Linux observability with bpf pdf

Linux Observability with BPF code examples

This is the companion code repo for the book Linux Observability with BPF.

We believe that even if the examples included in the book were all tested and working when we wrote them, human error is possible and technology changes. For that reason, the purpose of this repo is to keep them as updated as possible and correct mistakes we made while writing the book.

Nota Bene: All the examples in this repository are adapted from the book to assume that you use the Vagrant environment we provide. Examples can be slightly different in this repository because of that. The reason is that we didn’t want to couple the book itself to Vagrant as a tool. If you don’t want a Vagrant based environment, make sure you have: bcc and clang

- Please expand the details of the environment you want to work on.

- Remember that the examples have been tested on the Vagrant based environment primarily.

- Feel free to open an issue or a PR if you want to help in making this better for everyone!

Fedora 30

First, we need to install some build dependencies and all the tools needed for the examples:

Then we need grab a copy of the source code of the current kernel.

In our case the kernel runing can be verified with uname .

Given that version, please notice the URL we fetch the sources from in the following command. Change it according to your version.

Now that we have the kernel source, we can move it to the /kernel-src folder.

NOTE THAT: All the examples using kernel sources in this repo assume that the kernel sources are available there. In case you don’t like it, make sure you do a search and replace!

At this point we move the kernel sources and compile libbpf . Again please notice the 5.0.9 here and change accordingly.

First, we need to install some build dependencies and all the tools needed for the examples:

Note on Kernel version: make sure to have a recent kernel to run the examples, a version >=5.0.0 will do the job. Most Ubuntu 18.04 providers are shipping with the kernel 4.15 that doesn’t work for most of the examples. Upgrading options are left to the reader, we’ve been successful on aws by installing the linux-image-5.0.0-1019-aws package.

After dependencies, we need grab a copy of the kernel source code for the current release. Since this assumes that you are running an updated Ubuntu 18.04 we can get it directly from the repo they provide.

Now that we have the kernel source, we can move it to the /kernel-src folder.

NOTE THAT: All the examples using kernel sources in this repo assume that the kernel sources are available at /kernel-src . In case you don’t like it, make sure you do a search and replace!

At this point we move the kernel sources and compile libbpf .

Ubuntu doesn’t have the library path that the makefile expects so we need to move our libraries to its library path now.

The environment is based on Fedora 30.

To install Vagrant, follow the official guide here.

Once you have Vagrant installed, you will need to clone this repository and issue a vagrant up .

This Vagrant command, will start a Fedora 30 VM in Virtualbox, you can SSH into the machine using:

Before going on, make sure you download the kernel source tree in this repository. It is needed as a dependency for some examples. We will be downloading the code for Kernel 5.0.9 — We are avoiding a git clone here because the Git history of the kernel is very big.

At this point, we need to compile the libbpf library:

Before going to the examples, it will be useful to have a copy of this repo in your environment.

IMPORTANT NOTE: The examples assume that you clone the repo in your home folder

/linux-observability-with-bpf , if you didn’t do please remember to change your commands!

Yay, at this point you have everything and can follow the following code examples.

Click on each example to follow the setup instructions.

Источник

Brendan Gregg’s Blog

BPF Performance Tools: Linux System and Application Observability (book)

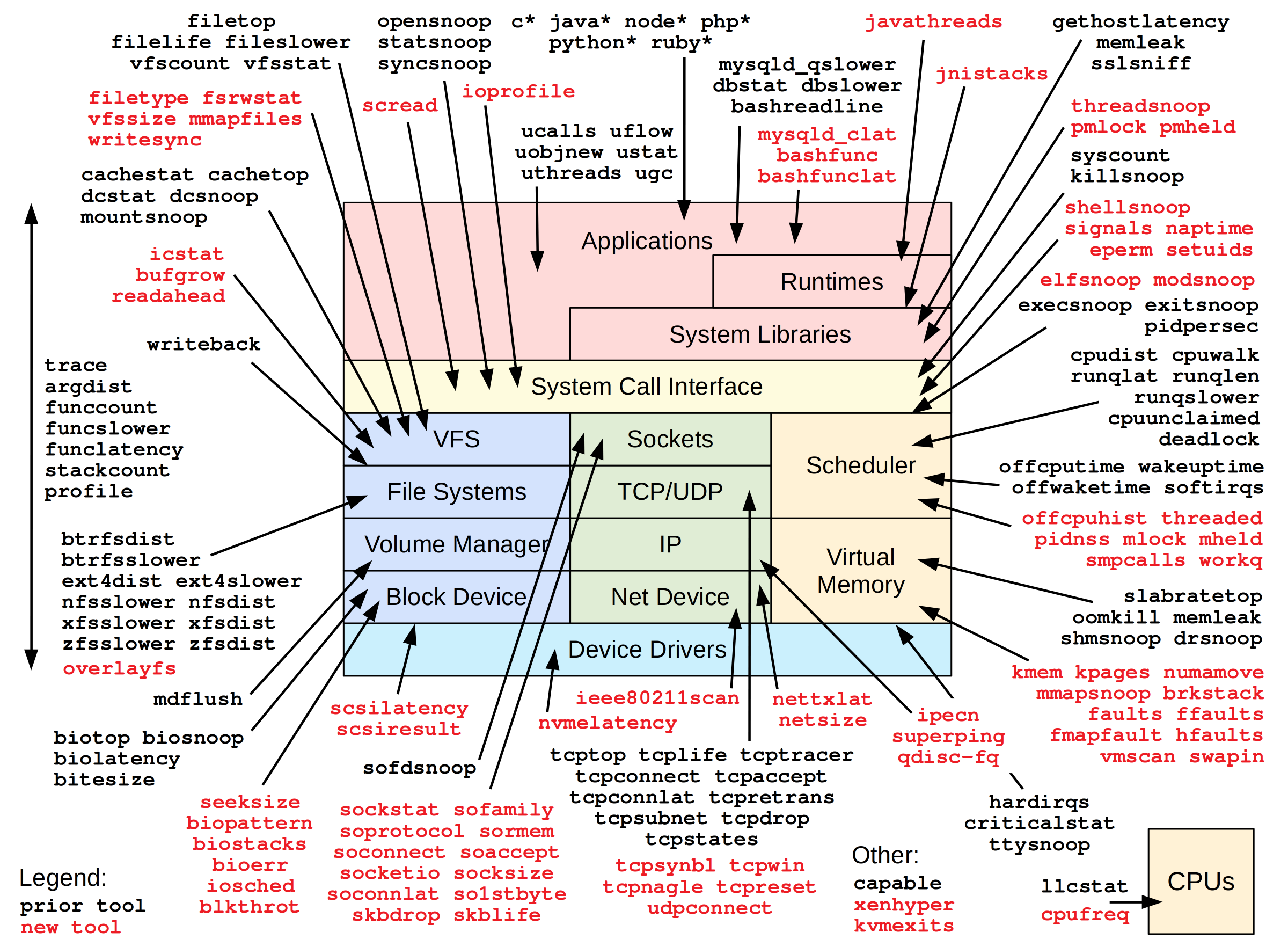

BPF (eBPF) tracing is a superpower that can analyze everything, and I’ll show you how in my upcoming book BPF Performance Tools: Linux System and Application Observability, coming soon from Addison Wesley. The book includes over 150 BPF observability tools that you can run to find performance wins and troubleshoot software, and also shows you how to write your own. Over one hundred of these BPF tools are newly-developed for this book; you can see many of them in this diagram:

I’ve found this diagram to be a useful reminder and checklist when debugging production issues at Netflix, and I have it printed on a wall so I can glance at it. You may find it helps you, too, which is why it is on the cover.

Since BPF does so many things, it is becoming a technology name and no longer an acronym. It originated as Berkeley Packet Filter (BPF), an in-kernel execution engine that processes a virtual instruction set, and has been extended (aka eBPF) for providing a safe way to extend kernel functionality. BPF is in the Linux kernel.

Why Your Book?

BPF is a new in-demand technology, and I expect that, over time, a dozen or more books about it may be published – as happens for other hot new technologies. Guess how many books there are about Docker? I lost count at 30! Some other future BPF books may be good, and I’ll recommend them as appropriate. To answer the question why you should buy my book:

- It is about using BPF for performance analysis, and is written by a veteran performance engineer and technical trainer (myself).

- At over 700 pages, it covers CPUs, memory, disks, file systems, networking, multiple languages, applications, containers, hypervisors, security analysis, and the Linux kernel.

- It contains over 150 tools (often with source code), including over 100 brand-new tools mostly developed by myself, so that you can get started right away finding performance wins in any of those areas.

- It also covers over 30 traditional tools (iostat(1), perf(1), etc) so you can use the right tool for the job, even when that tool is not BPF.

- It goes far beyond what you can find online, which I previously summarized (learn eBPF tracing).

- It focuses on the recommended BPF tracing front ends: BCC and bpftrace.

- It shows production screenshots and use cases from a major site (Netflix), including gotchas we’ve hit in production, such as fixing stacks and symbols, and managing overhead.

- It was developed with the help of many members and leaders of the BPF community.

- I’ve been helping lead BPF observability since 2014, and I’m a major contributor and maintainer for the front-ends. Among other things I created the tutorials and reference guides.

- This is also my fourth book to cover tracing.

I was previously a professional technical trainer for Sun Educational Services, where my classes included DTrace, another tracing tool similar to BPF tracing. I learned firsthand how to bring beginners from different backgrounds up to speed. Early courses covered only the DTrace language, and expected students to figure out what to do with it. I found it was more effective to teach by example: explain the goals and targets of performance analysis, and then share real tools to meet those goals, and how to develop new ones. I’ve followed this proven approach in my book.

I’ve taken a break from training, but I have an opportunity to start again at Netflix, and I’ll be using this book as materials for an internal BPF course. This course will be internal only: you’ll need to join Netflix to attend my class! (Although I’ll submit a short version for USENIX LISA/SREcon.)

bpftrace for the Win

We (the BPF community) began planning this book in 2017, and posted an announcement about it so that anyone looking could find it. At the time, BCC was great for complex tools, but it was still in development and changing. Also, no higher-level front end had been completed, but we knew we needed one beyond BCC. Since then, BCC has largely stabilized, and bpftrace has become a mature high-level front-end: one that is built from the ground up for BPF. bpftrace is already in use for production analysis at companies including Netflix, Facebook, and Shopify. It allows tool source to be so short and concise it can be included in the book in its entirety. It’s like including pseudocode that you can run.

The last nine months have been hectic as I and others have added features to bpftrace, fixed bugs, and stabilized the API. The analysis of so many things unearthed many bugs and missing parts; fixing these was good not only for the book, but also for bpftrace. A special thanks to Mary Marchini, Willian Gasper, Alastair Robertson, Dale Hamel, Dan Xu, Augusto Mecking Caringi, and others, for all their work in these months. I’m also grateful that my fiancГ©e, DeirdrГ© Straughan, could find the time outside of her AWS job to do technical copy-edit. Thanks also to Alastair Robertson for creating bpftrace, Alexei Starovoitov and Daniel Borkmann for creating eBPF, and over forty other people involved in reviewing and contributing to this book.

A New Era for Linux Observability

As you’ll see, this book is the start of a new era for Linux observability: the power to easily see anything and everything, in production. A time where you can pose arbitrary questions of the system, and it can answer them. A time where you are free to think about performance in new ways, and you can fetch hard data to support or disprove your new ideas.

Isn’t BPF still evolving?

It is, but I had a static goal for the book: to get all of the included 150+ tracing tools to work. After many months of development, we’ve reached that milestone. I also involved the main BPF developers so I could document their planned work, to make this book as future-proof as possible.

BPF Type Format (BTF) is the only large change expected for tracing in the nearish future. It will provide kernel struct information beyond the linux-headers package, and is summarized in the book. A few of the tools declare missing structs as a workaround, and some years from now it will be possible to remove those workarounds.

What I expect to break sooner is the kprobe-based source code in the book. kprobes is considered an unstable API as it instruments kernel functions, and a kernel engineer may rename a function in a later kernel, breaking the tool. This is why the tools use the stable tracepoint interface whenever possible. But it’s not always possible, and this is the nature of tracing. This is not, however, the hardest problem you’ll face. The hardest problem is knowing what to do with BPF tracing, and even broken tools are a source of useful ideas. I will create a GitHub repository for the book tools as-is plus updated versions, and allow everyone to submit updates as they are found to be needed.

What about Systems Performance?

Systems Performance has sold very well (thanks, everyone!). It’s recommended reading for new hires at several companies, including some teams at Facebook and SUSE. It is the encyclopedia of performance, covering many topics with a balance of theory and practice. BPF Performance Tools focuses on one topic only – observability – and goes deeper. The BPF book is about doing analysis right now, with these tools and capabilities. Now that I’ve finished it, I can do a second edition of Systems Performance (not right away…).

Good Luck

BPF is the hot new technology, and it is an extreme privilege to have written the book on it. I was determined to give you the best book imaginable, and not waste this opportunity. I hope you enjoy it, and it helps you find valuable performance wins. Good luck!

For URLs where to find the book and updates, please see my website BPF Performance Tools (book).

You can comment here, but I can’t guarantee your comment will remain here forever: I might switch comment systems at some point (e.g., if disqus add advertisements).

Site Navigation

Systems Performance 2nd Ed.

BPF Performance Tools book

I’m speaking at AWS re:Invent 2019 —>

Recent posts:

- 26 Sep 2021 »

The Speed of Time - 06 Sep 2021 »

ZFS Is Mysteriously Eating My CPU - 30 Aug 2021 »

Analyzing a High Rate of Paging - 27 Aug 2021 »

Slack’s Secret STDERR Messages - 05 Jul 2021 »

USENIX LISA2021 Computing Performance: On the Horizon - 03 Jul 2021 »

How To Add eBPF Observability To Your Product - 15 Jun 2021 »

USENIX LISA2021 BPF Internals (eBPF) - 04 Jun 2021 »

An Unbelievable Demo - 29 May 2021 »

Moving my US tech job to Australia - 23 May 2021 »

What is Observability - 09 May 2021 »

Poor Disk Performance - 04 Nov 2020 »

BPF binaries: BTF, CO-RE, and the future of BPF perf tools - 15 Jul 2020 »

Systems Performance: Enterprise and the Cloud, 2nd Edition - 08 Mar 2020 »

LISA2019 Linux Systems Performance - 22 Dec 2019 »

BPF Theremin, Tetris, and Typewriters - 02 Dec 2019 »

BPF: A New Type of Software - 15 Oct 2019 »

Two kernel mysteries and the most technical talk I’ve ever seen - 19 Aug 2019 »

A thorough introduction to bpftrace - 15 Jul 2019 »

BPF Performance Tools: Linux System and Application Observability (book) - 26 Apr 2019 »

YOW! 2018 Cloud Performance Root Cause Analysis at Netflix

Blog index

About

RSS

I am program co-chair for LISA 2018 —>

Источник

Linux observability with bpf pdf

Linux Observability with BPF code examples

This is the companion code repo for the book Linux Observability with BPF.

We believe that even if the examples included in the book were all tested and working when we wrote them, human error is possible and technology changes. For that reason, the purpose of this repo is to keep them as updated as possible and correct mistakes we made while writing the book.

Nota Bene: All the examples in this repository are adapted from the book to assume that you use the Vagrant environment we provide. Examples can be slightly different in this repository because of that. The reason is that we didn’t want to couple the book itself to Vagrant as a tool. If you don’t want a Vagrant based environment, make sure you have: bcc and clang

- Please expand the details of the environment you want to work on.

- Remember that the examples have been tested on the Vagrant based environment primarily.

- Feel free to open an issue or a PR if you want to help in making this better for everyone!

Fedora 30

First, we need to install some build dependencies and all the tools needed for the examples:

Then we need grab a copy of the source code of the current kernel.

In our case the kernel runing can be verified with uname .

Given that version, please notice the URL we fetch the sources from in the following command. Change it according to your version.

Now that we have the kernel source, we can move it to the /kernel-src folder.

NOTE THAT: All the examples using kernel sources in this repo assume that the kernel sources are available there. In case you don’t like it, make sure you do a search and replace!

At this point we move the kernel sources and compile libbpf . Again please notice the 5.0.9 here and change accordingly.

First, we need to install some build dependencies and all the tools needed for the examples:

Note on Kernel version: make sure to have a recent kernel to run the examples, a version >=5.0.0 will do the job. Most Ubuntu 18.04 providers are shipping with the kernel 4.15 that doesn’t work for most of the examples. Upgrading options are left to the reader, we’ve been successful on aws by installing the linux-image-5.0.0-1019-aws package.

After dependencies, we need grab a copy of the kernel source code for the current release. Since this assumes that you are running an updated Ubuntu 18.04 we can get it directly from the repo they provide.

Now that we have the kernel source, we can move it to the /kernel-src folder.

NOTE THAT: All the examples using kernel sources in this repo assume that the kernel sources are available at /kernel-src . In case you don’t like it, make sure you do a search and replace!

At this point we move the kernel sources and compile libbpf .

Ubuntu doesn’t have the library path that the makefile expects so we need to move our libraries to its library path now.

The environment is based on Fedora 30.

To install Vagrant, follow the official guide here.

Once you have Vagrant installed, you will need to clone this repository and issue a vagrant up .

This Vagrant command, will start a Fedora 30 VM in Virtualbox, you can SSH into the machine using:

Before going on, make sure you download the kernel source tree in this repository. It is needed as a dependency for some examples. We will be downloading the code for Kernel 5.0.9 — We are avoiding a git clone here because the Git history of the kernel is very big.

At this point, we need to compile the libbpf library:

Before going to the examples, it will be useful to have a copy of this repo in your environment.

IMPORTANT NOTE: The examples assume that you clone the repo in your home folder

/linux-observability-with-bpf , if you didn’t do please remember to change your commands!

Yay, at this point you have everything and can follow the following code examples.

Click on each example to follow the setup instructions.

Источник