- Linux edit command

- Description

- Syntax

- Options

- Examples

- Related commands

- How to open, create, edit, and view a file in Linux

- GUI text editors

- NEdit

- Geany

- Gedit

- Terminal-based text editors

- emacs

- Redirecting command output into a text file

- Creating an empty file with the touch command

- Redirecting text into a file

- Redirecting to the end of a file

Linux edit command

On Unix-like operating systems, the edit command is a text editor.

Description

edit is a variant of the text editor ex. It’s recommended for new or casual users who want to use a command-oriented editor. It operates precisely as ex with the following options automatically set:

The following brief introduction should help you get started with edit. If you are using a CRT terminal, you might want to learn about the display editor vi. To edit the contents of an existing file you begin with the command:

edit makes a copy of the file FILENAME which you can then edit. It first tells you how many lines and characters are in the file. If the file does not exist, edit tells you it is a [New File].

The edit command prompt is a colon (:), which is shown after starting the editor. If you are editing an existing file, then you have some lines in edit’s buffer (its name for the copy of the file you are editing). When you start editing, edit makes the last line of the file the current line. Most commands to edit use the current line if you do not tell them which line to use. Thus if you say print (which can be abbreviated p) and enter a carriage return (as you should after all edit commands), the current line is printed. If you delete (d) the current line, edit prints the new current line, which is usually the next line in the file. If you delete the last line, then the new last line becomes the current one.

If you start with an empty file or want to add some new lines, then the append (a) command can be used. After you execute this command (typing a carriage return after the word append), edit reads lines from your terminal until you type a line consisting of a dot (.); it places these lines after the current line. The last line you type then becomes the current line. The insert (i) command is like append, but places the lines you type before, rather than after, the current line.

The edit utility numbers the lines in the buffer, with the first line having number 1. If you execute the command 1, then edit types the first line of the buffer. If you then execute the command d, edit deletes the first line, line 2 becomes line 1, and edit prints the current line (the new line 1) so you can see where you are. In general, the current line is always the last line affected by a command.

You can make a change to some text in the current line using the substitute (s) command:

where old is the string of characters you want to replace and new is the string of characters you want to replace old with.

The file name (f) command tells you how many lines there are in the buffer you are editing and says [Modified] if you have changed the buffer. After modifying a file, you can save the contents of the file by executing a write (w) command. You can leave the editor by issuing a quit (q) command. If you run edit on a file, but do not change it, it is not necessary (but does no harm) to write the file back. If you try to quit from edit after modifying the buffer without writing it out, you receive the message «No write since last change (:quit! overrides)«, and edit waits for another command. If you do not want to write the buffer out, issue the quit command followed by an exclamation point (q!). The buffer is then irretrievably discarded and you return to the shell.

Using the d and a commands and giving line numbers to see lines in the file, you can make any changes you want. Learn at least a few more things, however, if you use edit more than a few times.

The change (c) command changes the current line to a sequence of lines you supply (as in append, you type lines up to a line consisting of only a dot (.). You can tell change to change more than one line by giving the line numbers of the lines you want to change, that is, 3,5c. You can print lines this way too: 1,23p prints the first 23 lines of the file.

The undo (u) command reverses the effect of the last command you executed that changed the buffer. So if you execute a substitute command that does not do what you want, type u and the old contents of the line are restored. You can also undo an undo command. edit gives you a warning message when a command affects more than one line of the buffer. Note that commands such as write and quit cannot be undone.

To look at the next line in the buffer, type a carriage return. To look at several lines, type ^D (while holding down Ctrl , press D ) rather than carriage return. This shows you a half-screen of lines on a CRT or 12 lines on a hardcopy terminal. You can look at nearby text by executing the z command. The current line appears in the middle of the text displayed, and the last line displayed becomes the current line; you can get back to the line where you were before you executed the z command by typing ». The z command has other options: z- prints a screen of text (or 24 lines) ending where you are; z+ prints the next screenful. If you want less than a screenful of lines, type z.11 to display five lines before and five lines after the current line. (Typing z.n, when n is an odd number, displays a total of n lines, centered about the current line; when n is an even number, it displays n-1 lines, so that the lines displayed are centered around the current line.) You can give counts after other commands; for example, you can delete 5 lines starting with the current line with the command d5.

To find things in the file, you can use line numbers if you happen to know them; since the line numbers change when you insert and delete lines this is somewhat unreliable. You can search backwards and forwards in the file for strings by giving commands of the form /text/ to search forward for text or ?text? to search backward for text. If a search reaches the end of the file without finding text, it wraps around and continues to search back to the line where you are. A useful feature here is a search of the form /^text/ which searches for text at the beginning of a line. Similarly /text$/ searches for text at the end of a line. You can leave off the trailing / or ? in these commands.

The current line has the symbolic name dot (.); this is most useful in a range of lines as in .,$p which prints the current line plus the rest of the lines in the file. To move to the last line in the file, you can refer to it by its symbolic name $. Thus the command $d deletes the last line in the file, no matter what the current line is. Arithmetic with line references is also possible: the line $-5 is the fifth before the last and .+20 is 20 lines after the current line.

You can find out the current line by typing ‘.=‘. This is useful if you want to move or copy a section of text within a file or between files. Find the first and last line numbers you want to copy or move. To move lines 10 through 20, type 10,20d a to delete these lines from the file and place them in a buffer named a. edit has 26 such buffers named a through z. To put the contents of buffer a after the current line, type put a. If you want to move or copy these lines to another file, execute an edit (e) command after copying the lines; following the e command with the name of the other file you want to edit, that is, edit chapter2. To copy lines without deleting them, use yank (y) in place of d. If the text you want to move or copy is all within one file, it is not necessary to use named buffers. For example, to move lines 10 through 20 to the end of the file, type 10,20m $.

Syntax

Options

| —, -s | Suppress all interactive user feedback. This is useful when processing editor scripts. |

| -l | Set up for editing LISP programs. |

| -L | List the name of all files saved as the result of an editor or system crash. |

| -R | Read only mode; the read-only flag is set, preventing accidental overwriting of the file. |

| -r filename | Edit file name after an editor or system crash. (Recovers the version of file name that was in the buffer when the crash occurred.) |

| -t tag | Edit the file containing the tag tag and position the editor at its definition. |

| -v | Start up in display editing state using vi. You can achieve the same effect by typing the vi command itself. |

| -V | Verbose mode. When ex commands are read by means of standard input, the input will be echoed to standard error. This may be useful when processing ex commands within shell scripts. |

| -x | Encryption option; when used, edit simulates the X command of ex and prompts the user for a key. This key is used to encrypt and decrypt text using the algorithm of the crypt command. The X command makes an educated guess to determine whether text read in is encrypted or not. The temporary buffer file is encrypted also, using a transformed version of the key typed in for the -x option. |

| -wn | Set the default window size to n. This is useful when using the editor over a slow speed line. |

| -C | Encryption option; same as the -x option, except that vi simulates the C command of ex. The C command is like the X command of ex, except that all text read in is assumed to have been encrypted. |

| +command, —command | Begin editing by executing the specified editor command (usually a search or positioning command). |

| filename | The name of the file that you want to edit. |

Examples

Loads myfile.txt for editing, and places the user at the editing command prompt.

Related commands

ed — A simple text editor.

ex — Line-editor mode of the vi text editor.

vi — Text editor based on the visual mode of ex.

Источник

How to open, create, edit, and view a file in Linux

One thing GNU/Linux does as well as any other operating system is give you the tools you need to create and edit text files. Ask ten Linux users to name their favorite text editor, and you might get ten different answers. On this page, we cover a few of the many text editors available for Linux.

GUI text editors

This section discusses text editing applications for the Linux windowing system, X Windows, more commonly known as X11 or X.

If you are coming from Microsoft Windows, you are no doubt familiar with the classic Windows text editor, Notepad. Linux offers many similar programs, including NEdit, gedit, and geany. Each of these programs are free software, and they each provide roughly the same functionality. It’s up to you to decide which one feels best and has the best interface for you. All three of these programs support syntax highlighting, which helps with editing source code or documents written in a markup language such as HTML or CSS.

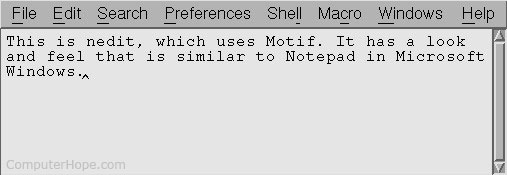

NEdit

NEdit, which is short for the Nirvana Editor, is a straightforward text editor that is very similar to Notepad. It uses a Motif-style interface.

The NEdit homepage is located at https://sourceforge.net/projects/nedit/. If you are on a Debian or Ubuntu system, you can install NEdit with the following command:

For more information, see our NEdit information page.

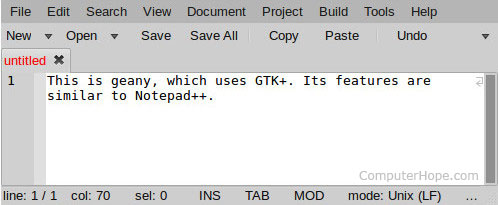

Geany

Geany is a text editor that is a lot like Notepad++ for Windows. It provides a tabbed interface for working with multiple open files at once and has nifty features like displaying line numbers in the margin. It uses the GTK+ interface toolkit.

The Geany homepage is located at http://www.geany.org/. On Debian and Ubuntu systems, you can install Geany by running the command:

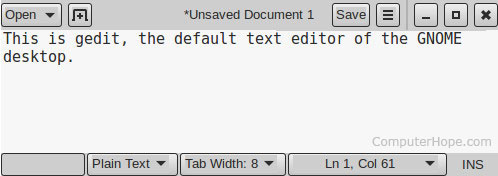

Gedit

Gedit is the default text editor of the GNOME desktop environment. It’s a great, text editor that can be used on about any Linux system.

The Gedit homepage is located at https://wiki.gnome.org/Apps/Gedit. On Debian and Ubuntu systems, Gedit can be installed by running the following command:

Terminal-based text editors

If you are working from the Linux command line interface and you need a text editor, you have many options. Here are some of the most popular:

pico started out as the editor built into the text-based e-mail program pine, and it was eventually packaged as a stand-alone program for editing text files. («pico» is a scientific prefix for very small things.)

The modern version of pine is called alpine, but pico is still called pico. You can find more information about how to use it in our pico command documentation.

On Debian and Ubuntu Linux systems, you can install pico using the command:

nano is the GNU version of pico and is essentially the same program under a different name.

On Debian and Ubuntu Linux systems, nano can be installed with the command:

vim, which stands for «vi improved,» is a text editor used by millions of computing professionals all over the world. Its controls are a little confusing at first, but once you get the hang of them, vim makes executing complex editing tasks fast and easy. For more information, see our in-depth vim guide.

On Debian and Ubuntu Linux systems, vim can be installed using the command:

emacs

emacs is a complex, highly customizable text editor with a built-in interpreter for the Lisp programming language. It is used religiously by some computer programmers, especially those who write computer programs in Lisp dialects such as Scheme. For more information, see our emacs information page.

On Debian and Ubuntu Linux systems, emacs can be installed using the command:

Redirecting command output into a text file

When at the Linux command line, you sometimes want to create or make changes to a text file without actually running a text editor. Here are some commands you might find useful.

Creating an empty file with the touch command

To create an empty file, it’s common to use the command touch. The touch command updates the atime and mtime attributes of a file as if the contents of the file had been changed — without actually changing anything. If you touch a file that doesn’t exist, the system creates the file without putting any data inside.

For instance, the command:

The above command creates a new, empty file called myfile.txt if that file does not already exist.

Redirecting text into a file

Sometimes you need to stick the output of a command into a file. To accomplish this quickly and easily, you can use the > symbol to redirect the output to a file.

For instance, the echo command is used to «echo» text as output. By default, this goes to the standard output — the screen. So the command:

The above command prints that text on your screen and return you to the command prompt. However, you can use > to redirect this output to a file. For instance:

The above command puts the text «Example text» into the file myfile.txt. If myfile.txt does not exist, it is created. If it already exists, its contents will be overwritten, destroying the previous contents and replacing them.

Be careful when redirecting output to a file using >. It will overwrite the previous contents of the file if it already exists. There is no undo for this operation, so make sure you want to completely replace the file’s contents before you run the command.

Here’s an example using another command:

The above command executes ls with the -l option, which gives a detailed list of files in the current directory. The > operator redirects the output to the file directory.txt, instead of printing it to the screen. If directory.txt does not exist, it is created first. If it already exists, its contents will be replaced.

Redirecting to the end of a file

The redirect operator >> is similar to >, but instead of overwriting the file contents, it appends the new data to the end of the file. For instance, the command:

Источник