- Is windows big endian

- Answered by:

- Question

- Answers

- Понятие порядка байтов в цифровых системах: прямой (Big Endian) и обратный (Little Endian) порядок байтов

- Что такое порядок байтов?

- Зачем нам нужен порядок байтов

- Порядок байтов в памяти

- Прямой порядок против обратного порядка

- Заключение

- Is x86-64 machine language big endian?

- 2 Answers 2

- What makes a system little-endian or big-endian?

- Question 1

- Question 2

- Question 3

- 6 Answers 6

Is windows big endian

This forum has migrated to Microsoft Q&A. Visit Microsoft Q&A to post new questions.

Answered by:

Question

I wrote a very basic program that will allow me to see the value of each byte in a short variable. But when i run it, the results are backwards (big endian).

instead of 0 255 as my output, i am getting 255 zero.

Im very confused, can anyone help me?

Answers

On 7/8/2011 9:45 AM, CodeDuyvil wrote:

I wrote a very basic program that will allow me to see the value of each byte in a short variable. But when i run it, the results are backwards (big endian).

instead of 0 255 as my output, i am getting 255 zero.

This code doesn’t depend on endianness at all. Regardless of how integers are stored in memory, 0xFF always corresponds to the eight least-significant bits, and operator >> always shifts towards least-signficant bits.

0xFF is just another way of writing 255, so of course 255 & 255 == 255 (and in general, for any integer x, x & x == x). Similarly, (d >> 8) is just another way of writing (d / 256), and 255/256==0.

Endianness is not about the mathematical value of arithmetic operations, but about the layout in memory, so you need to test it as such:

Понятие порядка байтов в цифровых системах: прямой (Big Endian) и обратный (Little Endian) порядок байтов

Различные термины «порядка байтов» («endian») могут показаться немного странными, но основная концепция довольно проста. Если вы еще не хорошо знакомы с вариантами порядка байтов, читайте статью дальше!

Порядок байтов, прямой порядок (big endian), обратный порядок (little endian). Что означают эти термины, и как они влияют на работу инженеров?

Что такое порядок байтов?

Оказывает, это неправильный вопрос. При обсуждении данных «порядок байтов» не является отдельным термином. Вернее, к форматам расположения байтов относятся термины «прямой порядок» («big-endian») и «обратный порядок» («little-endian»).

Термины берут начало в «Путешествиях Гулливера» Джонатана Свифта, в которых начинается гражданская война между теми, кто предпочитает разбивать вареные яйца на большом конце («big-endians»), и теми, кто предпочитает разбивать их на маленьком конце («little-endians»).

В 1980 году израильский ученый-компьютерщик Денни Коэн написал статью («О священных войнах и призыве к миру»), в которой он представил насмешливое объяснение столь же мелкой «войны», вызванной одним вопросом:

«Каков правильный порядок байтов в сообщениях?»

Чтобы объяснить эту проблему, он позаимствовал у Свифта термины «big endian» и «little endian», чтобы описать две противоположные стороны дискуссии о том, что он называл «endianness» (в данном контексте «порядок байтов»).

Когда Свифт писал «Путешествия Гулливера» где-то в первой четверти восемнадцатого века, он, конечно, не знал, что однажды его работа послужит вдохновением для неологизмов двадцатого века, которые определяют расположение цифровых данных в памяти и системах связи. Но такова жизнь – часто странная и всегда непредсказуемая.

Зачем нам нужен порядок байтов

Несмотря на сатирическую трактовку Коэном борьбы «big endians» (прямого порядка, от старшего к младшему) против «little endians» (обратного порядка, от младшего к старшему), вопрос о порядке байтов на самом деле очень важен для нашей работы с данными.

Блок цифровой информации – это последовательность единиц и нулей. Эти единицы и нули начинаются с наименьшего значащего бита (least significant bit, LSb – обратите на строчную букву «b») и заканчиваются на наибольшем значащем бите (most significant bit, MSb).

Это кажется достаточно простым; рассмотрим следующий гипотетический сценарий.

32-разрядный процессор готов к сохранению данных и, следовательно, передает 32 бита данных в соответствующие 32 блока памяти. Этим 32 блокам памяти совместно назначается адрес, скажем 0x01. Шина данных в системе спроектирована таким образом, что нет возможности смешивать LSb с MSb, и все операции используют 32-битные данные, даже если соответствующие числа могут быть легко представлены в 16 или даже 8 битами. Когда процессору требуется получить доступ к сохраненным данным, он просто считывает 32 бита с адреса памяти 0x01. Эта система является надежной, и нет необходимости вводить понятие порядка байтов.

Возможно, вы заметили, что слово «байт» в описании этого гипотетического процессора нигде не упоминалось. Всё основано на 32-битных данных – зачем нужно делить эти данные на 8-битные части, если всё оборудование предназначено для обработки 32-битных данных? Вот здесь-то теория и реальность расходятся. Реальные цифровые системы, даже те, которые могут напрямую обрабатывать 32-битные или 64-битные данные, широко использую 8-битный сегмент данных, известный как байт.

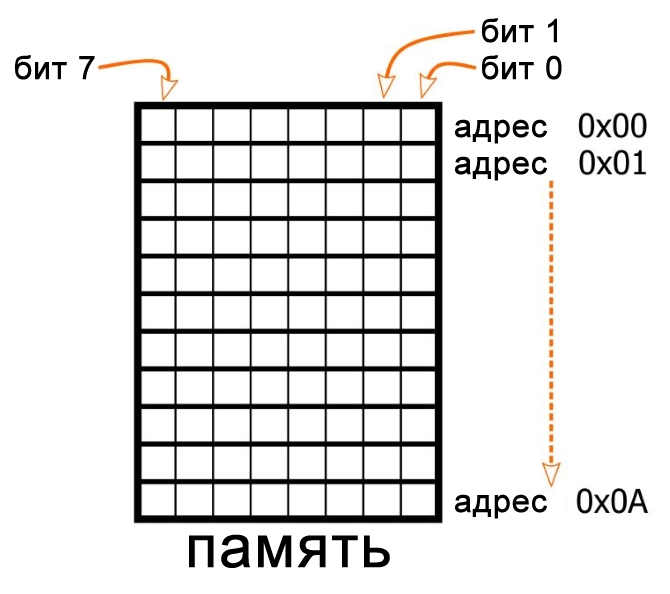

Порядок байтов в памяти

Удобным средством демонстрации порядка байтов действии и объяснения разницы между прямым и обратным порядками является процесс хранения цифровых данных. Представьте, что мы используем 8-разрядный микроконтроллер. Всё аппаратное обеспечение в этом устройстве, включая ячейки памяти, предназначено для 8-битных данных. Таким образом, адрес 0x00 может хранить один байт, адрес 0x01 тоже хранит один байт, и так далее.

Допустим, мы решили запрограммировать этот микроконтроллер, используя компилятор C, который позволяет нам определять 32-разрядные (т.е. 4-байтовые) переменные. Компилятор должен хранить эти переменные в смежных ячейках памяти, но что не очень понятно, так это то, в самом младшем адресе памяти должен храниться наибольший значащий байт (most significant byte, MSB – обратите внимание на заглавную «B») или наименьший значащий байт (least significant byte, LSB).

Другими словами, должна ли система использовать порядок памяти от старшего к младшему (прямой порядок, big-endian) или от младшего к старшему (обратный порядок, little-endian)?

Здесь на самом деле нет правильного или неправильного ответа – любая договоренность может быть совершенно эффективной. Решение между прямым и обратным порядком может быть основано, например, на поддержании совместимости с предыдущими версиями данного процессора, что, конечно, поднимает вопрос о том, как инженеры приняли решение для первого процессора в этом семействе. Я не знаю; возможно, генеральный директор подбросил монету.

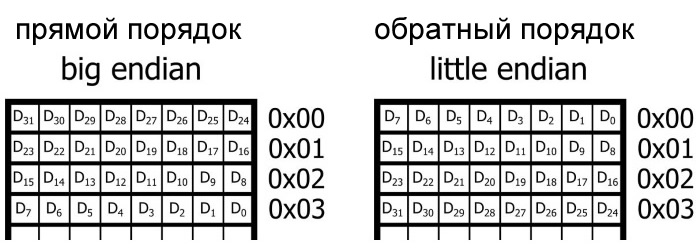

Прямой порядок против обратного порядка

Прямой порядок (big endian) указывает на организацию цифровых данных, которая начинается с «большого» конца слова данных и продолжается в направлении «маленького» конца, где «большой» и «маленький» соответствуют наибольшему значащему и наименьшему значащему битам соответственно.

Обратный порядок (little endian) указывает на организацию, которая начинается с «маленького» конца и продолжается в направлении «большого» конца.

Решение между прямым и обратным порядками байтов не ограничивается схемами памяти и 8-разрядными процессорами. Байт является универсальной единицей в цифровых системах. Подумайте только о персональных компьютерах: пространство на жестком диске измеряется в байтах, ОЗУ измеряется в байтах, скорость передачи данных по USB указывается в байтах в секунду (или в битах в секунду), и это несмотря на тот факт, что 8-разрядные персональные компьютеры полностью устарели. Вопрос о порядке байтов вступает в игру всякий раз, когда цифровая система совмещает хранение или передачу данных на основе байтов с числовыми значениями, длина которых превышает 8 бит.

Инженеры должны знать о порядке байтов, когда данные хранятся, передаются или интерпретируются. Последовательная связь особенно восприимчива к проблемам с порядком байтов, поскольку байты, содержащиеся в многобайтовом слове данных, неизбежно будут передаваться последовательно, обычно либо от MSB до LSB, либо от LSB до MSB.

Параллельные шины не защищены от путаницы с порядком байтов, поскольку ширина шины может быть короче ширины данных. И в этом случае прямой или обратный порядок байтов должен быть выбран для параллельной побайтовой передачи данных.

Примером интерпретации на основе порядка байтов является случай, когда байты данных передаются от модуля датчика на ПК через «последовательный порт» (что в настоящее время почти наверняка означает, что в качестве COM порта используется USB соединение). Допустим, всё, что вам нужно сделать, это вывести эти данные, используя какой-то код MATLAB. Когда вы вводите эти байты в среду MATLAB и конвертируете их в обычные переменные, вы должны интерпретировать значения отдельных байтов в соответствии с порядком, в котором они хранятся в памяти.

Заключение

Очень жаль, что универсальная система порядка байтов не была создана еще в начале цифровой эпохи. Я даже не хочу знать, сколько коллективных часов человеческой жизни было посвящено решению проблем, вызванных несовпадающим порядком байтов.

В любом случае, мы не можем изменить прошлое, и мы также вряд ли убедим каждую компанию, производящую полупроводниковую технику и программное обеспечение, пересмотреть свои производственные линии для достижения единого универсального порядка байтов. Что мы можем сделать, так это добиваться согласованности наших собственных проектов и предоставлять четкую документацию, если существует вероятность конфликта между двумя составляющими частями системы.

Is x86-64 machine language big endian?

I think shows the machine code is big-endian. Is my conclusion right?

2 Answers 2

First, you need to know that the smallest data unit that nearly all modern CPUs can manipulate is a byte, which is 8 bits. For numbers, we (human beings) write and read from left to right and we write the most significant digit first, so the most significant digit is on the left.

Little-endian byte order implies two things for the CPU:

Suppose that the CPU fetches 4 bytes from the memory, e.g. starting at address 0x00 , and that:

- address 0x00 holds the byte 11111111 , which is 0xFF ;

- address 0x01 holds the byte 00111100 , which is 0x3C ;

- address 0x02 holds the byte 00011000 , which is 0x18 ;

- address 0x03 holds the byte 00000000 , which is 0x00 .

Then, when the CPU interprets these 4 bytes as an integer, it will interpret them as the integer value 0x00183CFF . That is, the CPU will consider the byte at the highest address as the Most Significant Byte (MSB). That means, for the CPU, the higher the address is, the more significant the byte on that address is.

- The same thing applies when the CPU writes an integer value like 0x00183CFF to the memory. It will put 0xFF at the lowest address, and 0x00 at the highest address. If you (human being) read bytes intuitively from low addresses to high addresses, you read out FF 3C 18 00 , which byte-for-byte is in the reverse order to how 0x00183CFF is written.

For BIG-endianness, the CPU reads and writes MSBs at lower addresses and LSBs at higher addresses.

What makes a system little-endian or big-endian?

I’m confused with the byte order of a system/cpu/program.

So I must ask some questions to make my mind clear.

Question 1

If I only use type char in my C++ program:

Then compile this program to a executable binary file called a.out .

Can a.out both run on little-endian and big-endian systems?

Question 2

If my Windows XP system is little-endian, can I install a big-endian Linux system in VMWare/VirtualBox? What makes a system little-endian or big-endian?

Question 3

If I want to write a byte-order-independent C++ program, what do I need to take into account?

6 Answers 6

Can a.out both run on little-endian and big-endian system?

No, because pretty much any two CPUs that are so different as to have different endian-ness will not run the same instruction set. C++ isn’t Java; you don’t compile to something that gets compiled or interpreted. You compile to the assembly for a specific CPU. And endian-ness is part of the CPU.

But that’s outside of endian issues. You can compile that program for different CPUs and those executables will work fine on their respective CPUs.

What makes a system little-endian or big-endian?

As far as C or C++ is concerned, the CPU. Different processing units in a computer can actually have different endians (the GPU could be big-endian while the CPU is little endian), but that’s somewhat uncommon.

If I want to write a byte-order independent C++ program, what do I need to take into account?

As long as you play by the rules of C or C++, you don’t have to care about endian issues.

Of course, you also won’t be able to load files directly into POD structs. Or read a series of bytes, pretend it is a series of unsigned shorts, and then process it as a UTF-16-encoded string. All of those things step into the realm of implementation-defined behavior.

There’s a difference between «undefined» and «implementation-defined» behavior. When the C and C++ spec say something is «undefined», it basically means all manner of brokenness can ensue. If you keep doing it, (and your program doesn’t crash) you could get inconsistent results. When it says that something is defined by the implementation, you will get consistent results for that implementation.

If you compile for x86 in VC2010, what happens when you pretend a byte array is an unsigned short array (ie: unsigned char *byteArray = . ; unsigned short *usArray = (unsigned short*)byteArray ) is defined by the implementation. When compiling for big-endian CPUs, you’ll get a different answer than when compiling for little-endian CPUs.

In general, endian issues are things you can localize to input/output systems. Networking, file reading, etc. They should be taken care of in the extremities of your codebase.

Question 1:

Can a.out both run on little-endian and big-endian system?

No. Because a.out is already compiled for whatever architecture it is targeting. It will not run on another architecture that it is incompatible with.

However, the source code for that simple program has nothing that could possibly break on different endian machines.

So yes it (the source) will work properly. (well. aside from void main() , which you should be using int main() instead)

Question 2:

If my WindowsXP system is little-endian, can I install a big-endian Linux system in VMWare/VirtualBox?

Endian-ness is determined by the hardware, not the OS. So whatever (native) VM you install on it, will be the same endian as the host. (since x86 is all little-endian)

What makes a system little-endian or big-endian?

Here’s an example of something that will behave differently on little vs. big-endian:

*Note that this violates strict-aliasing, and is only for demonstration purposes.

On little-endian, the lower bits of a are stored at the lowest address. So when you access a as a 32-bit integer, you will read the lower 32 bits of it. On big-endian, you will read the upper 32 bits.

Question 3:

If I want to write a byte-order independent C++ program, what do I need to take into account?

Just follow the standard C++ rules and don’t do anything ugly like the example I’ve shown above. Avoid undefined behavior, avoid type-punning.

Little-endian / big-endian is a property of hardware. In general, binary code compiled for one hardware cannot run on another hardware, except in a virtualization environments that interpret machine code, and emulate the target hardware for it. There are bi-endian CPUs (e.g. ARM, IA-64) that feature a switch to change endianness.

As far as byte-order-independent programming goes, the only case when you really need to do it is to deal with networking. There are functions such as ntohl and htonl to help you converting your hardware’s byte order to network’s byte order.

The first thing to clarify is that endianness is a hardware attribute, not a software/OS attribute, so WinXP and Linux are not big-endian or little endian, but rather the hardware on which they run is either big-endian or little endian.

Endianness is a description of the order in which the bytes are stored in a data-type. A system that is big-endian stores the most significant (read biggest value) value first and a little-endian system stores the least significant byte first. It is not mandatory to have each datatype be the same as the others on a system so you can have mixed-endian systems.

A program that is little endian would not run on a big-endian system, but that has more to with the instruction set available than the endianness of the system on which it was compiled.

If you want to write a byte-order independent program you simply need to not depend on the byte order of your data.

1: The output of the compiler will depend on the options you give it and if you use a cross-compiler. By default, it should run on the operating system you are compiling it on and not others (perhaps not even others of the same type; not all Linux binaries run on all Linux installs, for example). In large projects, this will be the least of your concern, as libraries, etc, will need built and linked differently on each system. Using a proper build system (like make) will take care of most of this without you needing to worry.

2: Virtual machines abstract the hardware in such a way as to allow essentially anything to run within anything else. How the operating systems manage their memory is unimportant as long as they both run on the same hardware and support whatever virtualization model is in use. Endianness means the byte-order; if it is read left-right or right-left (or some other format). Some hardware supports both and virtualization allows both to coexist in that case (although I am not aware of how this would be useful except that it is possible in theory). However, Linux works on many different architectures (and Windows some other than Ixxx), so the situation is more complicated.

3: If you monkey with raw memory, such as with binary operators, you might put yourself in a position of depending on endianness. However, most modern programming is at a higher level than this. As such, you are likely to notice if you get into something which may impose endianness-based limitations. If such is ever required, you can always implement options for both endiannesses using the preprocessor.