources

- Print working directory ( pwd )

- Change directory ( cd )

- Wrapping up

Navigating your filesystem in the Linux terminal

More Linux resources

You probably learned how to interact with a computer using a GUI, and you’re probably very good at it. You may be surprised to learn, then, that there’s a more direct way to use a computer: a terminal, or shell, which provides a direct interface between you and the operating system. Because of this direct communication without the intervention of additional applications, using a terminal also makes it easy to script repetitive tasks, and design workflows unique to your own needs.

There’s a catch, however. As with any new tool, you have to learn the shell before you can do anything useful with it.

This article compares navigating a computer desktop without the desktop. That is, this article demonstrates how to use a terminal to move around and browse your computer as you would on a desktop, but from a terminal instead.

While the terminal may seem mysterious and intimidating at first, it’s easy to learn once you realize that a terminal uses the same information as all of your usual applications. There are direct analogs for everything you do in a GUI to most of the everyday activities you do in a terminal. So instead of starting your journey with the shell by learning terminal commands, begin with everyday tasks that you’re already familiar with.

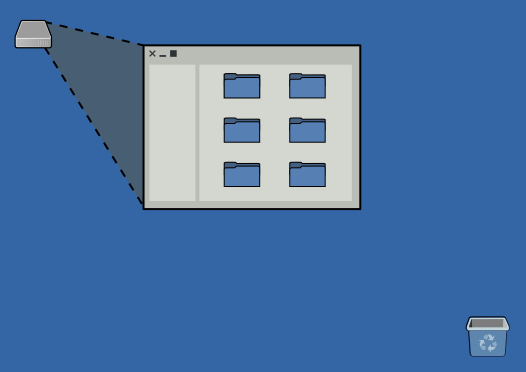

View file lists

The pwd (print working directory) command tells you what directory you’re currently in. From there, the ls (list) command shows you what’s in that (or any other) directory:

The first items listed are dots. The single dot is a meta-location, meaning the folder you are currently in.

The double dot is an indicator that you can move back from this location. That is, you’re in a folder inside of another folder. Once you start moving around within your computer, you can use that information for reference.

You may also notice that it’s hard to tell a file from a folder. Some Linux distributions have colors pre-programmed so that folders are blue, files are white, binary files are green, and so on. If you don’t see those colors, you can use ls —color to try and activate that feature. Colors don’t always transmit over remote connections to distant servers, though, so a common and generic method to make it clear what are files and what are folders is the —classify ( -F ) switch:

Folders are given a trailing slash ( / ) to denote that they are directories. Binary entities, like ZIP files and executable programs, are indicated with an asterisk ( * ). Plain text files are listed without additional notation.

If you’re used to the dir command from Windows, you can use that on Linux as well. It works exactly the same as ls .

Open a folder

To open—or enter—a folder on the command line, use the cd (change directory) command as follows:

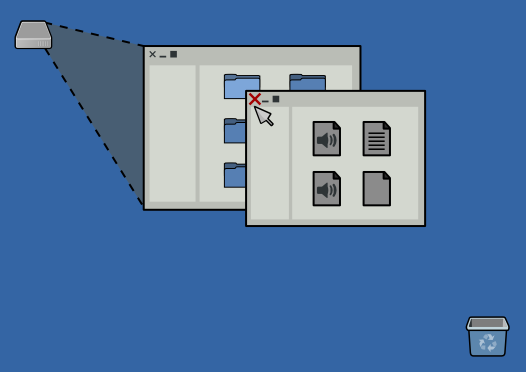

Close a folder

On a desktop, you judge your current location by what window you have open. For instance, when you open a window and click on the Documents folder icon, you think of yourself as being in your Documents folder.

In a terminal, the closest thing to this concept is the shell prompt. In most shells, your prompt is a dollar sign ( $ ), and its location within the computer can change depending on where you tell your terminal to go. You can always learn your current location with the pwd (print working directory) command:

If you’re in one location because you used the cd command, you can «close» that location by going back to your home directory. This directory is, more or less, your terminal’s desktop—it’s the place you find yourself staring at when you first open the terminal.

The command for returning home is the cd command with no location specified (shorthand for cd

Navigate directories

Navigating a Linux computer is like navigating the internet. The very concept of a URL is pulled directly from UNIX. When you navigate to a specific page on a website, like https://www.redhat.com/en/topics/linux, you’re actually changing directory to /var/www/redhat.com/en/topics/linux (this isn’t exactly true for pages built by PHP and other dynamic languages, but even they are essentially building a virtual file system).

To go back a page in this example, delete the linux part of the URL. You’re taken to a new location, the parent directory, containing a different file for you to view. Because this happens inside your web browser, you probably don’t think of it as navigating a computer, but you use the same principle in a Linux terminal.

Think of your computer as the internet (or the internet as a computer, more appropriately). If you start in your home folder, then all of your personal files can be expressed using your home as the starting point. Think of your home folder as a web URL’s domain. Instead of a URL, the term directory path or file path is used. Here are some example paths:

- /home/seth/bin

- /home/seth/despacer.sh

- /home/seth/documentation.zip*

- /home/seth/people

Because you return home often, your home directory can be abbreviated as

To navigate directly to the people folder, use the cd command along with the entire directory path:

Suppose that inside the people folder, there are the directories developers and marketing .

Now that you’re inside the people directory, you can move out of it in one of three different ways.

One option is to navigate into a different directory from where you are now. This method uses a dot as your starting point.

Remember that a dot is a meta-location, meaning «where I am right now.» This method is akin to, for instance, manually adding a level in a URL, such as changing https://www.redhat.com/en/topics to https://www.redhat.com/en/topics/linux. So, to change to the developers directory from your current location, do the following:

You could move through all of your directories this way: change directory to one folder, list its contents, and then move into the next one, and so on. However, if you know the path of where you want to go, you can transport yourself there instantly all in one command. To reach the to /home/seth/people/developers directory instantly from anywhere, instantly:

Once in a directory, you always have the option to backtrack out of your current location using the meta-location .. to tell cd to take you up one folder:

You can keep using this trick until you have nowhere left to go:

You can also always return to your home directory instantly using this shortcut:

Because users go home often, most shells are set to go back home should you type cd with no destination:

Absolute paths

File paths technically start at the very root of your computer’s file tree. Even your home directory starts at the very bottom of the tree. This fact is significant because system administrators deal with lots of data that exists outside of their own home directory.

When you go as far back in a file path you can go, you reach the root directory, represented by a single slash ( / ). You see the root directory at the beginning of all absolute paths:

When in doubt, you can always use the absolute path to any location:

To find where you want to go, use the ls command to «open» a directory and look inside:

Conclusion

Try navigating through your system using the terminal. As long as you restrict yourself to the cd , ls , and pwd commands, you can’t do any harm, and the practice will help you get comfortable with the process. On most systems, the Tab key auto-completes file paths as you type, so if you’re changing to

/people/marketing , then all you need to type is cd

/people/m and then press Tab. If Tab is unable to complete the path, you know that you either have the wrong path or there are several directories with similar names, so your shell is unable to choose which to use for auto-completion.

Navigating in the terminal takes practice, but it is far faster than opening and closing windows, and clicking on Back buttons and folder icons, especially when you already know where you want to go. Give it a try!

Источник

A beginner’s guide to navigating the Linux filesystem

Photo by Ylanite Koppens from Pexels

The basics

More Linux resources

Before we get into commands, let’s talk about important special characters. The dot ( . ) , dot-dot ( .. ) , forward slash ( / ), and tilde (

), all have special functionality in the Linux filesystem:

- The dot ( . ) represents the current directory in the filesystem.

- The dot-dot ( .. ) represents one level above the current directory.

- The forward slash ( / ) represents the «root» of the filesystem. (Every directory/file in the Linux filesystem is nested under the root / directory.)

- The tilde (

) represents the home directory of the currently logged in user.

I believe that the best way to understand any concept is by putting it into practice. This navigation command overview will help you to better understand how all of this works.

Print working directory ( pwd )

The pwd command prints the current/working directory, telling where you are currently located in the filesystem. This command comes to your rescue when you get lost in the filesystem, and always prints out the absolute path.

What is an absolute path? An absolute path is the full path to a file or directory. It is relative to the root directory ( / ). Note that it is a best practice to use absolute paths when you use file paths inside of scripts. For example, the absolute path to the ls command is: /usr/bin/ls .

If it’s not absolute, then it’s a relative path. The relative path is relative to your present working directory. If you are in your home directory, for example, the ls command’s relative path is: . ./../usr/bin/ls .

Change directory ( cd )

The cd command lets you change to a different directory. When you log into a Linux machine or fire up a terminal emulator, by default your working directory is your home directory. My home directory is /home/kc . In your case, it is probably /home/ .

Absolute and relative paths make more sense when we look at examples for the cd command. If you need to move one level up from your working directory, in this case /home , we can do this couple of ways. One way is to issue a cd command relative to your pwd :

Note: Remember, .. represents the directory one level above the working directory.

The other way is to provide the absolute path to the directory:

Either way, we are now inside /home . You can verify this by issuing pwd command. Then, you can move to the filesystem’s root ( / ) by issuing this command:

If your working directory is deeply nested inside the filesystem and you need to return to your home directory, this is where the

comes in with the cd command. Let’s put this into action and see how cool this command can be. It helps you save a ton of time while navigating in the filesystem.

My present working directory is root ( / ). If you’re following along, yours should be same, or you can find out yours by issuing pwd . Let’s cd to another directory:

To navigate back to your home directory, simply issue

with the cd command:

Again, check your present working directory with the pwd command:

The dash ( — ) navigates back to the previous working directory, similar to how you can navigate to your user home directory with

. If you need to go back to our deeply nested directory 9 under your user home directory (this was my previous working directory), you would issue this command:

Wrapping up

These commands are your navigation tools inside the Linux filesystem. With what you learned here, you can always find your way to the home (

) directory. If you want to learn more and master the command line, check out 10 basic Linux commands.

Want to try out Red Hat Enterprise Linux? Download it now for free.

Источник