- How do I grep for multiple patterns with pattern having a pipe character?

- 13 Answers 13

- What is Grep Command in Linux? Why is it Used and How Does it Work?

- What is grep?

- The interesting story behind creation of grep

- What is a Regular Expression, again?

- A practical example of grep: Matching phone numbers

- Understanding regex, one segment at a time

- Pseudo-code of the Area Code RegEx

- Area Code

- Prefix

- Line Numbers

- Here’s the complete expression again

- Bonus Tip

- how to delete files have specific pattern in linux?

- 3 Answers 3

- Linux, find all files matching pattern and delete

- 4 Answers 4

- Renaming lots of files in Linux according to a pattern [closed]

- 5 Answers 5

How do I grep for multiple patterns with pattern having a pipe character?

I want to find all lines in several files that match one of two patterns. I tried to find the patterns I’m looking for by typing

but the shell interprets the | as a pipe and complains when bar isn’t an executable.

How can I grep for multiple patterns in the same set of files?

13 Answers 13

First, you need to protect the pattern from expansion by the shell. The easiest way to do that is to put single quotes around it. Single quotes prevent expansion of anything between them (including backslashes); the only thing you can’t do then is have single quotes in the pattern.

(also note the — end-of-option-marker to stop some grep implementations including GNU grep from treating a file called -foo-.txt for instance (that would be expanded by the shell from *.txt ) to be taken as an option (even though it follows a non-option argument here)).

If you do need a single quote, you can write it as ‘\» (end string literal, literal quote, open string literal).

Second, grep supports at least¹ two syntaxes for patterns. The old, default syntax (basic regular expressions) doesn’t support the alternation ( | ) operator, though some versions have it as an extension, but written with a backslash.

The portable way is to use the newer syntax, extended regular expressions. You need to pass the -E option to grep to select it (formerly that was done with the egrep separate command²)

Another possibility when you’re just looking for any of several patterns (as opposed to building a complex pattern using disjunction) is to pass multiple patterns to grep . You can do this by preceding each pattern with the -e option.

Or put patterns on several lines:

Or store those patterns in a file, one per line and run

Note that if *.txt expands to a single file, grep won’t prefix matching lines with its name like it does when there are more than one file. To work around that, with some grep implementations like GNU grep , you can use the -H option, or with any implementation, you can pass /dev/null as an extra argument.

¹ some grep implementations support even more like perl-compatible ones with -P , or augmented ones with -X , -K for ksh wildcards.

² while egrep has been deprecated by POSIX and is sometimes no longer found on some systems, on some other systems like Solaris when the POSIX or GNU utilities have not been installed, then egrep is your only option as its /bin/grep supports none of -e , -f , -E , \| or multi-line patterns

Источник

What is Grep Command in Linux? Why is it Used and How Does it Work?

If you use Linux for regular work or developing and deploying software, you must have come across the grep command.

In this explainer article, I’ll tell you what is grep command and how does it work.

What is grep?

Grep is a command line utility in Unix and Linux systems. It is used for finding a search patterns in the content of a given file.

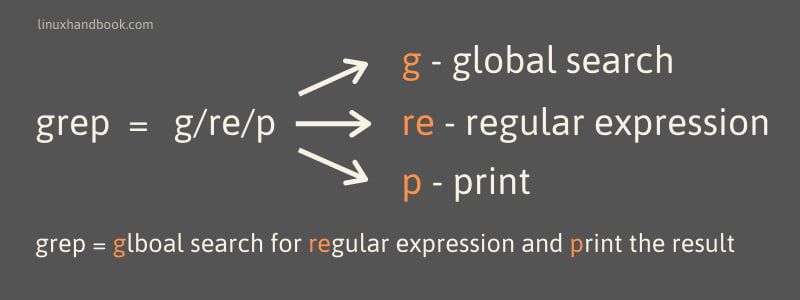

With its unusual name, you may have guessed that grep is an acronym. This is at least partially true, but it depends on who you ask.

According to reputable sources, the name is actually derived from a command in a UNIX text editor called ed. In which, the input g/re/p performed a global (g) search for a regular expression (re), and subsequently printed (p) any matching lines.

The grep command does what the g/re/p commands did in the editor. It performs a global research for a regular expression and prints it. It is much faster at searching large files.

This is the official narrative, but you may also see it described as Global Regular Expression (Processor | Parser | Printer). Truthfully, it does all of that.

The interesting story behind creation of grep

Ken Thompson has made some incredible contributions to computer science. He helped create Unix, popularized its modular approach, and wrote many of its programs including grep.

Thompson built grep to assist one of his colleagues at Bell Labs. This scientist’s goal was to examine linguistic patterns to identify the authors (including Alexander Hamilton) of the Federalist Papers. This extensive body of work was a collection of 85 anonymous articles and essays drafted in defense of the United States Constitution. But since these articles were anonymous, the scientist was trying to identify the authors based on linguistic pattern.

The original Unix text editor, ed, (also created by Thompson) wasn’t capable of searching such a large body of text given the hardware limitations of the time. So, Thompson transformed the search feature into a standalone utility, independent of the ed editor.

If you think about it, that means Alexander Hamilton technically helped create grep. Feel free to share this fun fact with your friends at your Hamilton watch party. 🤓

What is a Regular Expression, again?

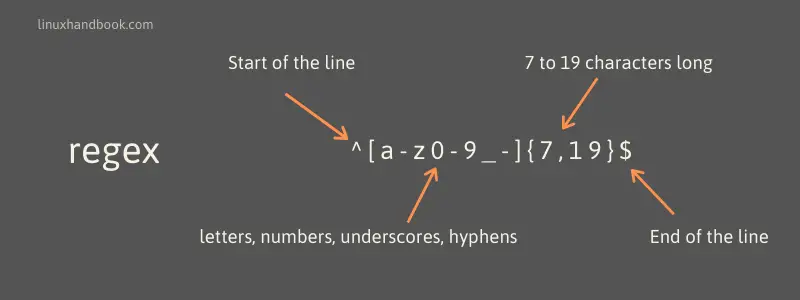

A regular expression (or regex) can be thought of as kind of like a search query. Regular expressions are used to identify, match, or otherwise manage text.

Regex is capable of much more than keyword searches, though. It can be used to find any kind of pattern imaginable. Patterns can be found easier by using meta-characters. These special characters that make this search tool much more powerful.

It should be noted that grep is just one tool that uses regex. There are similar capabilities across the range of tools, but meta characters and syntax can vary. This means it’s important to know the rules for your particular regex processor.

A practical example of grep: Matching phone numbers

This tool can be intimidating to newbies and experienced Linux users alike. Unfortunately, even a relatively simple pattern like a phone number can result in a «scary» looking regex string.

I want to reassure you that there is no need to panic when you see expressions like this. Once you become familiar with the basics of regex, it can open up a new world of possibilities for your computing.

Cultural note: This example uses US (NANP) conventions for phone numbers. These are 10-digit IDs that are broken up into an area code (3 digits), and a unique 7 digit combination where the first 3 digits correspond to a central telecom office (known as a prefix) and the last 4 are called the line number. So the pattern is AAA-PPP-LLLL.

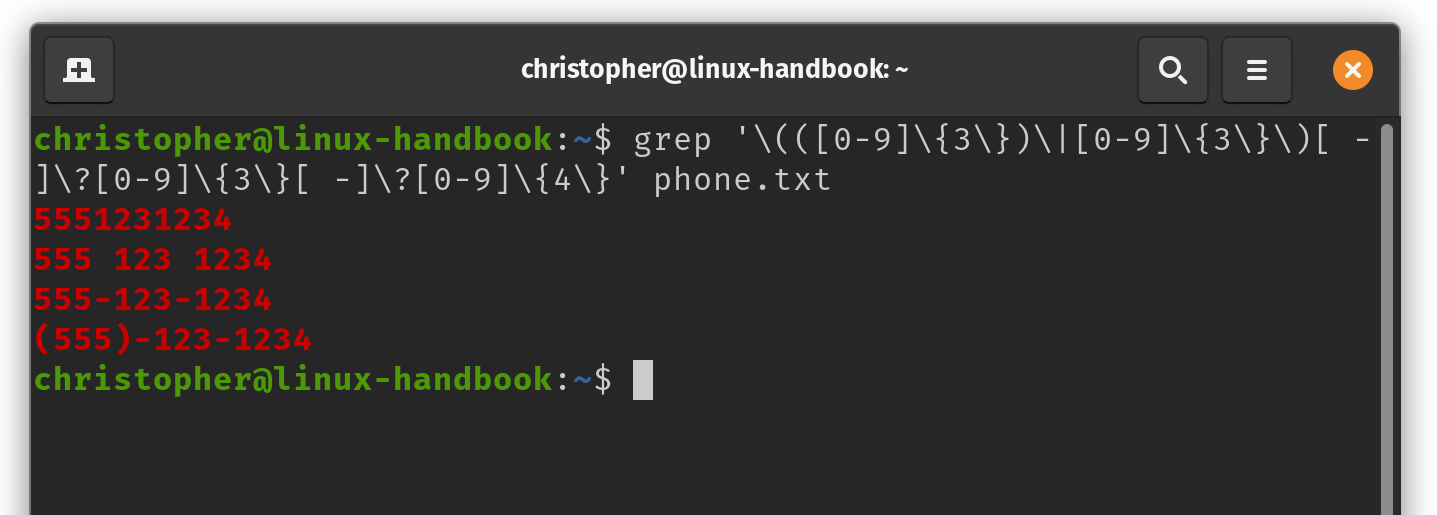

I’ve created a file called phone.txt and written down 4 common variations of the same phone number. I am going to use grep to recognize the number pattern regardless of the format.

I’ve also added one line that will not conform to the expression to use as a control. The final line 555!123!1234 is not a standard phone number pattern, and will not be returned by the grep expression.

Contents of phone.txt files are:

To «grep» the phone numbers, I am going to write my regex using meta-characters to isolate the relevant data and ignore what I don’t need.

The complete command is going to look like this:

Looks a little intense, right? Let’s break it down into chunks to get a better idea of what is happening.

Understanding regex, one segment at a time

First let’s separate the section of the RegEx that looks for the «area code» in the phone number.

A similar pattern is partially repeated to get the rest of the digits, as well. It’s important to note that the area code is sometimes encapsulated in parentheses, so you need to account for that with the expression here.

The logic of the entire area code section is encapsulated in an escaped set of round braces. You can see that my code starts with \( and ends with \) .

When you use the square brackets 9 , you’re letting grep know that you’re looking for a number between 0 and 9. Similarly, you could use [a-z] to match letters of the alphabet.

The number in the curly brackets <3\>, means that the item in the square braces is matched exactly three times.

Still confused? Don’t get stressed out. You’re going to look at this example in several ways so that you feel confident moving forward.

Let’s try looking at the logic of the area code section in pseudo-code. I’ve isolated each segment of the expression.

Pseudo-code of the Area Code RegEx

- \(

- (3-Digit Number)

- |

- 3-Digit Number

- \)

Hopefully, seeing it like this makes the regex more straightforward. In plain language you are looking for 3-digit numbers. Each digit could be 0-9, and there may or may not be parenthesis around the area code.

Then, there’s this weird bit at the end of our first section.

What does it mean? The \? symbol means «match zero or one of the preceding character». Here, that’s referring to what is in our square brackets [ -] .

In other words, there may or may not be a hyphen that follows the digits.

Area Code

Now, let’s re-build the same block with the actual code. Then, I’ll add the other parts of the expression.

Prefix

To complete the phone number pattern, you can just re-purpose some of your existing code.

You don’t have to be concerned about the parenthesis surrounding the prefix, but you still may or may not have a — between the prefix and the line digits of the phone number.

Line Numbers

The last section of the phone number does not require us to look for any other characters, but you need to update the expression to reflect the extra digit.

That’s it. Now let’s make sure that the expression is contained in quotes to minimize unexpected behaviors.

Here’s the complete expression again

You can see that the results are highlighted in color. This may not be the default behavior on your Linux distribution.

Bonus Tip

If you’d like your results to be highlighted, you could add —color=auto to your command. You could also add this to your shell profile as an alias so that every time you type grep it runs as a grep —color=auto .

I hope you have a better understand of the grep command now. I showed just one example to explain the things. If interested, you may check out this article for more practical examples of the grep command.

Do provide your suggestion on the article by leaving a comment.

Источник

how to delete files have specific pattern in linux?

I have a set of images like these

what pattern should I write to select these images and delete them

I also have these images that don’t want to select

I have tried this regex but not worked

I think bash not support regex as in Javascript, Go, Python or Java

3 Answers 3

So long as you do NOT have filenames with embedded ‘\n’ character, then the following find and grep will do:

It will find all files below the current directory and match (1 to 5 digits) followed by «-image-» followed by another (1 to 5 digits). In your case with the following files:

The files you request are matched in addition to 123-image-99999-small.jpg , e.g.

You can use the above in a command substitution to remove the files, e.g.

The remaining files are:

If Your find Supports -regextype

If your find supports the regextype allowing you to specify which set of regular expression syntax to use, you can use -regextype grep for grep syntax and use something similar to the above to remove the files with the -execdir option, e.g.

I do not know whether this is supported by BSD or Solaris, etc. so check before turning it loose in a script. Also note, [[:digit:]]\+ tests for (1 or more) digits and is not limited to 5-digits as shown in your question.

Источник

Linux, find all files matching pattern and delete

Looking to find all files (recursively) which have an underscore in their file name and then delete them via command line.

4 Answers 4

This is the safest and fastest variant:

It does not require piping and doesn’t break if files contain spaces or globbing characters or anything else that other constructs would choke on. The easiest rule to remember here is to never parse find output. And never grep on filenames if you want to do something with them later. You can do almost anything with find directly.

This includes directories which are considered files. Some of the other examples using xargs will fail if the filename contains spaces.

If you only want regular files:

Alright, let’s do this progressively.

As a first pass, this is just a simple exercise in passing a wildcard to the find command, remembering to quote it of course, and executing the rm command for every file found:

But of course that’s dreadfully inefficient. It starts up a whole rm process for each individual file. So while we could take a short detour through \+ that’s not where we are going to end up, so let’s take the shorter route and bring in xargs to batch up the filenames into groups:

But that has two security holes. First, if any filename found happens to begin with a minus sign rm will treat it as a command-line option rather than a filename, and generate an error. (The -exec rm <> version also has this problem.) Second, filenames containing whitespace will not be handled properly by xargs . So a further iteration is to make this a little more bulletproof:

And, of course, there are the interactive features of rm that you probably don’t want:

The -print0 and -0 options are not standard, but the GNU find and xargs , as well as the FreeBSD find and xargs , understand them. However, even this is improvable. We don’t need to spawn any extra processes at all. The GNU and FreeBSD find s can both invoke the unlink(2) system call directly:

As a last preventative measure to stop you doing more than you intended in certain circumstances, remember that the filesystem can contain more than just regular files:

Источник

Renaming lots of files in Linux according to a pattern [closed]

Want to improve this question? Update the question so it’s on-topic for Stack Overflow.

Closed 7 years ago .

I’m trying to do three things with the mv command, but not sure it’s possible? Probably need a script. not sure how to write it. All files are in same folder.

1) Files ending with v9.zip should just be .zip (the v9 removed)

2) Files containing _ should be —

3) Files with Uppercase letter next to a lowercase letter (or lowercase next to an Uppercase) should have a space between them. So MoveOverNow would be Move Over Now and ruNaway would be ruN away [A-Z][a-z] or [a-z][A-Z] becomes [A-Z] [a-z] and [a-z] [A-Z]

5 Answers 5

There’s a rename command provided with most Debian/Ubuntu based distros which was written by Robin Barker based on Larry Wall’s original code from around 1998(!).

Here’s an excerpt from the documentation:

It uses perl so you can use perl expressions to match the pattern, in fact I believe it works much like tchrist’s scripts.

One other really useful set of tools for bulk file renaming is the renameutils collection by Oskar Liljeblad. The source code is hosted by the Free Software Foundation. Additionally many distros (especially Debian/Ubuntu based distros) have a renameutils package with these tools.

On one of those distros you can install it with:

And then to rename files just run this command:

It will pop open a text editor with the list of files, and you can manipulate them with your editor’s search and replace function.

Источник