- How To Increase Amount of Disk inodes in Linux

- How to Increase Disk Inode Number in Linux

- If You Appreciate What We Do Here On TecMint, You Should Consider:

- ☩ Walking in Light with Christ – Faith, Computing, Diary

- What is inode and how to find out which directory is eating up all your filesystem inodes on Linux, Increase inode count on a ext3 ext4 and ufs filesystems

- What are filesystem i-nodes?

- What is typical content of inode and how I-nodes play with rest of Filesystem units?

- Listing inodes on a Fileystem

- Getting more extensive information on a mounted filesystem

- How to Get inodes per mounted filesystem

- Finding files with a certain inode

- Find directory that has a large number of files in it?

- Print top 10 subdirectories with Highest Inode Usage

- How to Increase the amount of Inodes count on a new created volume EXT4 filesystem

- Increase the Max Count of Inodes for a /tmp filesystem

How To Increase Amount of Disk inodes in Linux

Mattias Geniar, August 02, 2015

Follow me on Twitter as @mattiasgeniar

It doesn’t happen often, but at times you may run out of inodes on a Linux system.

To find your current inode usage, run df -i .

Out of the available 19.374.080 inodes, none were free. This is pretty much the equivalent of a disk full, except it doesn’t show in terms of capacity but in terms of inodes.

If you’re confused on what an inode exactly is, Wikipedia has a good description.

In a Unix-style file system, an index node, informally referred to as an inode, is a data structure used to represent a filesystem object, which can be one of various things including a file or a directory. Each inode stores the attributes and disk block location(s) of the filesystem object’s data.

A disk with 0 available inodes is probably full of very small files, somewhere in a specific directory (applications, tmp-files, pid files, session files, …). Each file uses (at least) 1 inode. Many million files would use many million inodes.

If your disks’ inodes are full, how do you increase it? The tricky answer is, you probably can’t.

The amount of inodes available on a system is decided upon creation of the partition. For instance, a default partition of EXT3/EXT4 has a bytes-per-inode ratio of one inode every 16384 bytes (16 Kb).

A 10GB partition would have would have around 622.592 inodes. A 100GB partition has around 5.976.883,2 inodes (taking into account the reserved space for super-users/journalling).

Do you want to increase the amount of inodes? Either increase the capacity of the disk entirely (Guide: Increase A VMware Disk Size (VMDK) LVM), or re-format the disk using mkfs.ext4 -i to manually overwrite the bytes-per-inode ratio.

As usual, the Archwiki has a good explanation on why we don’t just make the default inode number 10x higher.

For partitions with size in the hundreds or thousands of GB and average file size in the megabyte range, this usually results in a much too large inode number because the number of files created never reaches the number of inodes.

This results in a waste of disk space, because all those unused inodes each take up 256 bytes on the filesystem (this is also set in /etc/mke2fs.conf but should not be changed). 256 * several millions = quite a few gigabytes wasted in unused inodes.

You may be able to create a new partition if you have spare disks/space in your LVM and chose a filesystem that’s better suited to handle many small files, like ReiserFS.

Источник

How to Increase Disk Inode Number in Linux

When a new file system is created on a partition on a disk in Linux, and the kernel keeps aside space for inodes during the initial structuring of the file system. The number of inodes within a file system directly affects the number of files (i.e the maximum number of inodes, and hence the maximum number of files, is set when the file system is created).

If all inodes in a file system are exhausted, the kernel can not create new files even when there is available space on the disk. In this short article, we will show you how to increase the number of inodes in a file system in Linux.

When creating a new file system on a partition, you can use the -i option to set the bytes-per-inode (bytes/inode ratio), the larger the bytes-per-inode ratio, the fewer inodes will be created.

The following example shows how to create an EXT4 file system type with a small bytes-per-inode ratio on a 4GB partition.

Note: Once the file system is created, you can not change the bytes-per-inode ratio (unless you re-format it), and resizing a filesystem changes the number of inodes to maintain this ratio.

Here is another example with a larger bytes-per-inode ratio.

Besides, you can also use the -T flag to specify how the filesystem is going to be used so that mkfs.ext4 can choose optimal filesystem parameters for that use including the bytes-per-inode ratio. The configuration file /etc/mke2fs.conf contains the different supported usage types and many other configurations parameters.

In the following examples, the command tells that the file system will be used to create and/or store largefile and largefile4 which offer more relevant ratios of one inode every 1 MiB and 4 MiB respectively.

To check the inode usage of a file system, run the df command with the -i option (the -T option shows the file system type).

We would like to know your thoughts about this article. Use the feedback form below to reach us. For more information, see the mkfs.ext4 manpage.

If You Appreciate What We Do Here On TecMint, You Should Consider:

TecMint is the fastest growing and most trusted community site for any kind of Linux Articles, Guides and Books on the web. Millions of people visit TecMint! to search or browse the thousands of published articles available FREELY to all.

If you like what you are reading, please consider buying us a coffee ( or 2 ) as a token of appreciation.

We are thankful for your never ending support.

Источник

☩ Walking in Light with Christ – Faith, Computing, Diary

What is inode and how to find out which directory is eating up all your filesystem inodes on Linux, Increase inode count on a ext3 ext4 and ufs filesystems

Tuesday, 20th August 2019

If you’re a system administrator of multiple Linux servers used for Web serving delivery / Mail server sysadmin, Database admin or any High amount of Drives Data Storage used for backup servers infra, Data Repository administrator such as Linux hosted Samba / CIFS shares, etc. or using some Linux Hosting Provider to host your website or any other UNIX like Infrastructure servers that demands a storage of high number of files under a Directory you might end up with the common filesystem inode depletion issues ( Maximum Inode number for a filesystem is predefined, limited and depending on the filesystem configured size).

In case a directory stored files end up exceding the amount of possible addressable inodes could prevent any data to be further assiged and stored on the Filesystem.

Reaching maximum inodes number (e.g. inode depletion), often happens on Busy Mail servers (receivng tons of SPAM email messages) or Content Delivery Network (CDN – Website Image caching servers) which contain many small files on EXT3 or EXT4 Journalled filesystems. File systems (such as Btrfs, JFS or XFS) escape this limitation with extents or dynamic inode allocation, which can ‘grow’ the file system or increase the number of inodes.

Hence ending being out of inodes could cause various oddities on how stored data behaves or communicated to other connected microservices and could lead to random application disruptions and odd results costing you many hours of various debugging to find the root cause of inodes (index nodes) being out of order.

In below article, I will try to give an overall explanation on what is an I-Node on a filesystem, how inodes of FS unit could be seen, how to diagnose a possible inode poblem – e.g. see the maximum amount of inodes available per filesystem and how to prepare (format) a new filesystem with incrsed set of maximum inodes.

What are filesystem i-nodes?

This is a data structure in a Unix-style file system that describes a file-system object such as a file or a directory.

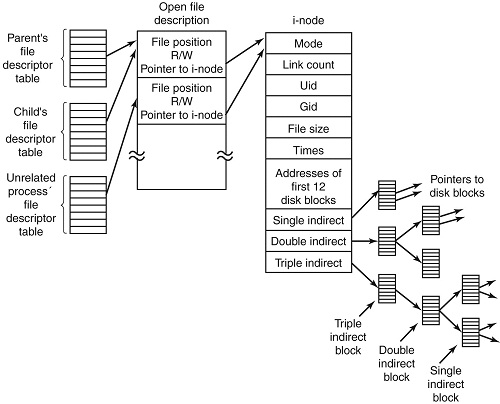

The data structure described in the inodes might vary slightly depending on the filesystem but usually on EXT3 / EXT4 Linux filesystems each inode stores the index to block that contains attributes and disk block location(s) of the object’s data.

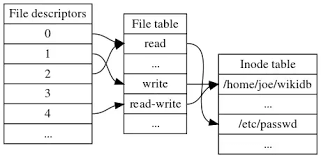

– Yes for those who are not aware on how a filesystem is structured on *nix it does allocate all stored data in logical separeted structures called data blocks. Each file stored on a local filesystem has a file descriptor, there are virtual unit structures file tables and each of the inodes that are a reference number has a own data structure (inode table).

Inodes / «Index» are slightly unusual on file system structure that stored the access information of files as a flat array on the disk, with all the hierarchical directory information living aside from this as explained by Unix creator and pioneer- Dennis Ritchie (passed away few years ago).

Simplified explanation on file descriptors, file table and inode, table on a common Linux filesystem

Here is another description on what is I-node, given by Ken Thompson (another Unix pioneer and father of Unix) and Denis Ritchie, described in their paper published in 1978:

» As mentioned in Section 3.2 above, a directory entry contains only a name for the associated file and a pointer to the file itself. This pointer is an integer called the i-number (for index number) of the file. When the file is accessed, its i-number is used as an index into a system table (the i-list) stored in a known part of the device on which the directory resides. The entry found thereby (the file’s i-node) contains the description of the file:…

— The UNIX Time-Sharing System, The Bell System Technical Journal, 1978 «

What is typical content of inode and how I-nodes play with rest of Filesystem units?

The inode is just a reference index to a data block (unit) that contains File-system object attributes. It may include metadata information such as (times of last change, access, modification), as well as owner and permission data.

On a Linux / Unix filesystem, directories are lists of names assigned to inodes. A directory contains an entry for itself, its parent, and each of its children.

Structure of inode table-on Linux Filesystem diagram (picture source GeeksForGeeks.org)

- Information about files(data) are sometimes called metadata. So you can even say it in another way, «An inode is metadata of the data.»

- Inode : Its a complex data-structure that contains all the necessary information to specify a file. It includes the memory layout of the file on disk, file permissions, access time, number of different links to the file etc.

- Global File table : It contains information that is global to the kernel e.g. the byte offset in the file where the user’s next read/write will start and the access rights allowed to the opening process.

- Process file descriptor table : maintained by the kernel, that in turn indexes into a system-wide table of files opened by all processes, called the file table .

The inode number indexes a table of inodes in a known location on the device. From the inode number, the kernel’s file system driver can access the inode contents, including the location of the file – thus allowing access to the file.

- Inodes do not contain its hardlink names, only other file metadata.

- Unix directories are lists of association structures, each of which contains one filename and one inode number.

- The file system driver must search a directory looking for a particular filename and then convert the filename to the correct corresponding inode number.

The operating system kernel’s in-memory representation of this data is called struct inode in Linux. Systems derived from BSD use the term vnode, with the v of vnode referring to the kernel’s virtual file system layer.

But enough technical specifics, lets get into some practical experience on managing Filesystem inodes.

Listing inodes on a Fileystem

Lets say we wan to to list an inode number reference ID for the Linux kernel (files):

root@linux: # ls -i /boot/vmlinuz-*

3055760 /boot/vmlinuz-3.2.0-4-amd64 26091901 /boot/vmlinuz-4.9.0-7-amd64

3055719 /boot/vmlinuz-4.19.0-5-amd64 26095807 /boot/vmlinuz-4.9.0-8-amd64

To list an inode of all files in the kernel specific boot directory /boot:

root@linux: # ls -id /boot/

26091521 /boot/

Listing inodes for all files stored in a directory is also done by adding the -i ls command flag:

Note the the ‘-1‘ flag was added to to show files in 1 column without info for ownership permissions

root@linux:/# ls -1i /boot/

26091782 config-3.2.0-4-amd64

3055716 config-4.19.0-5-amd64

26091900 config-4.9.0-7-amd64

26095806 config-4.9.0-8-amd64

26091525 grub/

3055848 initrd.img-3.2.0-4-amd64

3055644 initrd.img-4.19.0-5-amd64

26091902 initrd.img-4.9.0-7-amd64

3055657 initrd.img-4.9.0-8-amd64

26091756 System.map-3.2.0-4-amd64

3055703 System.map-4.19.0-5-amd64

26091899 System.map-4.9.0-7-amd64

26095805 System.map-4.9.0-8-amd64

3055760 vmlinuz-3.2.0-4-amd64

3055719 vmlinuz-4.19.0-5-amd64

26091901 vmlinuz-4.9.0-7-amd64

26095807 vmlinuz-4.9.0-8-amd64

To get more information about Linux directory, file, such as blocks used by file-unit, Last Access, Modify and Change times, current External Symbolic or Static links for filesystem object:

root@linux:/ # stat /etc/

File: /etc/

Size: 16384 Blocks: 32 IO Block: 4096 catalog

Device: 801h/2049d Inode: 6365185 Links: 231

Access: (0755/drwxr-xr-x) Uid: ( 0/ root) Gid: ( 0/ root)

Access: 2019-08-20 06:29:39.946498435 +0300

Modify: 2019-08-14 13:53:51.382564330 +0300

Change: 2019-08-14 13:53:51.382564330 +0300

Birth: –

Within a POSIX system (Linux-es) and *BSD are more or less such, a file has the following attributes[9] which may be retrieved by the stat system call:

– Device ID (this identifies the device containing the file; that is, the scope of uniqueness of the serial number).

File serial numbers.

– The file mode which determines the file type and how the file’s owner, its group, and others can access the file.

– A link count telling how many hard links point to the inode.

– The User ID of the file’s owner.

– The Group ID of the file.

– The device ID of the file if it is a device file.

– The size of the file in bytes.

– Timestamps telling when the inode itself was last modified (ctime, inode change time), the file content last modified (mtime, modification time), and last accessed (atime, access time).

– The preferred I/O block size.

– The number of blocks allocated to this file.

Getting more extensive information on a mounted filesystem

Most Linuxes have the tune2fs installed by default (in debian Linux this is through e2fsprogs) package, with it one can get a very good indepth information on a mounted filesystem, lets say about the ( / ) root FS.

# tune2fs -l /dev/sda1

tune2fs 1.44.5 (15-Dec-2018)

Filesystem volume name:

Last mounted on: /

Filesystem UUID: abe6f5b9-42cb-48b6-ae0a-5dda350bc322

Filesystem magic number: 0xEF53

Filesystem revision #: 1 (dynamic)

Filesystem features: has_journal ext_attr resize_inode dir_index filetype needs_recovery sparse_super large_file

Filesystem flags: signed_directory_hash

Default mount options: (none)

Filesystem state: clean

Errors behavior: Continue

Filesystem OS type: Linux

Inode count: 30162944

Block count: 120648960

Reserved block count: 6032448

Free blocks: 13830683

Free inodes: 26575654

First block: 0

Block size: 4096

Fragment size: 4096

Reserved GDT blocks: 995

Blocks per group: 32768

Fragments per group: 32768

Inodes per group: 8192

Inode blocks per group: 512

Filesystem created: Thu Sep 6 21:44:22 2012

Last mount time: Sat Jul 20 11:33:38 2019

Last write time: Sat Jul 20 11:33:28 2019

Mount count: 6

Maximum mount count: 22

Last checked: Fri May 10 18:32:27 2019

Check interval: 15552000 (6 months)

Next check after: Wed Nov 6 17:32:27 2019

Lifetime writes: 338 GB

Reserved blocks uid: 0 (user root)

Reserved blocks gid: 0 (group root)

First inode: 11

Inode size: 256

Required extra isize: 28

Desired extra isize: 28

Journal inode: 8

First orphan inode: 21554129

Default directory hash: half_md4

Directory Hash Seed: d54c5a90-bc2d-4e22-8889-568d3fd8d54f

Journal backup: inode blocks

Important note to make here is file’s inode number stays the same when it is moved to another directory on the same device, or when the disk is defragmented which may change its physical location. This also implies that completely conforming inode behavior is impossible to implement with many non-Unix file systems, such as FAT and its descendants, which don’t have a way of storing this invariance when both a file’s directory entry and its data are moved around. Also one inode could point to a file and a copy of the file or even a file and a symlink could point to the same inode, below is example:

$ ls -l -i /usr/bin/perl*

266327 -rwxr-xr-x 2 root root 10376 Mar 18 2013 /usr/bin/perl

266327 -rwxr-xr-x 2 root root 10376 Mar 18 2013 /usr/bin/perl5.14.2

A good to know is inodes are always unique values, so you can’t have the same inode number duplicated. If a directory is damaged, only the names of the things are lost and the inodes become the so called “orphan”, e.g. inodes without names but luckily this is recoverable. As the theory behind inodes is quite complicated and is complicated to explain here, I warmly recommend you read Ian Dallen’s Unix / Linux / Filesystems – directories inodes hardlinks tutorial – which is among the best academic Tutorials explaining various specifics about inodes online.

How to Get inodes per mounted filesystem

root@linux:/home/hipo# df -i

Filesystem Inodes IUsed IFree IUse% Mounted on

dev 2041439 481 2040958 1% /dev

tmpfs 2046359 976 2045383 1% /run

tmpfs 2046359 4 2046355 1% /dev/shm

tmpfs 2046359 6 2046353 1% /run/lock

tmpfs 2046359 17 2046342 1% /sys/fs/cgroup

/dev/sdb5 1221600 2562 1219038 1% /usr/var/lib/mysql

/dev/sdb6 6111232 747460 5363772 13% /var/www/htdocs

/dev/sdc1 122093568 3083005 119010563 3% /mnt/backups

tmpfs 2046359 13 2046346 1% /run/user/1000

As you see in above output Inodes reported for each of mounted filesystems has a specific number. In above output IFree on every mounted FS locally on Physical installed OS Linux is good.

Here is an example on how to recognize a depleted Inodes on a OpenXen Virtual Machine with attached Virtual Hard disks.

# df -i

Filesystem Inodes IUsed IFree IUse% Mounted on

/dev/xvda 2080768 2080768 0 100% /

tmpfs 92187 3 92184 1% /lib/init/rw

varrun 92187 38 92149 1% /var/run

varlock 92187 4 92183 1% /var/lock

udev 92187 4404 87783 5% /dev

tmpfs 92187 1 92186 1% /dev/shm

Finding files with a certain inode

At some cases if you want to check all the copy files of a certain file that have the same i-node pointer it is useful to find them all by their shared inode this is possible with simple find (below example is for /usr/bin/perl binary sharing same inode as perl5.28.1:

ls -i /usr/bin/perl

23798851 /usr/bin/perl*

find /usr/bin -inum 435308 -print

/usr/bin/perl5.28.1

/usr/bin/perl

Find directory that has a large number of files in it?

To get an overall number of inodes allocated by a certain directory, lets say /usr /var

root@linux:/var# du -s –inodes /usr /var

566931 /usr

56020 /var/

To get a list of directories use by inode for a directory with its main contained sub-directories sorted from 1 till highest number use:

du -s –inodes * 2>/dev/null |sort -g

Usually running out of inodes means there is a directory / fs mounts that has too many (small files) that are depleting the max count of possible inodes.

The most simple way to list directories and number of files in them on the server root directory is with a small bash shell loop like so:

for i in /*; do echo $i; find $i |wc -l; done

Another way to identify the exact directory that is most likely the bottleneck for the inode depletion in a sorted by file count, human readable form:

find / -xdev -printf ‘%hn’ | sort | uniq -c | sort -k 1 -n

This will dump a list of every directory on the root (/) filesystem prefixed with the number of files (and subdirectories) in that directory. Thus the directory with the largest number of files will be at the bottom.

The -xdev switch is used to instruct find to narrow it’s search to only the device where you’re initiating the search (any other sub-mounted NAS / NFS filesystems from a different device will be omited).

Print top 10 subdirectories with Highest Inode Usage

Once identifed the largest number of files directories that is perhaps the issue, to further get a list of Top subdirectories in it with highest amount of inodes used, use below cmd:

for i in `ls -1A`; do echo «`find $i | sort -u | wc -l` $i»; done | sort -rn | head -10

To list more than 10 of the top inodes used dirs change the head -10 to whatever num needed.

N.B. ! Be very cautious when running above 2 find commands on a very large filesystems as it will be I/O Excessive and in filesystems that has some failing blocks this could create further problems.

To omit putting a high I/O load on a production filesystem, it is possible to also use du + very complex regular expression:

Results returned are from top to bottom.

How to Increase the amount of Inodes count on a new created volume EXT4 filesystem

Some FS-es XFS, JFS do have an auto-increase inode feature in case if their is physical space, whether otheres such as reiserfs does not have inodes at all but still have a field reported when queried for errors. But the classical Linux ext3 / ext4 does not have a way to increase the inode number on a live filesystem. Instead the way to do it there is to prepare a brand new filesystem on a Disk / NAS / attached storage.

The number of inodes at format-time of the block storage can be as high as 4 billion inodes. Before you create the new FS, you have to partition the new the block storage as ext4 with lets say parted command (or nullify the content of an with dd to clean up any previous existing data on a volume if there was already existing data:

then format it with this additional parameter:

mkfs.ext4 -N 3000000000 /dev/path/to/volume

Here in above example the newly created filesystem of EXT4 type will be created with 3 Billion inodes !, for setting a higher number on older ext3 filesystem max inode count mkfs.ext3 could be used instead.

Bear in mind that 3 Billion number is a too high number and if you plan to have some large number of files / directories / links structures just raise it up to your pre-planning requirements for FS. In most cases it will be rarely anyone that want to have this number higher than 1 or 2 billion of inodes.

On FreeBSD / NetBSD / OpenBSD setting inode maximum number for a UFS / UFS2 (which is current default FreeBSD FS), this could be done via newfs filesystem creation command after the disk has been labeled with disklabel:

freebsd# newfs -i 1024 /dev/ada0s1d

Increase the Max Count of Inodes for a /tmp filesystem

Sometimes on some machines it is necessery to have ability to store very high number of small files (e.g. have a very large number of inodes) on a temporary filesystem kept in memory. For example some web applications served by Web Server Apache + PHP, Nginx + Perl-FastCGI are written in a bad manner so they kept tons of temporary files in /tmp, leading to issues with exceeded amount of inodes.

If that’s the case to temporary work around you can increase the count of Inodes for /tmp to a very high number like 2 billions using:

mount -o remount,nr_inodes= /tmp

To make the change permanent on next boot if needed don’t forget to put the nr_inodes=whatever_bignum as a mount option for the temporary fs to /etc/fstab

Eventually, if you face this issues it is best to immediately track which application produced the mess and ask the developer to fix his messed up programs architecture.

Источник