- Redirecting output file linux

- 3.6.1 Redirecting Input

- 3.6.2 Redirecting Output

- 3.6.3 Appending Redirected Output

- 3.6.4 Redirecting Standard Output and Standard Error

- 3.6.5 Appending Standard Output and Standard Error

- 3.6.6 Here Documents

- 3.6.7 Here Strings

- 3.6.8 Duplicating File Descriptors

- 3.6.9 Moving File Descriptors

- 3.6.10 Opening File Descriptors for Reading and Writing

- Explained: Input, Output and Error Redirection in Linux

- Stdin, stdout and stderr

- The output redirection

- The output file is created beforehand

- Append instead of clobber

- Pipe redirection

- Remember the stdout/stdin is a chunk of data, not filenames

- The input redirection

- Stderr redirection examples

- Summary

Redirecting output file linux

Before a command is executed, its input and output may be redirected using a special notation interpreted by the shell. Redirection allows commands’ file handles to be duplicated, opened, closed, made to refer to different files, and can change the files the command reads from and writes to. Redirection may also be used to modify file handles in the current shell execution environment. The following redirection operators may precede or appear anywhere within a simple command or may follow a command. Redirections are processed in the order they appear, from left to right.

Each redirection that may be preceded by a file descriptor number may instead be preceded by a word of the form < varname >. In this case, for each redirection operator except >&- and varname >. If >&- or varname >, the value of varname defines the file descriptor to close. If < varname >is supplied, the redirection persists beyond the scope of the command, allowing the shell programmer to manage the file descriptor’s lifetime manually.

In the following descriptions, if the file descriptor number is omitted, and the first character of the redirection operator is ‘ ’, the redirection refers to the standard input (file descriptor 0). If the first character of the redirection operator is ‘ > ’, the redirection refers to the standard output (file descriptor 1).

The word following the redirection operator in the following descriptions, unless otherwise noted, is subjected to brace expansion, tilde expansion, parameter expansion, command substitution, arithmetic expansion, quote removal, filename expansion, and word splitting. If it expands to more than one word, Bash reports an error.

Note that the order of redirections is significant. For example, the command

directs both standard output (file descriptor 1) and standard error (file descriptor 2) to the file dirlist , while the command

directs only the standard output to file dirlist , because the standard error was made a copy of the standard output before the standard output was redirected to dirlist .

Bash handles several filenames specially when they are used in redirections, as described in the following table. If the operating system on which Bash is running provides these special files, bash will use them; otherwise it will emulate them internally with the behavior described below.

If fd is a valid integer, file descriptor fd is duplicated.

File descriptor 0 is duplicated.

File descriptor 1 is duplicated.

File descriptor 2 is duplicated.

/dev/tcp/ host / port

If host is a valid hostname or Internet address, and port is an integer port number or service name, Bash attempts to open the corresponding TCP socket.

/dev/udp/ host / port

If host is a valid hostname or Internet address, and port is an integer port number or service name, Bash attempts to open the corresponding UDP socket.

A failure to open or create a file causes the redirection to fail.

Redirections using file descriptors greater than 9 should be used with care, as they may conflict with file descriptors the shell uses internally.

3.6.1 Redirecting Input

Redirection of input causes the file whose name results from the expansion of word to be opened for reading on file descriptor n , or the standard input (file descriptor 0) if n is not specified.

The general format for redirecting input is:

3.6.2 Redirecting Output

Redirection of output causes the file whose name results from the expansion of word to be opened for writing on file descriptor n , or the standard output (file descriptor 1) if n is not specified. If the file does not exist it is created; if it does exist it is truncated to zero size.

The general format for redirecting output is:

If the redirection operator is ‘ > ’, and the noclobber option to the set builtin has been enabled, the redirection will fail if the file whose name results from the expansion of word exists and is a regular file. If the redirection operator is ‘ >| ’, or the redirection operator is ‘ > ’ and the noclobber option is not enabled, the redirection is attempted even if the file named by word exists.

3.6.3 Appending Redirected Output

Redirection of output in this fashion causes the file whose name results from the expansion of word to be opened for appending on file descriptor n , or the standard output (file descriptor 1) if n is not specified. If the file does not exist it is created.

The general format for appending output is:

3.6.4 Redirecting Standard Output and Standard Error

This construct allows both the standard output (file descriptor 1) and the standard error output (file descriptor 2) to be redirected to the file whose name is the expansion of word .

There are two formats for redirecting standard output and standard error:

Of the two forms, the first is preferred. This is semantically equivalent to

When using the second form, word may not expand to a number or ‘ — ’. If it does, other redirection operators apply (see Duplicating File Descriptors below) for compatibility reasons.

3.6.5 Appending Standard Output and Standard Error

This construct allows both the standard output (file descriptor 1) and the standard error output (file descriptor 2) to be appended to the file whose name is the expansion of word .

The format for appending standard output and standard error is:

This is semantically equivalent to

(see Duplicating File Descriptors below).

3.6.6 Here Documents

This type of redirection instructs the shell to read input from the current source until a line containing only word (with no trailing blanks) is seen. All of the lines read up to that point are then used as the standard input (or file descriptor n if n is specified) for a command.

The format of here-documents is:

No parameter and variable expansion, command substitution, arithmetic expansion, or filename expansion is performed on word . If any part of word is quoted, the delimiter is the result of quote removal on word , and the lines in the here-document are not expanded. If word is unquoted, all lines of the here-document are subjected to parameter expansion, command substitution, and arithmetic expansion, the character sequence \newline is ignored, and ‘ \ ’ must be used to quote the characters ‘ \ ’, ‘ $ ’, and ‘ ` ’.

If the redirection operator is ‘ ’, then all leading tab characters are stripped from input lines and the line containing delimiter . This allows here-documents within shell scripts to be indented in a natural fashion.

3.6.7 Here Strings

A variant of here documents, the format is:

The word undergoes tilde expansion, parameter and variable expansion, command substitution, arithmetic expansion, and quote removal. Filename expansion and word splitting are not performed. The result is supplied as a single string, with a newline appended, to the command on its standard input (or file descriptor n if n is specified).

3.6.8 Duplicating File Descriptors

The redirection operator

is used to duplicate input file descriptors. If word expands to one or more digits, the file descriptor denoted by n is made to be a copy of that file descriptor. If the digits in word do not specify a file descriptor open for input, a redirection error occurs. If word evaluates to ‘ — ’, file descriptor n is closed. If n is not specified, the standard input (file descriptor 0) is used.

is used similarly to duplicate output file descriptors. If n is not specified, the standard output (file descriptor 1) is used. If the digits in word do not specify a file descriptor open for output, a redirection error occurs. If word evaluates to ‘ — ’, file descriptor n is closed. As a special case, if n is omitted, and word does not expand to one or more digits or ‘ — ’, the standard output and standard error are redirected as described previously.

3.6.9 Moving File Descriptors

The redirection operator

moves the file descriptor digit to file descriptor n , or the standard input (file descriptor 0) if n is not specified. digit is closed after being duplicated to n .

Similarly, the redirection operator

moves the file descriptor digit to file descriptor n , or the standard output (file descriptor 1) if n is not specified.

3.6.10 Opening File Descriptors for Reading and Writing

The redirection operator

causes the file whose name is the expansion of word to be opened for both reading and writing on file descriptor n , or on file descriptor 0 if n is not specified. If the file does not exist, it is created.

Источник

Explained: Input, Output and Error Redirection in Linux

If you are familiar with the basic Linux commands, you should also learn the concept of input output redirection.

You already know how a Linux command functions. It takes an input and gives you an output. There are a few players in the scene here. Let me tell you about them.

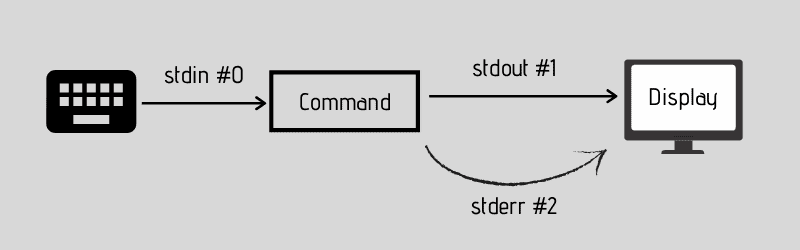

Stdin, stdout and stderr

When you run a Linux command, there are three data stream that play a part in it:

- Standard input (stdin) is the source of input data. By default, stdin is any text entered from the keyboard. It’s stream ID is 0.

- Standard output (stdout) is the outcome of command. By default, it is displayed on the screen. It’s stream ID is 1.

- Standard error (stderr) is the error message (if any) produced by the commands. By default, stderr is also displayed on the screen. It’s stream ID is 2.

These streams contain the data in plain text in what’s called buffer memory.

Think of it as water stream. You need a source for water, a tap for example. You connect a pipe to it and you can either store it in a bucket (file) or water the plants (print it). You can also connect it to another tap, if needed. Basically, you are redirecting the water.

Linux also has this concept of redirection, where you can redirect the stdin, stdout and stderr from its usual destination to another file or command (or even peripheral devices like printers).

Let me show how redirection works and how you can use it.

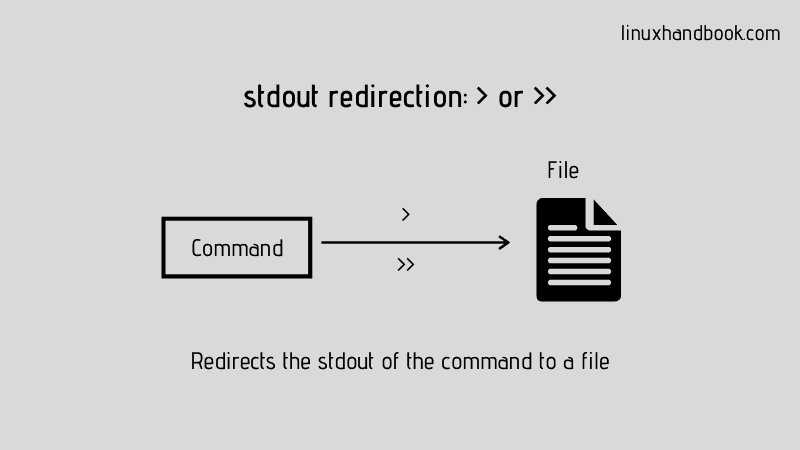

The output redirection

The first and simplest form of redirection is output redirection also called stdout redirection.

You already know that by default, the output of a command is displayed on the screen. For example, I use the ls command to list all the files and this is the output I get:

With output redirection, you can redirect the output to a file. If this output files doesn’t exist, the shell will create it.

For example, let me save the output of the ls command to a file named output.txt:

The output file is created beforehand

What do you think the content of this output file should be? Let me use the cat command to show you a surprise:

Did you notice that the inclusion of output.txt there? I deliberately chose this example to show you this.

The output file to which the stdout is redirected is created before the intended command is run. Why? Because it needs to have the output destination ready to which the output will be sent.

Append instead of clobber

One often ignored problem is that if you redirect to a file that already exists, the shell will erase (clobber) the file first. This means the existing content of the output file will be removed and replaced by the output of the command.

You can append, instead of overwriting it, using the >> redirection syntax.

Tip: You can forbid clobbering in current shell session using: set -C

Why would you redirect stdout? You can store the output for future reference and analyze it later. It is specially helpful when the command output is way too big and it takes up all of your screen. It’s like collecting logs.

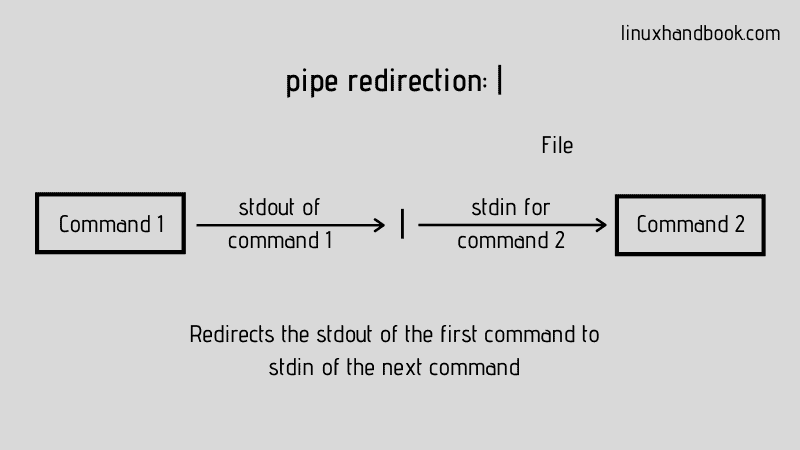

Pipe redirection

Before you see the stdin redirection, you should learn about pipe redirection. This is more common and probably you’ll be using it a lot.

With pipe redirection, you send the standard output of a command to standard input of another command.

Let me show you a practical example. Say, you want to count the number of visible files in the current directory. You can use ls -1 (it’s numeral one, not letter L) to display the files in the current directory:

You probably already know that wc command is used for counting number of lines in a file. If you combine both of these commands with pipe, here’s what you get:

With pipe, both commands share the same memory buffer. The output of the first command is stored in the buffer and the same buffer is then used as input for the next command.

You’ll see the result of the last command in the pipeline. That’s obvious because the stdout of earlier command(s) is fed to the next command(s) instead of going to the screen.

Pipe redirection or piping is not limited to connecting just two commands. You may connect more commands as long as the output of one command can be used as the input of the next command.

Remember the stdout/stdin is a chunk of data, not filenames

Some new Linux users get confused while using the redirection. If a command returns a bunch of filenames as output, you cannot use those filenames as argument.

For example, if you use the find command to find all the files ending with .txt, you cannot pass it through pipe to move the found files to a new directory, not directly like this:

This is why you’ll often see find command used in conjugation with exec or xargs command. These special commands ‘convert the text with bunch of filenames into filename’ that can be passed as argument.

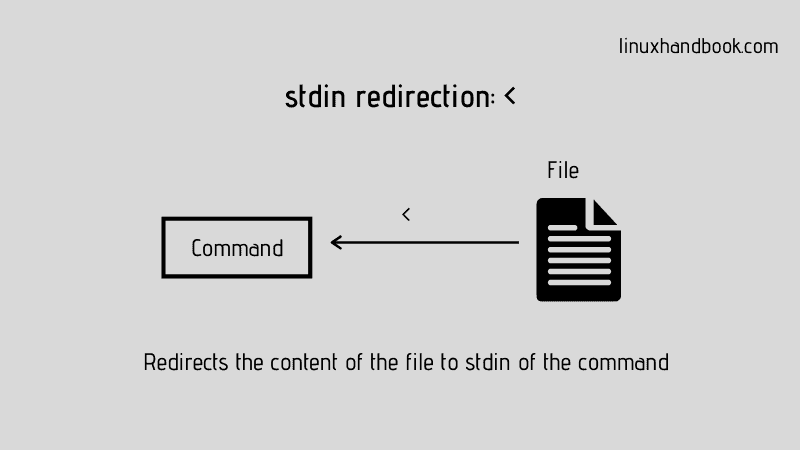

The input redirection

You can use stdin redirection to pass the content of a text file to a command like this:

You won’t see stdin being used a lot. It’s because most Linux commands accept filenames as argument and thus the stdin redirection is often not required.

Take this for example:

The above command could have just been head filename.txt (without the or >> redirection symbol that you used for stdout redirection.

But how do you distinguish between the stdout and stderr when they are both output data stream? By their stream ID (also called file descriptor).

| Data Stream | Stream ID |

|---|---|

| stdin | 0 |

| stdout | 1 |

| stderr | 2 |

| -t, | –list |

| -u, | –update |

| -x, | –extract, –get |

| -j, | –bzip2 |

| -z, | –gzip, –gunzip, –ungzip |

By default when you use the output redirection symbol >, it actually means 1>. In words, you are saying that data stream with ID 1 is being outputted here.

When you have to redirect the stderr, you use its ID like 2> or 2>>. This signifies that the output redirection is for data stream stderr (ID 2).

Stderr redirection examples

Let me show it to you with some examples. Suppose you just want to save the error, you can use something like this:

That was simple. Let’s make it slightly more complicated (and useful):

In the above example, the ls command tries to display two files. For one file it gets success and for the other, it gets error. So what I did here is to redirect the stdout to ouput.txt (with >) and the stderr to the error.txt (with 2>).

You can also redirect both stdout and stderr to the same file. There are ways to do that.

In the below example, I first send the stderr (with 2>>) to combined.txt file in append mode. And then, the stdout (with >>) is sent to the same file in append mode.

Another way, and this is the preferred one, is to use something like 2>&1. Which can be roughly translated to “redirect stderr to the same address as stdout”.

Let’s take the previous example and this time use the 2>&1 to redirect both of the stdout and stderr to the same file.

Keep in mind that you cannot use 2>>&1 thinking of using it in append mode. 2>&1 goes in append mode already.

You may also use 2> first and then use 1>&2 to redirect stdout to same file as stderr. Basically, it is “>&” which redirects one out data stream to another.

Summary

- There are three data streams. One input, stdin (0) and two output data streams stdout (1) and stderr (2).

- Keyboard is the default stdin device and the screen is the default output device.

- Output redirection is used with > or >> (for append mode).

- Input redirection is used with or 2>>.

- The stderr and stdout can be combined using 2>&1.

Since you are learning about redirection, you should also know about the tee command. This command enables you to display to standard output and save to file simultaneously.

I hope you liked this detailed guide on redirection in Linux. If you still have doubts or if you have suggestions to improve this article, please let me know in the comment section.

Источник