- Long filenames or paths with spaces require quotation marks

- Symptoms

- Cause

- Resolution

- More information

- How To Fix ‘Filename Is Too Long’ Issue In Windows

- Why Is Filename Length Even An Issue In Windows?

- The Easy Fix

- The Less Easy Fixes

- Move, Delete, Or Copy Files Or Directories Using PowerShell

- Copy Directory Using Copy-Item

- Move Directory Using Move-Item

- Delete Directory Using Remove-Item

- Make Windows 10 Accept Long File Paths

- Make Windows 10 Home Accept Long File Paths

- Make Windows 10 Pro Or Enterprise Accept Long File Paths

- That’s It

- Naming Files, Paths, and Namespaces

- File and Directory Names

- Naming Conventions

- Short vs. Long Names

- Paths

- Fully Qualified vs. Relative Paths

- Maximum Path Length Limitation

- Namespaces

- Win32 File Namespaces

- Win32 Device Namespaces

- NT Namespaces

Long filenames or paths with spaces require quotation marks

This article provides a solution to an issue that occurs when you specify long filenames or paths with spaces.

Original product version: В Windows 10 — all editions, Windows Server 2012 R2

Original KB number: В 102739

Symptoms

The following error message is given when specifying long filenames or paths with spaces in Windows NT:

The system cannot find the file specified

Cause

Long filenames or paths with spaces are supported by NTFS in Windows NT. However, these filenames or directory names require quotation marks around them when they are specified in a command prompt operation. Failure to use the quotation marks results in the error message.

Resolution

Use quotation marks when specifying long filenames or paths with spaces. For example, typing the copy c:\my file name d:\my new file name command at the command prompt results in the following error message:

The system cannot find the file specified.

The correct syntax is:

The quotation marks must be used.

More information

Spaces are allowed in long filenames or paths, which can be up to 255 characters with NTFS. All operations at the command prompt involving long names with spaces, however, must be treated differently. Normally, it is an MS-DOS convention to use a space after a word to specify a parameter. The same convention is being followed in Windows NT command prompt operations even when using long filenames.

How To Fix ‘Filename Is Too Long’ Issue In Windows

There’s an easy fix and one that’s less easy

If you’ve ever seen this issue, it was probably a simple fix for you. If you’ve seen this error more than twice, then you also know that it can be a complex issue to fix sometimes.

Let’s hope you only run into the easy fix variety, but we’ll prepare you for the less easy, guaranteed to work fixes too.

Why Is Filename Length Even An Issue In Windows?

There’s a long history of filename lengths being a problem for operating systems like Windows. There was a time when you couldn’t have filenames longer than 8 characters plus a 3-character file extension. The best you could do was something like myresume.doc. This was a restriction in place by the design of the file system.

Things got better as new versions of Windows came out. We went from an old, limited, file system to something called the New Technology File System (NTFS). NTFS took us to a point where a filename could be 255 characters long, and the file path length could potentially go up to 32,767 characters. So how can we possibly have filenames that are too long?

Windows has things known as system variables. These are variables that Windows relies upon to function, because Windows will always know what the variables mean and where they are, even when we’re moving bits and bytes all over the place. The system variable MAX_PATH is the one that restricts filenames and file paths to under 260 characters.

Being a variable, you’d think we could change it. No, we should not. It would be like pulling a thread out of a sweater. As soon as one system variable changes, other system variables and components dependent on them start to unravel.

How do we fix it, then?

The Easy Fix

If you’re fortunate, you’ll get the error and know exactly what file’s name is causing the issue. Or at least where to find the file. Maybe you have a filename that looks something like:

It’s obvious who the offender is in this case. Find the file in Windows Explorer, or File Explorer as it’s called in Windows 10, click once on it, hit F2 to rename it, and change that silly filename to something more reasonable. Problem solved.

The Less Easy Fixes

It isn’t always that easy to fix this problem. Sometimes you may not be able to change the names of files or directories for whatever reason.

The following solutions will do the trick for you. They aren’t hard to do.

Move, Delete, Or Copy Files Or Directories Using PowerShell

Sometimes you get an error when trying to move, delete, or copy directories where the character count for the file path is more than 260.

Note that the words directory and folder are interchangeable. We’ll use ‘directory’ going forward. The following PowerShell cmdlets can also be used on files.

Perhaps the file path looks something like:

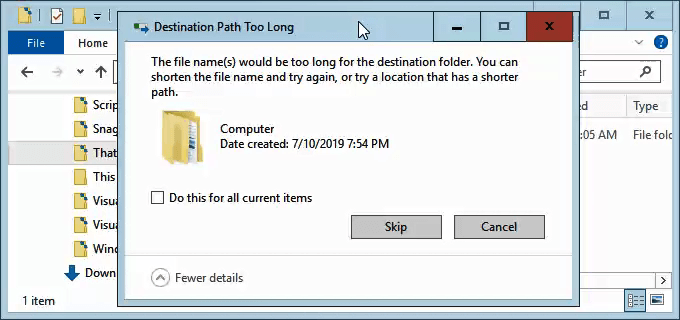

That file path is 280 characters long. So we cannot copy the directory out of there to somewhere else with the normal copy-paste method. We get the Destination Path Too Long error.

Let’s assume that for whatever reason, we can’t rename the directories in which the file is nested. What do we do?

Open PowerShell. If you haven’t used PowerShell yet, enjoy our article Using PowerShell for Home Users – A Beginner’s Guide. You can do the next steps without reading the article, though.

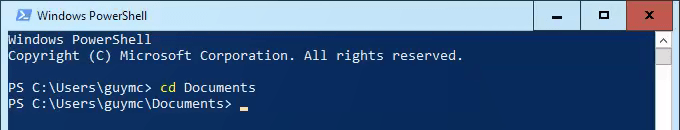

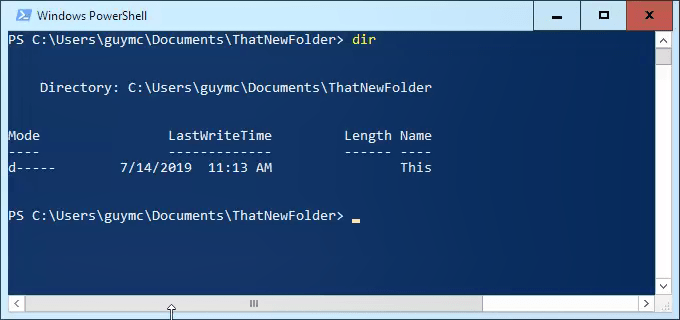

When PowerShell opens, you’ll be at the root of your user directory. Follow along assuming C:\Users\guymc is your user directory.

The directory named This is inside the Documents directory. To move into the Documents directory, we use the DOS command cd Documents.

You’ll see the prompt change to C:\Users\guymc\Documents. That’s good. We’re working closer to the directories which will make things easier.

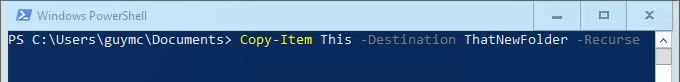

Copy Directory Using Copy-Item

We want to copy the directory This and its contents into ThatNewFolder. Let’s use the PowerShell cmdlet Copy-Item with the parameters -Destination and -Recurse.

-Destination tells PowerShell where we want the copy to be. -Recurse tells PowerShell to copy all the items inside to the destination. Copying leaves the originals where they are and makes all new ones in the destination.

Copy-Item This -Destination ThatNewFolder -Recurse

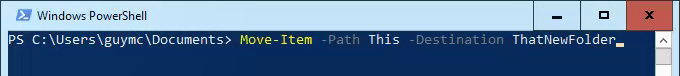

Move Directory Using Move-Item

Let’s say we want to move the directory This, and all the directories and files in it, to ThatNewFolder. Moving does not leave the original in place.

We can use the PowerShell cmdlet Move-Item with the parameters -Path and -Destination. -Path defines the item we want to move and -Destination tells PowerShell where we want it.

The cmdlet will put This inside of ThatNewFolder. It will also move everything that is inside of the This directory. Move-Item can be used to move files or directories, and it works regardless of file path or filename length.

Move-Item -Path This -Destination ThatNewFolder

To make sure it worked, use the cd ThatNewFolder command to get into ThatNewFolder. Then use the dir command to list the directories in ThatNewFolder. You’ll see the This directory is in there.

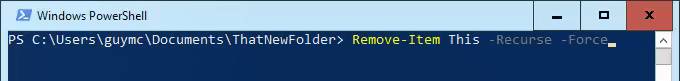

Delete Directory Using Remove-Item

If we want to delete the This directory, and everything in it, we use the Remove-Item cmdlet.

The Remove-Item cmdlet has some built-in safety that makes it difficult to delete a directory with things inside of it. In our example, we know we want to delete everything, so we’ll use the parameters -Recurse to make it delete everything inside and -Force to make it do that without asking us if we’re sure for every item inside.

Be warned! Recovering anything deleted this way would be extremely difficult. You can try the methods in How to Recover Accidentally Deleted Files, but don’t expect much.

Remove-Item This -Recurse -Force

You can use the dir command again to make sure it is gone.

Make Windows 10 Accept Long File Paths

If you know you’re going to be using long file paths and long file names repeatedly, it’s easier to make Windows work for you. No sense using PowerShell to do the work every day.

There are two ways we can do this. One is for Windows 10 Home users and the other is for Windows 10 Pro or Enterprise users. These methods may work for Windows 8.1 or earlier, but we cannot guarantee that.

Make Windows 10 Home Accept Long File Paths

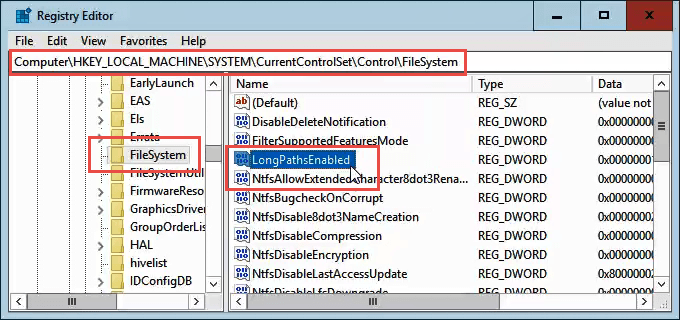

To make Windows 10 Home accept long file paths, we need to open the Registry Editor. If you haven’t worked in Registry Editor before, be cautious. Accidentally deleting or changing things in here can stop Windows from working completely.

Always make a backup of your registry before making any changes. Learn everything you need to know about that in our Ultimate Guide to Backing Up and Restoring the Windows Registry.

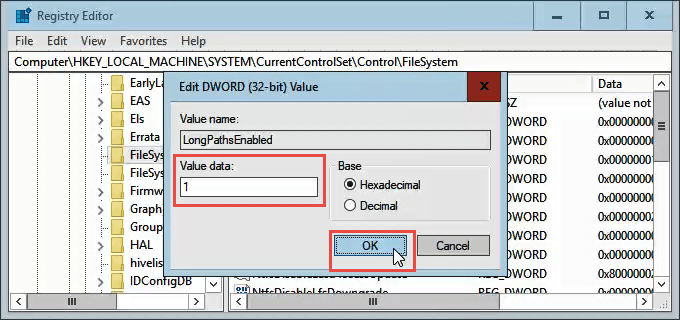

Once you have Registry Editor opened, and your backup made, navigate to the location HKEY_LOCAL_MACHINE\SYSTEM\CurrentControlSet\Control\FileSystem and find the key LongPathsEnabled.

Double-click on LongPathsEnabled. In the Value data: field, make sure the number 1 is in there. Click OK to commit the change.

Exit Registry Editor and you should be able to work with crazy long file paths now.

Make Windows 10 Pro Or Enterprise Accept Long File Paths

To allow Windows 10 Pro or Enterprise to use long file paths, we’re going to use the Group Policy Editor. It’s a tool that allows us to set policies on how Windows operates at the computer and the user levels.

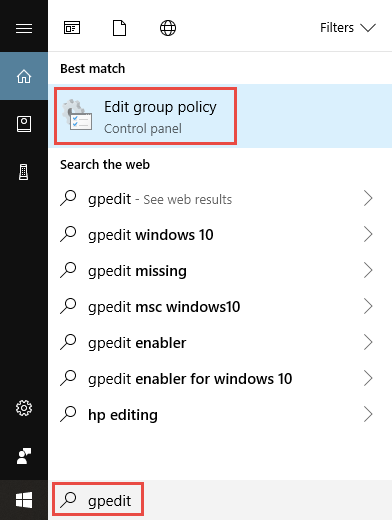

Open the Group Policy Editor by going to the Start menu and typing in gpedit. The top result should be Edit group policy. Double-click on that.

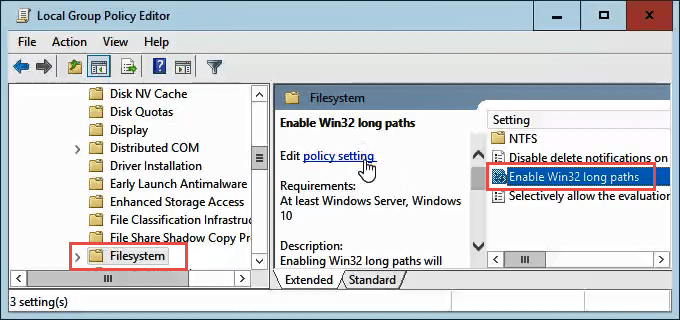

Once the Group Policy Editor opens, navigate to Computer Configuration > Administrative Templates > System > Filesystem. There you’ll see the policy Enable Win32 long paths.

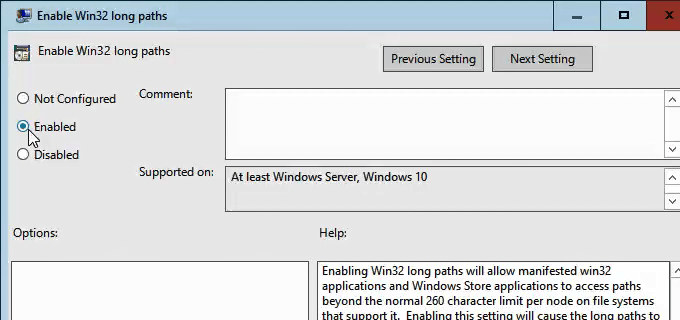

Double-click on it to edit the policy setting. Change it from Disabled to Enabled, then click the OK button to commit the change.

The policy may not take effect right away. You can force the group policy to update, though.

That’s It

There are some other ways to work around long filenames and file paths, but what we’ve gone through here are the simplest, most effective methods.

Guy has been published online and in print newspapers, nominated for writing awards, and cited in scholarly papers due to his ability to speak tech to anyone, but still prefers analog watches. Read Guy’s Full Bio

Naming Files, Paths, and Namespaces

All file systems supported by Windows use the concept of files and directories to access data stored on a disk or device. Windows developers working with the Windows APIs for file and device I/O should understand the various rules, conventions, and limitations of names for files and directories.

Data can be accessed from disks, devices, and network shares using file I/O APIs. Files and directories, along with namespaces, are part of the concept of a path, which is a string representation of where to get the data regardless if it’s from a disk or a device or a network connection for a specific operation.

Some file systems, such as NTFS, support linked files and directories, which also follow file naming conventions and rules just as a regular file or directory would. For additional information, see Hard Links and Junctions and Reparse Points and File Operations.

For additional information, see the following subsections:

To learn about configuring Windows 10 to support long file paths, see Maximum Path Length Limitation.

File and Directory Names

All file systems follow the same general naming conventions for an individual file: a base file name and an optional extension, separated by a period. However, each file system, such as NTFS, CDFS, exFAT, UDFS, FAT, and FAT32, can have specific and differing rules about the formation of the individual components in the path to a directory or file. Note that a directory is simply a file with a special attribute designating it as a directory, but otherwise must follow all the same naming rules as a regular file. Because the term directory simply refers to a special type of file as far as the file system is concerned, some reference material will use the general term file to encompass both concepts of directories and data files as such. Because of this, unless otherwise specified, any naming or usage rules or examples for a file should also apply to a directory. The term path refers to one or more directories, backslashes, and possibly a volume name. For more information, see the Paths section.

Character count limitations can also be different and can vary depending on the file system and path name prefix format used. This is further complicated by support for backward compatibility mechanisms. For example, the older MS-DOS FAT file system supports a maximum of 8 characters for the base file name and 3 characters for the extension, for a total of 12 characters including the dot separator. This is commonly known as an 8.3 file name. The Windows FAT and NTFS file systems are not limited to 8.3 file names, because they have long file name support, but they still support the 8.3 version of long file names.

Naming Conventions

The following fundamental rules enable applications to create and process valid names for files and directories, regardless of the file system:

Use a period to separate the base file name from the extension in the name of a directory or file.

Use a backslash (\) to separate the components of a path. The backslash divides the file name from the path to it, and one directory name from another directory name in a path. You cannot use a backslash in the name for the actual file or directory because it is a reserved character that separates the names into components.

Use a backslash as required as part of volume names, for example, the «C:\» in «C:\path\file» or the «\\server\share» in «\\server\share\path\file» for Universal Naming Convention (UNC) names. For more information about UNC names, see the Maximum Path Length Limitation section.

Do not assume case sensitivity. For example, consider the names OSCAR, Oscar, and oscar to be the same, even though some file systems (such as a POSIX-compliant file system) may consider them as different. Note that NTFS supports POSIX semantics for case sensitivity but this is not the default behavior. For more information, see CreateFile.

Volume designators (drive letters) are similarly case-insensitive. For example, «D:\» and «d:\» refer to the same volume.

Use any character in the current code page for a name, including Unicode characters and characters in the extended character set (128–255), except for the following:

The following reserved characters:

- (greater than)

- : (colon)

- » (double quote)

- / (forward slash)

- \ (backslash)

- | (vertical bar or pipe)

- ? (question mark)

- * (asterisk)

Integer value zero, sometimes referred to as the ASCII NUL character.

Characters whose integer representations are in the range from 1 through 31, except for alternate data streams where these characters are allowed. For more information about file streams, see File Streams.

Any other character that the target file system does not allow.

Use a period as a directory component in a path to represent the current directory, for example «.\temp.txt». For more information, see Paths.

Use two consecutive periods (..) as a directory component in a path to represent the parent of the current directory, for example «..\temp.txt». For more information, see Paths.

Do not use the following reserved names for the name of a file:

CON, PRN, AUX, NUL, COM1, COM2, COM3, COM4, COM5, COM6, COM7, COM8, COM9, LPT1, LPT2, LPT3, LPT4, LPT5, LPT6, LPT7, LPT8, and LPT9. Also avoid these names followed immediately by an extension; for example, NUL.txt is not recommended. For more information, see Namespaces.

Do not end a file or directory name with a space or a period. Although the underlying file system may support such names, the Windows shell and user interface does not. However, it is acceptable to specify a period as the first character of a name. For example, «.temp».

Short vs. Long Names

A long file name is considered to be any file name that exceeds the short MS-DOS (also called 8.3) style naming convention. When you create a long file name, Windows may also create a short 8.3 form of the name, called the 8.3 alias or short name, and store it on disk also. This 8.3 aliasing can be disabled for performance reasons either systemwide or for a specified volume, depending on the particular file system.

Windows ServerВ 2008, WindowsВ Vista, Windows ServerВ 2003 and WindowsВ XP: 8.3 aliasing cannot be disabled for specified volumes until WindowsВ 7 and Windows ServerВ 2008В R2.

On many file systems, a file name will contain a tilde (

) within each component of the name that is too long to comply with 8.3 naming rules.

Not all file systems follow the tilde substitution convention, and systems can be configured to disable 8.3 alias generation even if they normally support it. Therefore, do not make the assumption that the 8.3 alias already exists on-disk.

To request 8.3 file names, long file names, or the full path of a file from the system, consider the following options:

- To get the 8.3 form of a long file name, use the GetShortPathName function.

- To get the long file name version of a short name, use the GetLongPathName function.

- To get the full path to a file, use the GetFullPathName function.

On newer file systems, such as NTFS, exFAT, UDFS, and FAT32, Windows stores the long file names on disk in Unicode, which means that the original long file name is always preserved. This is true even if a long file name contains extended characters, regardless of the code page that is active during a disk read or write operation.

Files using long file names can be copied between NTFS file system partitions and Windows FAT file system partitions without losing any file name information. This may not be true for the older MS-DOS FAT and some types of CDFS (CD-ROM) file systems, depending on the actual file name. In this case, the short file name is substituted if possible.

Paths

The path to a specified file consists of one or more components, separated by a special character (a backslash), with each component usually being a directory name or file name, but with some notable exceptions discussed below. It is often critical to the system’s interpretation of a path what the beginning, or prefix, of the path looks like. This prefix determines the namespace the path is using, and additionally what special characters are used in which position within the path, including the last character.

If a component of a path is a file name, it must be the last component.

Each component of a path will also be constrained by the maximum length specified for a particular file system. In general, these rules fall into two categories: short and long. Note that directory names are stored by the file system as a special type of file, but naming rules for files also apply to directory names. To summarize, a path is simply the string representation of the hierarchy between all of the directories that exist for a particular file or directory name.

Fully Qualified vs. Relative Paths

For Windows API functions that manipulate files, file names can often be relative to the current directory, while some APIs require a fully qualified path. A file name is relative to the current directory if it does not begin with one of the following:

- A UNC name of any format, which always start with two backslash characters («\\»). For more information, see the next section.

- A disk designator with a backslash, for example «C:\» or «d:\».

- A single backslash, for example, «\directory» or «\file.txt». This is also referred to as an absolute path.

If a file name begins with only a disk designator but not the backslash after the colon, it is interpreted as a relative path to the current directory on the drive with the specified letter. Note that the current directory may or may not be the root directory depending on what it was set to during the most recent «change directory» operation on that disk. Examples of this format are as follows:

- «C:tmp.txt» refers to a file named «tmp.txt» in the current directory on drive C.

- «C:tempdir\tmp.txt» refers to a file in a subdirectory to the current directory on drive C.

A path is also said to be relative if it contains «double-dots»; that is, two periods together in one component of the path. This special specifier is used to denote the directory above the current directory, otherwise known as the «parent directory». Examples of this format are as follows:

- «..\tmp.txt» specifies a file named tmp.txt located in the parent of the current directory.

- «..\..\tmp.txt» specifies a file that is two directories above the current directory.

- «..\tempdir\tmp.txt» specifies a file named tmp.txt located in a directory named tempdir that is a peer directory to the current directory.

Relative paths can combine both example types, for example «C. \tmp.txt». This is useful because, although the system keeps track of the current drive along with the current directory of that drive, it also keeps track of the current directories in each of the different drive letters (if your system has more than one), regardless of which drive designator is set as the current drive.

Maximum Path Length Limitation

In editions of Windows before Windows 10 version 1607, the maximum length for a path is MAX_PATH, which is defined as 260 characters. In later versions of Windows, changing a registry key or using the Group Policy tool is required to remove the limit. See Maximum Path Length Limitation for full details.

Namespaces

There are two main categories of namespace conventions used in the Windows APIs, commonly referred to as NT namespaces and the Win32 namespaces. The NT namespace was designed to be the lowest level namespace on which other subsystems and namespaces could exist, including the Win32 subsystem and, by extension, the Win32 namespaces. POSIX is another example of a subsystem in Windows that is built on top of the NT namespace. Early versions of Windows also defined several predefined, or reserved, names for certain special devices such as communications (serial and parallel) ports and the default display console as part of what is now called the NT device namespace, and are still supported in current versions of Windows for backward compatibility.

Win32 File Namespaces

The Win32 namespace prefixing and conventions are summarized in this section and the following section, with descriptions of how they are used. Note that these examples are intended for use with the Windows API functions and do not all necessarily work with Windows shell applications such as Windows Explorer. For this reason there is a wider range of possible paths than is usually available from Windows shell applications, and Windows applications that take advantage of this can be developed using these namespace conventions.

For file I/O, the «\\?\» prefix to a path string tells the Windows APIs to disable all string parsing and to send the string that follows it straight to the file system. For example, if the file system supports large paths and file names, you can exceed the MAX_PATH limits that are otherwise enforced by the Windows APIs. For more information about the normal maximum path limitation, see the previous section Maximum Path Length Limitation.

Because it turns off automatic expansion of the path string, the «\\?\» prefix also allows the use of «..» and «.» in the path names, which can be useful if you are attempting to perform operations on a file with these otherwise reserved relative path specifiers as part of the fully qualified path.

Many but not all file I/O APIs support «\\?\»; you should look at the reference topic for each API to be sure.

Note that Unicode APIs should be used to make sure the «\\?\» prefix allows you to exceed the MAX_PATH

Win32 Device Namespaces

The «\\.\» prefix will access the Win32 device namespace instead of the Win32 file namespace. This is how access to physical disks and volumes is accomplished directly, without going through the file system, if the API supports this type of access. You can access many devices other than disks this way (using the CreateFile and DefineDosDevice functions, for example).

For example, if you want to open the system’s serial communications port 1, you can use «COM1» in the call to the CreateFile function. This works because COM1–COM9 are part of the reserved names in the NT namespace, although using the «\\.\» prefix will also work with these device names. By comparison, if you have a 100 port serial expansion board installed and want to open COM56, you cannot open it using «COM56» because there is no predefined NT namespace for COM56. You will need to open it using «\\.\COM56» because «\\.\» goes directly to the device namespace without attempting to locate a predefined alias.

Another example of using the Win32 device namespace is using the CreateFile function with «\\.\PhysicalDiskX» (where X is a valid integer value) or «\\.\CdRomX«. This allows you to access those devices directly, bypassing the file system. This works because these device names are created by the system as these devices are enumerated, and some drivers will also create other aliases in the system. For example, the device driver that implements the name «C:\» has its own namespace that also happens to be the file system.

APIs that go through the CreateFile function generally work with the «\\.\» prefix because CreateFile is the function used to open both files and devices, depending on the parameters you use.

If you’re working with Windows API functions, you should use the «\\.\» prefix to access devices only and not files.

Most APIs won’t support «\\.\»; only those that are designed to work with the device namespace will recognize it. Always check the reference topic for each API to be sure.

NT Namespaces

There are also APIs that allow the use of the NT namespace convention, but the Windows Object Manager makes that unnecessary in most cases. To illustrate, it is useful to browse the Windows namespaces in the system object browser using the Windows Sysinternals WinObj tool. When you run this tool, what you see is the NT namespace beginning at the root, or «\». The subfolder called «Global??» is where the Win32 namespace resides. Named device objects reside in the NT namespace within the «Device» subdirectory. Here you may also find Serial0 and Serial1, the device objects representing the first two COM ports if present on your system. A device object representing a volume would be something like «HarddiskVolume1», although the numeric suffix may vary. The name «DR0» under subdirectory «Harddisk0» is an example of the device object representing a disk, and so on.

To make these device objects accessible by Windows applications, the device drivers create a symbolic link (symlink) in the Win32 namespace, «Global??», to their respective device objects. For example, COM0 and COM1 under the «Global??» subdirectory are simply symlinks to Serial0 and Serial1, «C:» is a symlink to HarddiskVolume1, «Physicaldrive0» is a symlink to DR0, and so on. Without a symlink, a specified device «Xxx» will not be available to any Windows application using Win32 namespace conventions as described previously. However, a handle could be opened to that device using any APIs that support the NT namespace absolute path of the format «\Device\Xxx».

With the addition of multi-user support via Terminal Services and virtual machines, it has further become necessary to virtualize the system-wide root device within the Win32 namespace. This was accomplished by adding the symlink named «GLOBALROOT» to the Win32 namespace, which you can see in the «Global??» subdirectory of the WinObj browser tool previously discussed, and can access via the path «\\?\GLOBALROOT». This prefix ensures that the path following it looks in the true root path of the system object manager and not a session-dependent path.