- Find Current Working Directory Of A Process Using Pwdx In Linux

- Find Current Working Directory Of A Process Using Pwdx In Linux

- Find current working directory of a Linux process using ls, lsof and readlink commands

- Discover the possibilities of the /proc directory

- /proc directory organization

- What’s in a process?

- Tweaking the system: /proc/sys

- Conclusion

- Изучаем процессы в Linux

- Содержание

- Введение

- Атрибуты процесса

- Жизненный цикл процесса

- Рождение процесса

- Состояние «готов»

- Состояние «выполняется»

- Перерождение в другую программу

- Состояние «ожидает»

- Состояние «остановлен»

- Завершение процесса

- Состояние «зомби»

- Забытье

- Благодарности

Find Current Working Directory Of A Process Using Pwdx In Linux

You are aware of «pwd» command, aren’t you? The pwd command (stands for Present Working Directory) is used to print the current working directory. What about «pwdx»? Have you ever used or heard of it? No? No problem! The pwdx command is to used report current working directory of a process. In this guide, we will see how to find current working directory of a process using pwdx command in Linux.

Find Current Working Directory Of A Process Using Pwdx In Linux

The general usage of pwdx command is given below:

For the purpose of this guide, we will find the working directory of the firefox process.

First, we need to find the process ID of the the firefox. To do so, use «ps» command like below:

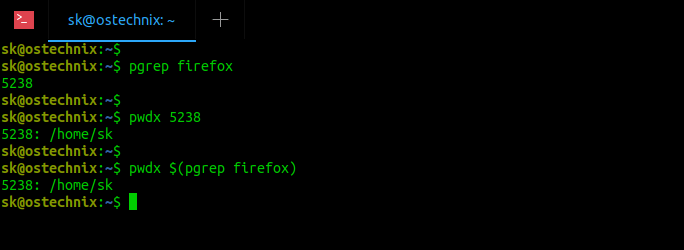

The PID of firefox is 5238. Now, find out the working directory of the PID 5238 like below:

Sample output:

Alternatively, you can combine both commands as a single command and find the current working directory of the firefox process like below:

As you can see, the current working directory of firefox process is /home/sk. This way we can easily find out on which directory a process is currently running! Please note that these commands doesn’t display where a process was invoked from, only where it currently is.

If you want to print the current directory of multiple processes, mention the PIDs with space-separated like below:

For more details, refer man pages.

Find current working directory of a Linux process using ls, lsof and readlink commands

If pwdx is not available for any reason, the following commands can get you the working directory of Linux processes:

First, find the PID of the process with pgrep command:

Next, find the process’s current working directory using»ls» command like below:

Here, cwd indicates current working directory.

Sample output:

To find out the current working directory of firefox process using «lsof» command, run:

Alternatively, combine both commands and get the result with the following one-liner :

Sample output:

Find out the current working directory of firefox process using «readlink» command, run:

Источник

Discover the possibilities of the /proc directory

The /proc directory is a strange beast. It doesn’t really exist, yet you can explore it. Its zero-length files are neither binary nor text, yet you can examine and display them. This special directory holds all the details about your Linux system, including its kernel, processes, and configuration parameters. By studying the /proc directory, you can learn how Linux commands work, and you can even do some administrative tasks.

Under Linux, everything is managed as a file; even devices are accessed as files (in the /dev directory). Although you might think that “normal” files are either text or binary (or possibly device or pipe files), the /proc directory contains a stranger type: virtual files. These files are listed, but don’t actually exist on disk; the operating system creates them on the fly if you try to read them.

Most virtual files always have a current timestamp, which indicates that they are constantly being kept up to date. The /proc directory itself is created every time you boot your box. You need to work as root to be able to examine the whole directory; some of the files (such as the process-related ones) are owned by the user who launched it. Although almost all the files are read-only, a few writable ones (notably in /proc/sys) allow you to change kernel parameters. (Of course, you must be careful if you do this.)

/proc directory organization

The /proc directory is organized in virtual directories and subdirectories, and it groups files by similar topic. Working as root, the ls /proc command brings up something like this:

/proc resources

Finding documentation about the /proc filesystem can be a chore, because it’s distributed all around the kernel source. Looking in the /usr/scr/linux/Documentation directory, I found proc.txt, which contains plenty of information but is somewhat dated: its latest update was in November 2000, when kernel version 2.4.0 was just about to come out. Still, wading through this directory is easier than looking at the C source files. Note that you might end up getting more than you wanted; for example, the laptop-mode.txt file is almost 1,000 lines long and deals exclusively with the single /proc/sys/vm/laptop_mode file.

The numbered directories (more on them later) correspond to each running process; a special self symlink points to the current process. Some virtual files provide hardware information, such as /proc/cpuinfo, /proc/meminfo, and /proc/interrupts. Others give file-related info, such as /proc/filesystems or /proc/partitions. The files under /proc/sys are related to kernel configuration parameters, as we’ll see.

The cat /proc/meminfo command might bring up something like this:

If you try the top or free commands, you might recognize some of these numbers. In fact, several well-known utilities access the /proc directory to get their information. For example, if you want to know what kernel you’re running, you might try uname -srv , or go to the source and type cat /proc/version . Some other interesting files include:

- /proc/apm: Provides information on Advanced Power Management, if it’s installed.

- /proc/acpi: A similar directory that offers plenty of data on the more modern Advanced Configuration and Power Interface. For example, to see if your laptop is connected to the AC power, you can use cat /proc/acpi/ac_adapter/AC/state to get either “on line” or “off line.”

- /proc/cmdline: Shows the parameters that were passed to the kernel at boot time. In my case, it contains root=/dev/disk/by-id/scsi-SATA_FUJITSU_MHS2040_NLA5T3314DW3-part3 vga=0x317 resume=/dev/sda2 splash=silent PROFILE=QuintaWiFi , which tells me which partition is the root of the filesystem, which VGA mode to use, and more. The last parameter has to do with openSUSE’s System Configuration Profile Management.

- /proc/cpuinfo: Provides data on the processor of your box. For example, in my laptop, cat /proc/cpuinfo gets me a listing that starts with:

This shows that I have only one processor, numbered 0, of the 80686 family (the 6 in cpu family goes as the middle digit): an AMD Athlon XP, running at less than 1GHz.

The first column shows whether the filesystem is mounted on a block device. In my case, I have partitions configured with ext2 and ext3 mounted.

There are also several RAM-related files. I’ve already mentioned /proc/meminfo, but you’ve also got /proc/iomem, which shows you how RAM memory is used in your box, and /proc/kcore, which represents the physical RAM of your box. Unlike most other virtual files, /proc/kcore shows a size that’s equal to your RAM plus a small overhead. (Don’t try to cat this file, because its contents are binary and will mess up your screen.) Finally, there are many hardware-related files and directories, such as /proc/interrupts and /proc/irq, /proc/pci (all PCI devices), /proc/bus, and so on, but they include very specific information, which most users won’t need.

What’s in a process?

As I said, the numerical named directories represent all running processes. When a process ends, its /proc directory disappears automatically. If you check any of these directories while they exist, you will find plenty of files, such as:

Let’s take a look at the principal files:

- cmdline: Contains the command that started the process, with all its parameters.

- cwd: A symlink to the current working directory (CWD) for the process; exe links to the process executable, and root links to its root directory.

- environ: Shows all environment variables for the process.

- fd: Contains all file descriptors for a process, showing which files or devices it is using.

- maps, statm, and mem: Deal with the memory in use by the process.

- stat and status: Provide information about the status of the process, but the latter is far clearer than the former.

These files provide several script programming challenges. For example, if you want to hunt for zombie processes, you could scan all numbered directories and check whether “(Z) Zombie” appears in the /status file. I once needed to check whether a certain program was running; I did a scan and looked at the /cmdline files instead, searching for the desired string. (You can also do this by working with the output of the ps command, but that’s not the point here.) And if you want to program a better-looking top , all the needed information is right at your fingertips.

Tweaking the system: /proc/sys

/proc/sys not only provides information about the system, it also allows you to change kernel parameters on the fly, and enable or disable features. (Of course, this could prove harmful to your system — consider yourself warned!)

To determine whether you can configure a file or if it’s just read-only, use ls -ld ; if a file has the “W” attribute, it means you may use it to configure the kernel somehow. For example, ls -ld /proc/kernel/* starts like this:

You can see that bootloader_type isn’t meant to be changed, but other files are. To change a file, use something like echo 10 >/proc/sys/vm/swappiness . This particular example would allow you to tune the virtual memory paging performance. By the way, these changes are only temporary, and their effects will disappear when you reboot your system; use sysctl and the /etc/sysctl.conf file to effect more permanent changes.

Let’s take a high-level look at the /proc/sys directories:

- debug: Has (surprise!) debugging information. This is good if you’re into kernel development.

- dev: Provides parameters for specific devices on your system; for example, check the /dev/cdrom directory.

- fs: Offers data on every possible aspect of the filesystem.

- kernel: Lets you affect the kernel configuration and operation directly.

- net: Lets you control network-related matters. Be careful, because messing with this can make you lose connectivity!

- vm: Deals with the VM subsystem.

Conclusion

The /proc special directory provides full detailed information about the inner workings of Linux and lets you fine-tune many aspects of its configuration. If you spend some time learning all the possibilities of this directory, you’ll be able to get a more perfect Linux box. And isn’t that something we all want?

Источник

Изучаем процессы в Linux

В этой статье я хотел бы рассказать о том, какой жизненный путь проходят процессы в семействе ОС Linux. В теории и на примерах я рассмотрю как процессы рождаются и умирают, немного расскажу о механике системных вызовов и сигналов.

Данная статья в большей мере рассчитана на новичков в системном программировании и тех, кто просто хочет узнать немного больше о том, как работают процессы в Linux.

Всё написанное ниже справедливо к Debian Linux с ядром 4.15.0.

Содержание

Введение

Системное программное обеспечение взаимодействует с ядром системы посредством специальных функций — системных вызовов. В редких случаях существует альтернативный API, например, procfs или sysfs, выполненные в виде виртуальных файловых систем.

Атрибуты процесса

Процесс в ядре представляется просто как структура с множеством полей (определение структуры можно прочитать здесь).

Но так как статья посвящена системному программированию, а не разработке ядра, то несколько абстрагируемся и просто акцентируем внимание на важных для нас полях процесса:

- Идентификатор процесса (pid)

- Открытые файловые дескрипторы (fd)

- Обработчики сигналов (signal handler)

- Текущий рабочий каталог (cwd)

- Переменные окружения (environ)

- Код возврата

Жизненный цикл процесса

Рождение процесса

Только один процесс в системе рождается особенным способом — init — он порождается непосредственно ядром. Все остальные процессы появляются путём дублирования текущего процесса с помощью системного вызова fork(2) . После выполнения fork(2) получаем два практически идентичных процесса за исключением следующих пунктов:

- fork(2) возвращает родителю PID ребёнка, ребёнку возвращается 0;

- У ребёнка меняется PPID (Parent Process Id) на PID родителя.

После выполнения fork(2) все ресурсы дочернего процесса — это копия ресурсов родителя. Копировать процесс со всеми выделенными страницами памяти — дело дорогое, поэтому в ядре Linux используется технология Copy-On-Write.

Все страницы памяти родителя помечаются как read-only и становятся доступны и родителю, и ребёнку. Как только один из процессов изменяет данные на определённой странице, эта страница не изменяется, а копируется и изменяется уже копия. Оригинал при этом «отвязывается» от данного процесса. Как только read-only оригинал остаётся «привязанным» к одному процессу, странице вновь назначается статус read-write.

Состояние «готов»

Сразу после выполнения fork(2) переходит в состояние «готов».

Фактически, процесс стоит в очереди и ждёт, когда планировщик (scheduler) в ядре даст процессу выполняться на процессоре.

Состояние «выполняется»

Как только планировщик поставил процесс на выполнение, началось состояние «выполняется». Процесс может выполняться весь предложенный промежуток (квант) времени, а может уступить место другим процессам, воспользовавшись системным вывозом sched_yield .

Перерождение в другую программу

В некоторых программах реализована логика, в которой родительский процесс создает дочерний для решения какой-либо задачи. Ребёнок в данном случае решает какую-то конкретную проблему, а родитель лишь делегирует своим детям задачи. Например, веб-сервер при входящем подключении создаёт ребёнка и передаёт обработку подключения ему.

Однако, если нужно запустить другую программу, то необходимо прибегнуть к системному вызову execve(2) :

или библиотечным вызовам execl(3), execlp(3), execle(3), execv(3), execvp(3), execvpe(3) :

Все из перечисленных вызовов выполняют программу, путь до которой указан в первом аргументе. В случае успеха управление передаётся загруженной программе и в исходную уже не возвращается. При этом у загруженной программы остаются все поля структуры процесса, кроме файловых дескрипторов, помеченных как O_CLOEXEC , они закроются.

Как не путаться во всех этих вызовах и выбирать нужный? Достаточно постичь логику именования:

- Все вызовы начинаются с exec

- Пятая буква определяет вид передачи аргументов:

- l обозначает list, все параметры передаются как arg1, arg2, . NULL

- v обозначает vector, все параметры передаются в нуль-терминированном массиве;

- Далее может следовать буква p, которая обозначает path. Если аргумент file начинается с символа, отличного от «/», то указанный file ищется в каталогах, перечисленных в переменной окружения PATH

- Последней может быть буква e, обозначающая environ. В таких вызовах последним аргументом идёт нуль-терминированный массив нуль-терминированных строк вида key=value — переменные окружения, которые будут переданы новой программе.

Семейство вызовов exec* позволяет запускать скрипты с правами на исполнение и начинающиеся с последовательности шебанг (#!).

Есть соглашение, которое подразумевает, что argv[0] совпадает с нулевым аргументов для функций семейства exec*. Однако, это можно нарушить.

Любопытный читатель может заметить, что в сигнатуре функции int main(int argc, char* argv[]) есть число — количество аргументов, но в семействе функций exec* ничего такого не передаётся. Почему? Потому что при запуске программы управление передаётся не сразу в main. Перед этим выполняются некоторые действия, определённые glibc, в том числе подсчёт argc.

Состояние «ожидает»

Некоторые системные вызовы могут выполняться долго, например, ввод-вывод. В таких случаях процесс переходит в состояние «ожидает». Как только системный вызов будет выполнен, ядро переведёт процесс в состояние «готов».

В Linux так же существует состояние «ожидает», в котором процесс не реагирует на сигналы прерывания. В этом состоянии процесс становится «неубиваемым», а все пришедшие сигналы встают в очередь до тех пор, пока процесс не выйдет из этого состояния.

Ядро само выбирает, в какое из состояний перевести процесс. Чаще всего в состояние «ожидает (без прерываний)» попадают процессы, которые запрашивают ввод-вывод. Особенно заметно это при использовании удалённого диска (NFS) с не очень быстрым интернетом.

Состояние «остановлен»

В любой момент можно приостановить выполнение процесса, отправив ему сигнал SIGSTOP. Процесс перейдёт в состояние «остановлен» и будет находиться там до тех пор, пока ему не придёт сигнал продолжать работу (SIGCONT) или умереть (SIGKILL). Остальные сигналы будут поставлены в очередь.

Завершение процесса

Ни одна программа не умеет завершаться сама. Они могут лишь попросить систему об этом с помощью системного вызова _exit или быть завершенными системой из-за ошибки. Даже когда возвращаешь число из main() , всё равно неявно вызывается _exit .

Хотя аргумент системного вызова принимает значение типа int, в качестве кода возврата берется лишь младший байт числа.

Состояние «зомби»

Сразу после того, как процесс завершился (неважно, корректно или нет), ядро записывает информацию о том, как завершился процесс и переводит его в состояние «зомби». Иными словами, зомби — это завершившийся процесс, но память о нём всё ещё хранится в ядре.

Более того, это второе состояние, в котором процесс может смело игнорировать сигнал SIGKILL, ведь что мертво не может умереть ещё раз.

Забытье

Код возврата и причина завершения процесса всё ещё хранится в ядре и её нужно оттуда забрать. Для этого можно воспользоваться соответствующими системными вызовами:

Вся информация о завершении процесса влезает в тип данных int. Для получения кода возврата и причины завершения программы используются макросы, описанные в man-странице waitpid(2) .

Передача argv[0] как NULL приводит к падению.

Бывают случаи, при которых родитель завершается раньше, чем ребёнок. В таких случаях родителем ребёнка станет init и он применит вызов wait(2) , когда придёт время.

После того, как родитель забрал информацию о смерти ребёнка, ядро стирает всю информацию о ребёнке, чтобы на его место вскоре пришёл другой процесс.

Благодарности

Спасибо Саше «Al» за редактуру и помощь в оформлении;

Спасибо Саше «Reisse» за понятные ответы на сложные вопросы.

Они стойко перенесли напавшее на меня вдохновение и напавший на них шквал моих вопросов.

Источник