- Stained Glass

- Background

- Raw Materials

- The Manufacturing Process

- Processing the stained glass

- Creating the window pattern

- Cutting and painting

- Glazing and leading

- Finishing

- Faceted glass

- The Future

- Where To Learn More

- Books

- Other

- Stained Glass Windows: Medieval Art Form and Religious Meditation

- Key Takeaways: Stained Glass

- Definition of Stained Glass

- History of Stained Glass Windows

- How to Make Stained Glass

- Gothic Window Shapes

- Medieval Cathedrals

- Medieval Meaning

- Cistercian Stained Glass (Grisailles)

- Gothic Revival and Beyond

Stained Glass

Background

The technology for making glass dates back at least 5,000 years, and some form of stained glass was used in European Christian churches by the third or fourth century A.D. The art of stained glass flowered in the 12th century with the rise of the Gothic cathedral. Today only 10% of all stained glasses are used in churches and other religious buildings; the rest are used in residential and industrial architecture. Though stained glass has traditionally been used in windows, its use has expanded to lamp shades, Christmas ornaments, and even simple objects a hobbyist can make.

Stained glass has had various levels of popularity throughout history. The 12th and 13th centuries in Europe have been designated as the Golden Age of Stained Glass. However, during the Renaissance period, stained glass was replaced with painted glass, and by the 18th century it was rarely, if ever, used or made according to medieval methods. During the second half of the 19th century, European artists rediscovered how to design and work glass according to medieval principles, and large quantities of stained glass windows were made.

In America, the stained glass movement began with William Jay Bolton, who made his first window for a church in New York in 1843. But he was to be in the business for only six or seven years before returning to his native England. No other American practiced the art professionally until Louis Comfort Tiffany and John La Farge began working with stained glass near the end of the 19th century. In fact, the art of stained glass in the United States languished until the 1870s, and did not undergo a true revival until the turn of the century. At this time, American architects and glassmen journeyed to Europe to study medieval glass windows, returning to create similar art forms and new designs in their own studios.

A leaded stained glass window or other object is made of pieces of glass, held together by lead. The pieces of glass are about 1/8-inch (3.2 mm) thick and bound together by strips, called «cames» of grooved lead, soldered at the joints. The entire window is secured in the opening at regular intervals by metal saddle bars tied with wire and soldered to the leads and reinforced at greater intervals by tee-bars fitted into the masonry. A faceted glass panel differs slightly from traditional leaded stained glass in that it is made up of pieces of slab (dalle) glass approximately 8 inches square, or in large rectangular sizes, varying in thickness from 1-2 inches (2.5-5 cm). These slabs are not held together with lead; rather they are embedded in a matrix of concrete, epoxy, or plastic.

Raw Materials

Glass is made by fusing together some form of silica such as sand, an alkali such as potash or soda, and lime or lead oxide. The color is produced by adding a metallic oxide to the raw materials.

Copper oxide, under different conditions, produces ruby, blue, or green colors in glass. Cobalt is usually used to produce most shades of blues. Green shades can also be obtained from the addition of chromium and iron oxide. Golden glass is sometimes colored with uranium, cadmium sulfide, or titanium, and there are fine selenium yellows as well as vermilions. Ruby colored glass is made by adding gold.

The Manufacturing

Process

Stained glass is still made the same way it was back in the Middle Ages and comes in various forms. For the glass used in leaded glass windows, a lump of the molten glass is caught up at one end of a blow pipe, blown into a cylinder, cut, flattened and cooled. Artisans also vary this basic process in order to produce different effects. For example, «flashed glass» is made by dipping a ball of molten white glass into molten colored glass which, when blown and flattened, results in a less intense color because it will be white on one side and colored on the other.

So-called «Norman slabs» are made by blowing the molten glass into a mold in the shape of a four-sided bottle. The sides are cut apart and form slabs, thin at the edges and as much as 0.25 inch (0.6 cm) thik) at the center. Another form of glass, known as cathedral glass, is rolled into flat sheets. This results in a somewhat monotonous regularity of texture and thickness. Other similarly made glasses are referred to as marine antique, but have a more bubbly texture.

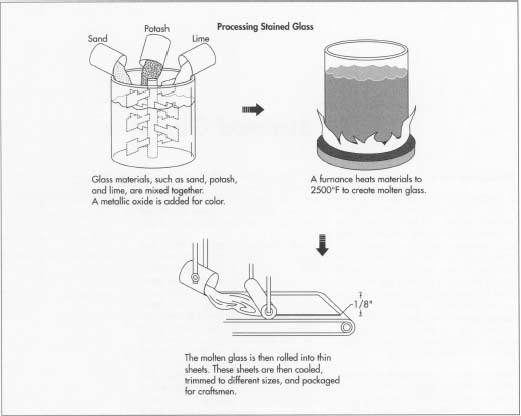

Processing the stained glass

- 1 Large manufacturers of stained glass mix the batch of raw materials, including alkaline fluxes and stabilizing agents, in huge mixers. The mix is then melted in a modern furnace at 2500°F (1371°C). Each ingredient must be carefully measured and weighed according to a calculated formula, in order to produce the appropriate color. For cathedral glass, the molten glass is ladled into a machine that rolls the glass into 1/8-inch (3.2

At a typical factory, eight to ten different color runs are made per day. Some manufacturers cut a small rectangle of glass from each run in order to provide a sample of each color to their customers. There are hundreds of colors, tints, and patterns available, as well as a number of different textures of cathedral glass. Different textures are produced by changing the roller to one having the desired texture. Glass manufacturers are continuously introducing new colors and types of glass to meet the demands of their customers.

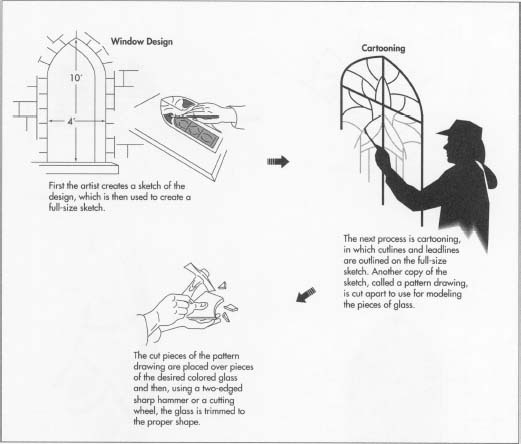

Creating the window pattern

- 2 Though some of the tools to make stained glass windows have been improved, the windows are still hand crafted as they were centuries ago. The first step of the process involves the artist creating a small scale version of the final design. After the design has been approved, the craftsperson takes measurements or templates of the actual window openings to create a pattern. This pattern is usually drawn on paper or cardboard and is the actual size of the spaces to be filled with glass.

Next a full-sized drawing called the cartoon is prepared in black and white. From the cartoon, the cutline and pattern drawings are

The pattern-drawing is a carbon copy of the cutline drawing. It is cut along the black or lead lines with double-bladed scissors or a knife which, as it passes through the middle of the black lines, simultaneously cuts away a narrow strip of paper, thus allowing sufficient space between the segment of glass for the core of the grooved lead. This core is the supporting wall between the upper and lower flanges of the lead.

Cutting and painting

- 3 Colored glass is then selected from the supply on hand. The pattern is placed on a piece of the desired color, and with a diamond or steel wheel, the glass is cut to the shape of the pattern. After the glass has been cut, the main outlines of the cartoon are painted on each piece of glass with special paint, called «vitrifiable» paint. This becomes glassy when heated. The painter might apply further paint to the glass in order to control the light and bring all the colors into closer harmony. During this painting process, the glass is held up to the light to simulate the same conditions in which the window will be seen. The painted pieces are fired in the kiln at least once to fuse the paint and glass.

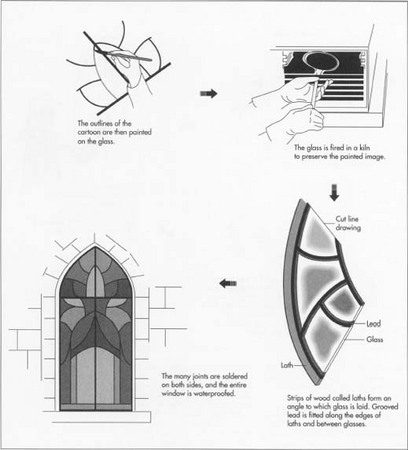

Glazing and leading

- 4 The next step is glazing. The cutline drawing is spread out on a table and narrow strips of wood called laths are nailed down along two edges of the drawing to form a right angle. Long strips of grooved lead are placed along the inside of the laths. The piece of glass belonging in the angle is fitted into the grooves. A strip of narrow lead is fitted around the exposed edge or edges and the next required segment slipped into the groove on the other side of the narrow lead. This is continued until each piece has been inserted into the leads in its proper place according to the outline drawing beneath.

Finishing

- 5 The many joints formed by the leading are then soldered on both sides and the entire window is waterproofed. After the completed window has been thoroughly inspected in the light, the sections are packed and shipped to their destination where they are installed and secured with reinforcing bars.

Faceted glass

- 6 For faceted glass windows, the process begins the same way, with the cutline and pattern drawings being made with carbons in a similar manner. The pattern drawing is then cut to the actual size of the piece of glass with ordinary scissors since there is no core of lead to allow for. The thick glass slabs next are cut with a sharp double-edged hammer to the shape of the pattern. To give the slab an interesting texture, the worker then chips round depressions in the glass with the same hammer. This is called faceting.

Instead of glazing with lead, a matrix of concrete or epoxy is poured around the pieces of glass. The glass pieces have first been glued to the outline drawing, which is covered with a heavy coating of transparent grease so that the paper can be removed after the epoxy sets. The whole is enclosed within a wooden form, which is the exact size and shape of the section being made. The worker must wear gloves during this process, since epoxy resin is a toxic material. After hardening, the section is cleaned and cured prior to shipping and installation.

The process for making an entire stained glass window can take anywhere from seven to ten weeks, since everything must be done by hand. Cost can vary widely depending on complexity and size, though some windows can be created for a cost as low as $500. The customer can choose an existing pattern rather than create an entirely new one to minimize costs. In this case, the pattern can be customized by altering shapes or by changing the placement of the central image.

The Future

In the last 20 years there has been an explosion in growth of glass studios in the United States and it appears this growth will continue. For instance, in Ohio alone the number of studios has increased from a mere half a dozen to at least 100. The Stained Glass Association of America membership includes 500 studio owners and 300 manufacturers. The circulation of its quarterly publication totals 6,000. There has been a resurgence in restoration overseas, and the home market continues to grow. The hobby market also appears strong, with one publication serving this market having a circulation of 15,000. It is clear that stained glass is now recognized as a true art form no matter where it is used, and innovative designs using this medium will continue to flourish.

Where To Learn More

Books

Clark, Willene B. The Stained Glass Art of William Jay Bolton. Syracuse University Press, 1992.

Clarke, Brian, ed. Architectural Stained Glass. McGraw-Hill, 1979.

Plowright, Terrance. Stained Glass Inspirations and Designs. Kangaroo Press, Australia, distributed by Seven Hills Book Distributors, 1993.

Other

Achilees, Rolf and Neal A. Vogel. Stained Glass in Houses of Worship. Inspired Partnerships Inc. and the National Trust for Historic Preservation, 1785 Massachusetts Avenue NW, Washington, DC 20036.

The Story of Stained Glass, 1984. The Stained Glass Association of America, PO Box 22642, Kansas City, MO 64113. 800-888-7422,816-333-6690.

Stained Glass Windows: Medieval Art Form and Religious Meditation

Print Collector / Getty Images

- M.A., Anthropology, University of Iowa

- B.Ed., Illinois State University

Stained glass is transparent colored glass formed into decorative mosaics and set into windows, primarily in churches. During the art form’s heyday, between the 12th and 17th centuries CE, stained glass depicted religious tales from the Judeo-Christian Bible or secular stories, such as Chaucer’s Canterbury tales. Some of them also featured geometric patterns in bands or abstract images often based on nature.

Making Medieval stained glass windows for Gothic architecture was dangerous work performed by guild craftsmen who combined alchemy, nano-science, and theology. One purpose of stained glass is to serve as a source of meditation, drawing the viewer into a contemplative state.

Key Takeaways: Stained Glass

- Stained glass windows combine different colors of glass in a panel to make an image.

- The earliest examples of stained glass were done for the early Christian church in the 2nd–3rd centuries CE, although none of those survived.

- The art was inspired by Roman mosaics and illuminated manuscripts.

- The heyday of Medieval religious stained glass took place between the 12th and 17th centuries.

- Abbot Suger, who lived in the 12th century and reveled in blue colors representing the «divine gloom,» is considered the father of stained glass windows.

Definition of Stained Glass

Stained glass is made of silica sand (silicon dioxide) that is super-heated until it is molten. Colors are added to the molten glass by tiny (nano-sized) amounts of minerals—gold, copper, and silver were among the earliest coloring additives for stained glass windows. Later methods involved painting enamel (glass-based paint) onto sheets of glass and then firing the painted glass in a kiln.

Stained glass windows are a deliberately dynamic art. Set into panels on exterior walls, the different colors of glass react to the sun by glowing brightly. Then, colored light spills out from the frames and onto the floor and other interior objects in shimmering, dappled pools that shift with the sun. Those characteristics attracted the artists of the Medieval period.

History of Stained Glass Windows

Glass-making was invented in Egypt about 3000 BCE—basically, glass is super-heated sand. Interest in making glass in different colors dates to about the same period. Blue in particular was a prized color in Bronze Age Mediterranean trade in ingot glass.

Putting shaped panes of differently colored glass into a framed window was first used in early Christian churches during the second or third century CE—no examples exist but there are mentions in historical documents. The art may well have been an outgrowth of Roman mosaics, designed floors in elite Roman houses that were made up of squares pieces of rock of different colors. Glass fragments were used to make wall mosaics, such as the famous mosaic at Pompeii of Alexander the Great, which was made primarily of glass fragments. There are early Christian mosaics dated to the 4th century BCE in several places throughout the Mediterranean region.

By the 7th century, stained glass was used in churches throughout Europe. Stained glass also owes a great deal to the rich tradition of illuminated manuscripts, handmade books of Christian scripture or practices, made in Western Europe between about 500–1600 CE, and often decorated in richly colored inks and gold leaf. Some of the 13th century stained glass works were copies of illuminated fables.

How to Make Stained Glass

The process of making glass is described in a few existing 12th-century texts, and modern scholars and restorers have been using those methods to replicate the process since the early 19th century.

To make a stained glass window, the artist makes a full-sized sketch or «cartoon» of the image. The glass is prepared by combining sand and potash and firing it at temperatures between 2,500–3,000°F. While still molten, the artist adds a small amount of one or more metallic oxides. Glass is naturally green, and to get clear glass, you need an additive. Some of the main mixtures were:

- Clear: manganese

- Green or blue-green: copper

- Deep blue: cobalt

- Wine-red or violet: gold

- Pale yellow to deep orange or gold: silver nitrate (called silver stain)

- Grassy green: combination of cobalt and silver stain

The stained glass is then poured into flat sheets and allowed to cool. Once cooled, the artisan lays the pieces onto the cartoon and cracks the glass in rough approximations of the shape using a hot iron. The rough edges are refined (called «grozing») by using an iron tool to chip away the excess glass until the precise shape for the composition is produced.

Next, the edges of each of the panes are covered with «cames,» strips of lead with an H-shaped cross-section; and the cames are soldered together into a panel. Once the panel is complete, the artist inserts putty between the glass and cames to aid in waterproofing. The process can take from a few weeks to many months, depending on the complexity.

Gothic Window Shapes

The most common window shapes in Gothic architecture are tall, spear-shaped «lancet» windows and circular «rose» windows. Rose or wheel windows are created in a circular pattern with panels that radiate outwards. The largest rose window is at Notre Dame Cathedral in Paris, a massive panel measuring 43 ft in diameter with 84 glass panes that radiate outward from a central medallion.

Medieval Cathedrals

The heyday of stained glass occurred in the European Middle Ages, when guilds of craftsmen produced stained glass windows for churches, monasteries, and elite households. The blossoming of the art in medieval churches is attributed to the efforts of Abbot Suger (ca. 1081–1151), a French abbot at Saint-Denis, now best known as the place where French kings were buried.

About 1137, Abbot Suger began to rebuild the church at Saint-Denis–it had been first built in the 8th century and was sorely in need of reconstruction. His earliest panel was a large wheel or rose window, made in 1137, in the choir (eastern part of the church where the singers stand, sometimes called the chancel). The St. Denis glass is remarkable for its use of blue, a deep sapphire that was paid for by a generous donor. Five windows dated to the 12th century remain, although most of the glass has been replaced.

The diaphanous sapphire blue of Abbot Suger was used in various elements of the scenes, but most significantly, it was used in backgrounds. Prior to the abbot’s innovation, backgrounds were clear, white, or a rainbow of colors. Art historian Meredith Lillich comments that for Medieval clergy, blue was next to black in the color palette, and deep blue contrasts God the «father of lights» as super-light with the rest of us in «divine gloom,» eternal darkness and eternal ignorance.

Medieval Meaning

Gothic cathedrals were transformed into a vision of heaven, a place of retreat from the noise of the city. The portrayed images were mostly of certain New Testament parables, especially the prodigal son and the good Samaritan, and of events in the life of Moses or Jesus. One common theme was the «Jesse Tree,» a genealogical form that connected Jesus as descended from the Old Testament King David.

Abbot Suger began to incorporate stained glass windows because he thought they created a «heavenly light» representing the presence of God. The attraction to the lightness in a church called for taller ceilings and larger windows: it has been argued that architects attempting to put larger windows into cathedral walls in part invented the flying buttress for that purpose. Certainly moving heavy architectural support to the exterior of the buildings opened up cathedral walls to larger window space.

Cistercian Stained Glass (Grisailles)

In the 12th century, the same stained glass images made by the same workers could be found in churches, as well as monastic and secular buildings. By the 13th century, however, the most luxurious were restricted to cathedrals.

The divide between monasteries and cathedrals was primarily of topics and style of stained glass, and that arose because of a theological dispute. Bernard of Clairvaux (known as St. Bernard, ca. 1090–1153) was a French abbot who founded the Cistercian order, a monastic offshoot of the Benedictines that was particularly critical of luxurious representations of holy images in monasteries. (Bernard is also known as the supporter of the Knights Templar, the fighting force of the Crusades.)

In his 1125 «Apologia ad Guillelmum Sancti Theoderici Abbatem» (Apology to William of St. Thierry), Bernard attacked artistic luxury, saying that what may be «excusable» in a cathedral is not appropriate to a monastery, whether cloister or church. He probably wasn’t referring particularly to stained glass: the art form didn’t become popular until after 1137. Nonetheless, the Cistercians believed that using color in images of religious figures was heretical—and Cistercian stained glass was always clear or gray («grisaille»). Cistercian windows are complex and interesting even without the color.

Gothic Revival and Beyond

The heyday of the medieval period stained glass ended about 1600, and after that it became a minor decorative or pictorial accent in architecture, with some exceptions. Beginning in the early 19th century, the Gothic Revival brought old stained glass to the attention of private collectors and museums, who sought restorers. Many small parish churches obtained medieval glasses—for example, between 1804–1811, the cathedral of Lichfield, England, obtained a vast collection of early 16th century panels from the Cistercian convent of Herkenrode.

In 1839, the Passion window of the church of St. Germain l’Auxerrois in Paris was created, a meticulously researched and executed modern window incorporating medieval style. Other artists followed, developing what they considered a rebirth of a cherished art form, and sometimes incorporating fragments of old windows as part of the principle of harmony practiced by Gothic revivalists.

Through the latter part of the 19th century, artists continued to follow a penchant for earlier medieval styles and subjects. With the art deco movement at the turn of the 20th century, artists such as Jacques Grüber were unleashed, creating masterpieces of secular glasses, a practice that still continues today.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc()/Chartres_Cathedral_Christ_Virgin-00dea391ad4f43aab86f1e80a3b9cc88.jpg)

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc()/Saint-Denis_Basilica_Paris-caad4b2be6cd4e6a99b22b23098ddf9e.jpg)

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc()/mosaic_pompeii_alexander_detail-5958d9c13df78c4eb66d797c.jpg)

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc()/Illustrated_Manuscript_13thC-dbf90d123c204f01ad31f8f582d29fbb.jpg)

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc()/stained_glass_artist-35062e8f4f96457b91effe4b03e2bf27.jpg)

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc()/Notre_Dame_Stained_Glass_Rose_Window-1e4162ed35d344fa90c052f3fe54d1cd.jpg)

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc()/Saint_Denis_Cathedral-b8fa9e0cb76e4c5cb0a64801d47cdebd.jpg)

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc()/Chartres_Cathedral_Jesse_Tree-0b593eb25b82484c9960fb3181840cee.jpg)

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc()/Eberbach_Abbey-9cd9bf57cecb4c79aa8928e0f668cafb.jpg)

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc()/St._Germain_lAuxerrois_Stained_Glass-2dd8d34a869d47a3ab115239b5ed8be5.jpg)