- Chown Command: Change Owner of File in Linux

- Linux Chown Command Syntax

- How to Check Ownership of a File in Linux

- How to Change the Owner of a File

- Change the Owner of a File With UID

- Change Ownership of Multiple Linux Files

- How to Change the Group of a File

- Change the Group of a File Using GID

- Change Owner and the Group

- Change Group to a Users Login Group

- Transfer Ownership and Group Settings from One File to Another

- Check Owner and Group Before Making Changes

- Check Owner Only

- Check Group Only

- How to Recursively Change File Ownership

- Chown Command and Symbolic Links

- Display Chown Command Process Details

- Suppress Chown Command Errors

- Linux chown command

- What is file «ownership»?

- Syntax

- Specifying the new owner

- Notes on usage

- Options

- Options

- Options

- Exit status

- Why change a file’s ownership?

- Hypothetical scenarios

- Groups in Linux

- Other operating system groups

- Examples

- Viewing ownership

- Changing ownership

- Related commands

Chown Command: Change Owner of File in Linux

Home » SysAdmin » Chown Command: Change Owner of File in Linux

The chown command changes user ownership of a file, directory, or link in Linux. Every file is associated with an owning user or group. It is critical to configure file and folder permissions properly.

In this tutorial, learn how to use the Linux chown command with examples provided.

- Linux or UNIX-like system

- Access to a terminal/command line

- A user with sudo privileges to change the ownership. Remember to run the commands with sudo to execute them properly.

Linux Chown Command Syntax

The basic chown command syntax consists of a few segments. The help file shows the following format:

- [OPTIONS] – the command can be used with or without additional options.

- [USER] – the username or the numeric user ID of the new owner of a file.

- [:] – use the colon when changing a group of a file.

- [GROUP] – changing the group ownership of a file is optional.

- FILE – the target file.

Superuser permissions are necessary to execute the chown command.

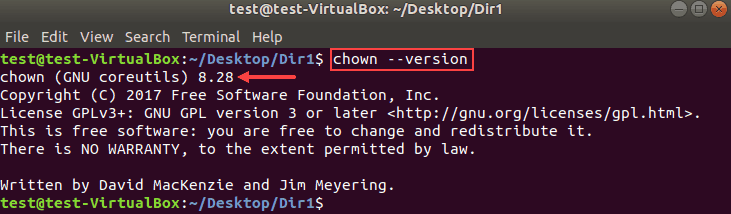

In this guide, we tested the command examples with the chown version 8.28 in Ubuntu 18.04.2 LTS.

To check the chown version on your machine, enter:

The output will look similar to this:

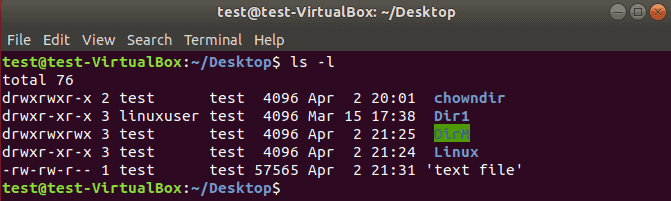

How to Check Ownership of a File in Linux

First, you need to know the original file owner or group before making ownership changes using the chown command.

To check the group or ownership of Linux files and directories in the current location, run the following command:

An example output of the ls command looks like this:

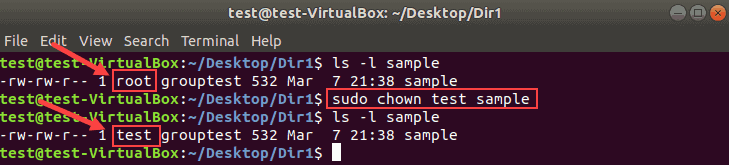

How to Change the Owner of a File

Changing the owner of a file with chown requires you to specify the new owner and the file. The format of the command is:

The following command changes the ownership of a file sample from root to the user test:

Use the same format to change the ownership for both files and directories.

Change the Owner of a File With UID

Instead of a username, you can specify a user ID to change the ownership of a file.

Make sure there is no user with the same name as the numeric UID. If there is, the chown command gives priority to the username, not the UID.

Note: To check a user’s ID, run id -u USERNAME from the terminal.

Change Ownership of Multiple Linux Files

List the target file names after the new user to change the ownership for multiple files. Use single spaces between the file names.

In the following example, root will be the new owner of files sample2 and sample3.

Combine file names and directory names to change their ownership with one command. For example:

Do not forget that the commands are case sensitive.

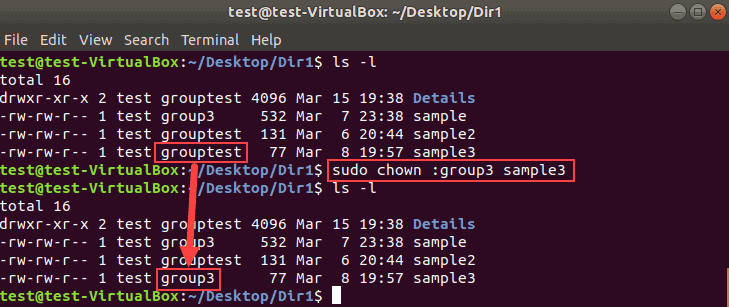

How to Change the Group of a File

With chown, you can change a group for a file or directory without changing the owning user. The result is the same as using the chgrp command.

Run the chown command using the colon and a group name:

The following example changes the group of the file sample3 from grouptest to group3.

List multiple names of files or directories to make bulk changes.

Change the Group of a File Using GID

Similar to UID, use a group ID (GID) instead of a group name to change the group of a file.

Change Owner and the Group

To assign a new owner of a file and change its group at the same time, run the chown command in this format:

Therefore, to set linuxuser as the new owner and group2 as the new group of the file sample2:

Remember that there are no spaces before or after the colon.

Change Group to a Users Login Group

The chown command assigns the owner’s login group to the file when no group is specified.

To do so, define a new user followed by a colon, space, and the target file:

The following example changes the group ownership to the login group of linuxuser:

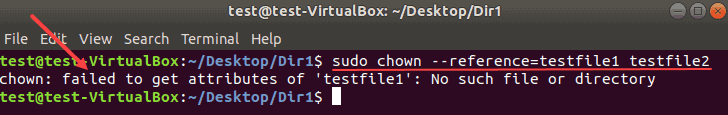

Transfer Ownership and Group Settings from One File to Another

Rather than changing the ownership to a specific user, you can use the owner and a group of a reference file.

Add the —reference option to the chown command to copy the settings from one file to another:

Remember to type in the names of the files correctly to avoid the error message:

Check Owner and Group Before Making Changes

The chown command —from option lets you verify the current owner and group and then apply changes.

The chown syntax for checking both the user and group looks like this:

The example below shows we first verified the ownership and the group of the file sample3:

Then chown changed the owner to linuxuser and the group to group3.

Check Owner Only

The option —from can be used to validate only the current user of a file.

Check Group Only

Similar to the previous section, you can validate only the group of a file using the option —from .

Here is an example where we verified the current group before changing it:

Remember to use the colon for both group names to avoid error messages.

How to Recursively Change File Ownership

The chown command allows changing the ownership of all files and subdirectories within a specified directory. Add the -R option to the command to do so:

In the following example, we will recursively change the owner and the group for all files and directories in Dir1.

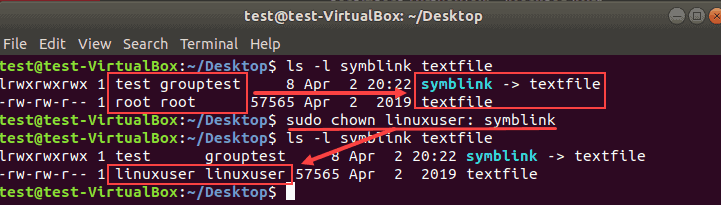

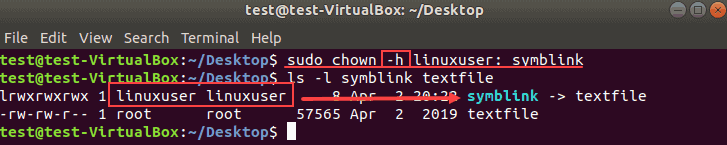

Chown Command and Symbolic Links

To change the owner of a symbolic link, use the -h option. Otherwise, the ownership of the linked file will be changed.

The following image shows how symbolic links behave when -h is omitted.

The owner and group of the symbolic link remain intact. Instead, the owner and the group of the file textfile changed.

To push the changes to the link, run the chown command with the -h flag:

In the following example, we changed the owner and group of a symbolic link.

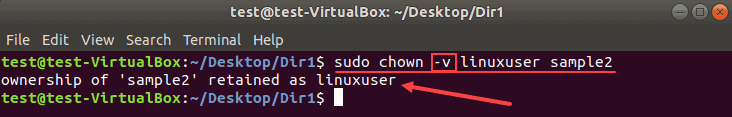

Display Chown Command Process Details

By default, the terminal does not display the chown process information. To see what happens under the hood, use one of the two command line flags:

- The option –v produces the process details even when the ownership stays the same.

- The option –c displays the output information only when an owner or group of the target file changes.

For example, if we specify the current owner as a new owner of the file:

The terminal produces the following output:

Switch from -v to -c and there will be no messages in this case. This happens because there are no owner or group changes.

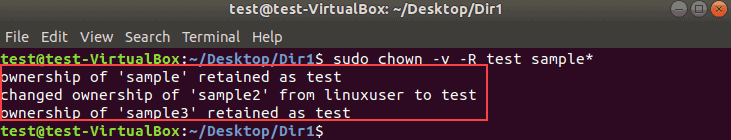

The information is particularly useful with the recursive chown command:

In this example, the output lists all objects affected after running the command.

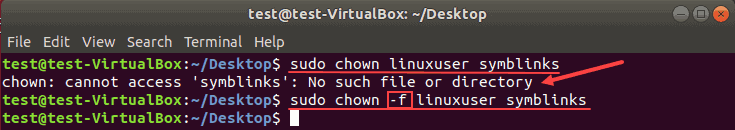

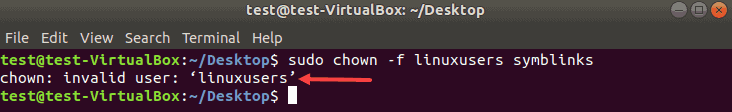

Suppress Chown Command Errors

To avoid seeing potential error messages when running the chown command, use the -f option:

The example below shows the error message for a non-existent file or directory:

Adding the -f flag suppresses most error messages. However, if you specify an invalid username, the error message appears:

Now you know how to use chown command in Linux to change a file’s user and/or group ownership.

Take extra caution when changing the group or ownership of a file or directories.

Источник

Linux chown command

On Unix-like operating systems, the chown command changes ownership of files and directories in a filesystem.

This page describes the GNU/Linux version of chown.

What is file «ownership»?

Linux is designed to support a large number of users. Because of this, it needs to keep careful track of who is allowed to access a file, and how they can access it. These access rules are called permissions.

There are three major types of file permissions:

- User permissions. These permissions apply to a single user who has special access to the file. This user is called the owner.

- Group permissions. These apply to a single group of users who have access to the file. This group is the owning group.

- Other permissions. These apply to every other user on the system. These users are known as others, or the world.

When a file is created, its owner is the user who created it, and the owning group is the user’s current group.

chown can change these values to something else.

Syntax

Specifying the new owner

New ownership of file is specified by the argument new-owner, which takes this general form:

Specifically, there are five ways to format new-owner:

| new-owner form | Description |

|---|---|

| user | The name of the user to own the file. In this form, the colon («:«) and the group is omitted. The owning group is not altered. |

| user:group | The user and group to own the file, separated by a colon, with no spaces between. |

| :group | The group to own the file. In this form, user is omitted, and the group must be preceded by a colon. |

| user: | If group is omitted, but a colon follows user, the owner is changed to user, and the owning group is changed to the login group of user. |

| : | Specifying a colon with no user or group is accepted, but ownership isn’t changed. This form does not cause an error, but changes nothing. |

Notes on usage

- user and group can be specified by name or by number.

- Only root can change the owner of a file. The owner cannot transfer ownership, unless the owner is root, or uses sudo to run the command.

- The owning group of a file can be changed by the file’s owner, if the owner belongs to that group. The owning group of a file can be changed, by root, to any group. Members of the owning group other than the owner cannot change the file’s owning group.

- The owning group can also be changed using the chgrp command. chgrp and chown use the same system call, and are functionally identical.

- Certain miscellaneous file operations can be performed only by the owner or root. For instance, only owner or root can manually change a file’s «atime» or «mtime» (access time or modification time) using the touch command.

- Because of these restrictions, run chown as root, or with sudo.

Options

| Option | Description |

|---|---|

| -c, —changes | Similar to —verbose mode, but only displays information about files that are actually changed. For example: |

—verbose

—silent,

—quiet

—no-dereference

—recursive

Options

The following options modify how a hierarchy is traversed when the -R or —recursive option is specified.

| Option | Description |

|---|---|

| —preserve-root | Never operate recursively on the root directory /. If —recursive is not specified, this option has no effect. |

| -H | If a file specified on the command line is a symbolic link to a directory, traverse it and operate on those files and directories as well. |

| -L | Traverse all symbolic links to a directories. |

| -P | Do not traverse any symbolic links; operate on the symlinks themselves. This is the default behavior. |

If more than one of -H, -L, or -P is specified, only the final option takes effect.

Options

These options display information about the program, and cannot be used with other options or arguments.

| Option | Description |

|---|---|

| —help | Display a brief help message and exit. |

| —version | Display version information and exit. |

Exit status

chown exits with a status of 0 for success. Any other number indicates failed operation.

Why change a file’s ownership?

You should use chown when you want a file’s user or group permissions to apply to a different user or group.

Hypothetical scenarios

Here are examples of when you might use chown:

- You create a file, myfile.txt, using sudo or while logged in as root, so the file is owned by root. However, you intend the file to be used by your regular user account, myuser.

Use chown to change the owner:

- You own myfile.txt, but you want to give it to another user on the system named notme. You also want to change the owning group to that user’s group, notmygroup.

Use chown to change the owner and group:

- You just transferred an entire directory of files, otherfiles, from another computer. All the files and directories are owned by your username on the other system, and you want your current user and group to own them all.

Change the ownership of the directory and all its contents recursively, with the -R option:

The above command changes the ownership of every file, subdirectory, and subdirectory contents in otherfiles.

Groups in Linux

In Linux, a user is a member of multiple groups, but it has only one «current group». The user’s current group is the user’s group identity, or GID.

When the user creates a new file, the file’s ownership is set to the user’s UID (user identity) and GID (group identity). So when user carla starts writing a new document, the file is owned by carla, and also by her current group. She can change the file’s group ownership with chown, but only root can use chown to change the owner to someone else.

Also, each user has a configurable login group, which can be any of the user groups. So when carla logs in, her login group is her current group. The login group can be changed with the usermod command, using the -g option.

A user can change current group with the newgrp command. The change takes place in a subshell, and persists until the subshell is closed. Even if carla changes her current group with newgrp, it will be reset to her login group the next time she logs in.

You can check your current group using the id command with the -g option:

This is your numeric GID (the number of your current group). To see the name, specify the -n option:

To view all of your group memberships, use a capital G:

By default, every Linux user has a private group, with that user as the only member. So, when the user account jeff is created with the adduser command, a group named jeff is also created. Group jeff is jeff’s default login group, and has only one member (jeff).

Other operating system groups

Other operating systems use chown, but their groups may function differently.

In macOS X and BSD, for example, users don’t have private groups. Instead, all regular users belong to a general group called users.

In these operating systems, the options and functionality of chown may be similar, but different. If you’re using chown on a non-Linux operating system, make sure to run man chown to learn what the differences are.

Examples

Viewing ownership

Before you use chown, you may want to check the current ownership of a file. You can view a file’s ownership, permissions, and other important information with the ls command, using the -l option:

In the output, you see several fields of information listed, including the permissions and ownership of the file. It might not make sense at first, so let’s describe it in detail.

Here’s what the information means:

| Data | Field position | Description |

|---|---|---|

| — | Field 1, character 1 | File type: d for a directory, l (lowercase L) for a symbolic link, or — (a dash) for a regular file. |

| rwx | Field 1, characters 2—4 | User permissions. The owner can read («r«), write to («w«), and execute («x«) this file. |

| rw- | Field 1, characters 5—7 | Group permissions. The owning group can read and write to this file, but cannot execute it as a command. |

| r— | Field 1, characters 8—10 | Other permissions, also known as world permissions. Any other user on the system is allowed to read the file only. |

| 1 | Field 2 | Number of symbolic links to this file. If there are no symbolic links to the file, this number is 1, because the original file name is included in this count. If there were one symbolic link to the file, this number would be 2, or 3 for two symbolic links, etc. |

| hope | Field 3 | Name of owner. This is the name of the user who owns the file. When this user tries to access the file, access is restricted according to the user permissions. |

| hopeusers | Field 4 | Name of owning group. This is the user group who owns the file. When a user who is a member of this group tries to access the file, access is restricted according to the group permissions. |

| 12 | Field 5 | Size. This file contains 12 bytes of data. |

| Nov | Field 6 | Mtime (month). Abbreviated name of the month when the file’s contents were last modified. This file was last modified in the month of November. |

| 5 | Field 7 | Mtime (day of month). This file was last modified on the fifth day of November. |

| 13:14 | Field 8 | Mtime (time, or year). This file was last modified at 13:14 (1:34 P.M.) on November 5 of this year. If it was modified over a year ago, this field lists the year instead, for instance 2015. |

| myscript.sh | Field 9 | File name. The name of the file. |

So the important fields here are 1, 3 and 4. They tell us that user hope can read, write, or execute the file’s contents, and members of the group hopeusers can read or write to it.

Changing ownership

Change the owner of file.txt to user hope.

Change the owner of file1, file2, and file3 to user hope.

Here, the asterisk («*«) is a wildcard which the shell expands to a list of every file whose name begins with «file«. If the current directory contains four files named file1, file2, file3, and file4, all these files’ names are passed to the chown command, and their owners changed to user hope.

Change the owner of file or directory myfiles to user hope.

Change the owner of myfiles to user hope. If myfiles is a directory, chown will recursively (-R) search that directory, and change the owner of all files, subdirectories, and subdirectory contents.

Change the owners of file1 and file2 to user hope, and the owning groups to admins.

Change the owner of file1 to user hope, and the owning group to hope’s login group.

Change the owning group of file2 to group othergroup. Notice that this is the only command in these examples which may run without sudo.

If user hope runs the previous command but does not belong to group othergroup, the command fails, unless it is run with sudo.

Change the ownership of file1 to the user with numeric UID 1000, and the group with numeric GID 1001.

Same as the previous command. If user hope has UID 1000, and another user is named «1000» but has UID 1002, this command form (with the «+» signs) unambiguously changes the owner to hope.

Recursively change the ownership of directory Documents, and all files and subdirectories therein, to user hope, group hope.

Recursively change the ownership of the directory

/Documents/work, and all files and subdirectories therein, to match the ownership of the file or directory /home/hope/inbox.

In the above command,

(a tilde) is an alias in bash which represents your home directory. Your home directory can also be represented by the environment variable $HOME, as in $HOME/Documents/work.

Also, if any files change ownership (-c option), information will be printed to standard output:

Related commands

chgrp — Change the group ownership of files or directories.

chmod — Change the permissions of files or directories.

ls — List the contents of a directory or directories.

id — Display group IDs.

usermod — Modify a user’s account settings.

Источник