- How To Use Regular Expression – Regex In Bash Linux?

- Syntax

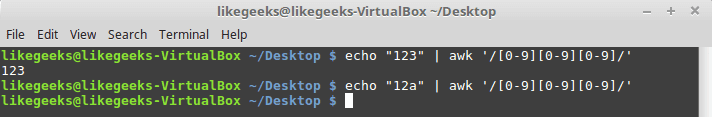

- Match Digits

- Specify Start Of Line

- Specify End Of Line

- Match Email

- Match IP Address

- Основы Linux от основателя Gentoo. Часть 2 (1/5): Регулярные выражения

- Предисловие

- Об этом самоучителе

- Регулярные выражения

- Что такое «регулярное выражение»?

- В сравнении с глоббингом

- Простая подстрока

- Понимание простой подстроки

- Метасимволы

- Использование []

- Использование [^]

- Отличающийся синтаксис

- Матасимвол *

- Начало и конец строки

- Полнострочные регулярки

- Об авторах

- Daniel Robbins

- Chris Houser

- Aron Griffis

- Regex tutorial for Linux (Sed & AWK) examples

- What is regex

- Types of regex

- Define BRE Patterns

- Special characters

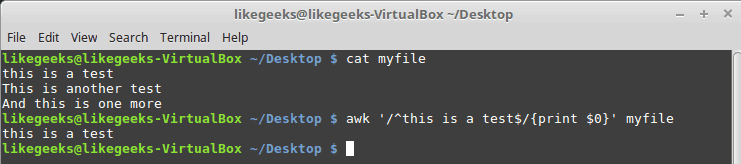

- Anchor characters

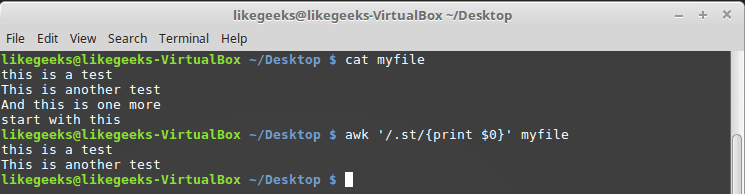

- The dot character

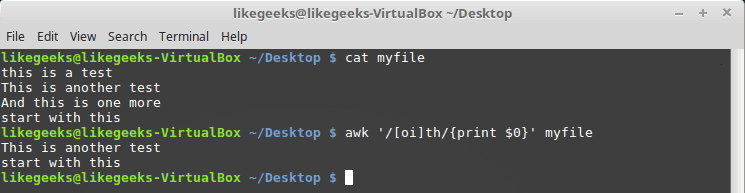

- Character classes

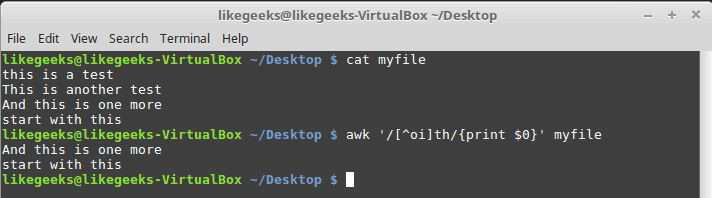

- Negating character classes

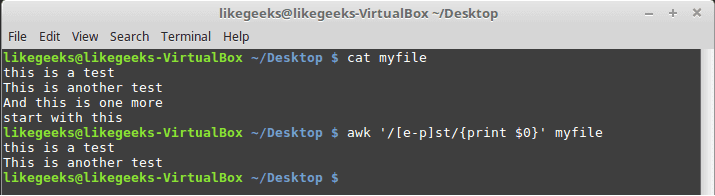

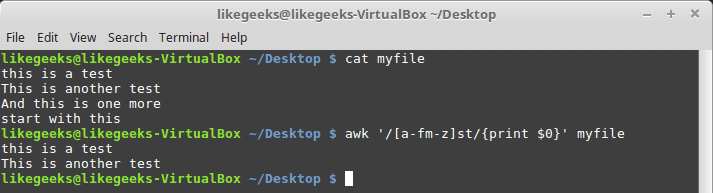

- Using ranges

- Special character classes

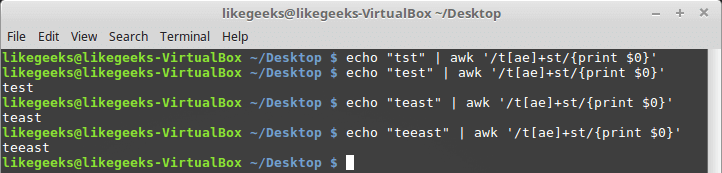

- The asterisk

- Extended regular expressions

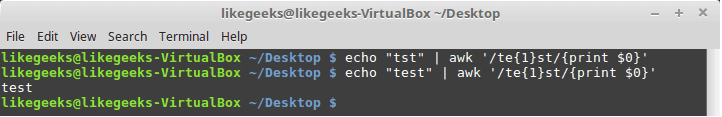

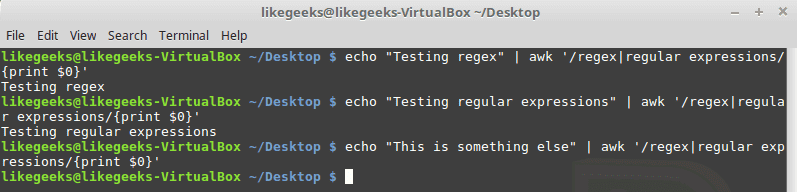

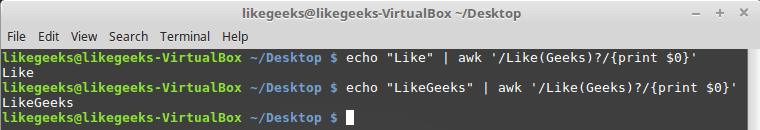

- The question mark

- The plus sign

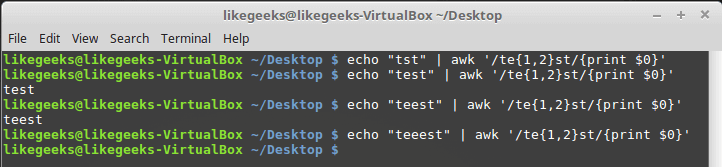

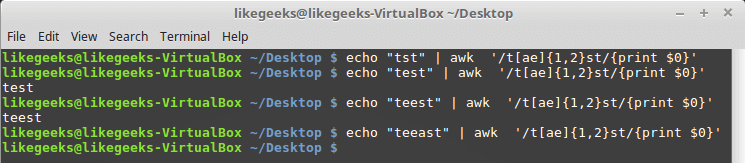

- Curly braces

- Pipe symbol

- Grouping expressions

- Practical examples

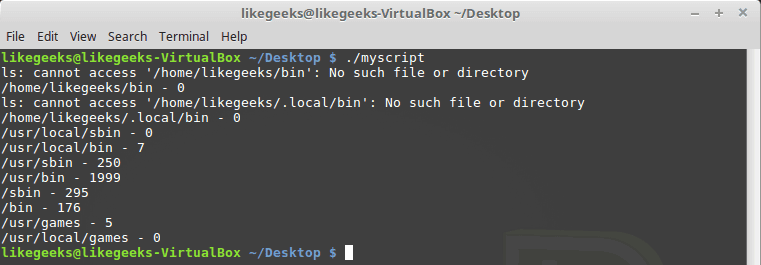

- Counting directory files

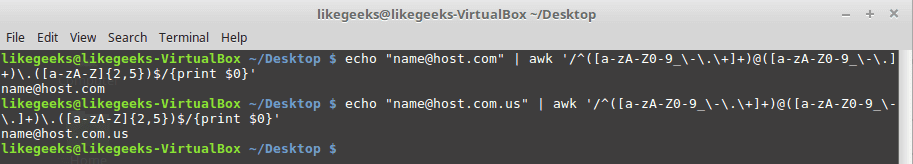

- Validating E-mail address

How To Use Regular Expression – Regex In Bash Linux?

Linux bash provides a lot of commands and features for Regular Expressions or regex. grep , expr , sed and awk are some of them. Bash also have =

operator which is named as RE-match operator. In this tutorial we will look =

operator and use cases. More information about regex command cna be found in the following tutorials.

Syntax

Syntax of the bash rematch is very easy we just provide the string and then put the operator and the last one is the regular expression we want to match. We also surround the expression with double brackets like below.

Match Digits

In daily bash shell usage we may need to match digits or numbers. We can use bash regex operator. We will state numbers with 8 like below. But keep in mind that bash regex can be fairly complicated in some cases. In this example we will simple match given line for digits

Specify Start Of Line

In previous example we have matched digits in the whole line. This is not case some times. We may need to match from start of the line with digits of other character type. We can use ^ to specify start of the line. In this example we will match line which starts with 123 . As we can see it didn’t match.

Specify End Of Line

We can also specify the end on line. We will use $ to specify end of line. We will match line which ends with any digit.

Match Email

Digit patterns are easy to express but how can we express email regex in bash. We can use following regex pattern for emails generally.

We will ommit suffixes like com , net , gov etc. because there is a lot of possibilities. As we know @ is sitting between username and domain name.

Match IP Address

IP address is another type of important data type which is used in bash and scripting. We can match IP addresses by using bash regex. We will use following regex pattern which is the same with tools like grep and others.

Источник

Основы Linux от основателя Gentoo. Часть 2 (1/5): Регулярные выражения

Предисловие

Об этом самоучителе

Добро пожаловать в «Азы администрирования», второе из четырех обучающих руководств, разработанных чтобы подготовить вас к экзамену 101 в Linux Professional Institute. В данной части мы рассмотрим как использовать регулярные выражения для поиска текста в файлах по шаблонам. Затем, вы познакомитесь со «Стандартом иерархии файловой системы» (Filesystem Hierarchy Standard или сокр. FHS), также мы покажем вам как находить нужные файлы в вашей системе. После чего, вы узнаете как получить полный контроль над процессами в Linux, запуская их в фоновом режиме, просматривая список процессов, отсоединяя их от терминала, и многое другое. Далее последует быстрое введение в конвейеры, перенаправления и команды обработки текста. И наконец, мы познакомим вас с модулями ядра Linux.

В частности эта часть самоучителя (Часть 2) идеальна для тех, кто уже имеет неплохие базовые знания bash и хочет получить качественное введение в основные задачи администрирования Linux. Если в Linux вы новичок, мы рекомендуем вам сперва закончить первую часть данной серии практических руководств. Для некоторых, большая часть данного материала будет новой, более опытные же пользователи Linux могут счесть его отличным средством подвести итог своим базовым навыкам администрирования.

Если вы изучали первый выпуск данного самоучителя с целью, отличной от подготовки к экзамену LPI, то вам, возможно, не нужно перечитывать этот выпуск. Однако, если вы планируете сдавать экзамен, то вам настоятельно рекомендуются перечитать данную, пересмотренную версию самоучителя.

Регулярные выражения

Что такое «регулярное выражение»?

Регулярное выражение (по англ. regular expression, сокр. «regexp» или «regex», в отечестве иногда зовется «регулярка» — прим. пер.) — это особый синтаксис используемый для описания текстовых шаблонов. В Linux-системах регулярные выражения широко используются для поиска в тексте по шаблону, а также для операций поиска и замены на текстовых потоках.

В сравнении с глоббингом

Как только мы начнем рассматривать регулярные выражения, возможно вы обратите внимание, что их синтаксис очень похож на синтаксис подстановки имен файлов (globbing), который мы рассматривали в первой части. Однако, не стоит заблуждаться, эта схожесть очень поверхностна. Регулярные выражения и глоббинг-шаблоны, даже когда они выглядят похоже, принципиально разные вещи.

Простая подстрока

После этого предостережения, давайте рассмотрим самое основное в регулярных выражениях, простейшую подстроку. Для этого мы воспользуемся «grep», командой, которая сканирует содержимое файла согласно заданному регулярному выражению. grep выводит каждую строчку, которая совпадает с регулярным выражением, игнорируя остальные:

Выше, первый параметр для grep, это regex; второй — имя файла. grep считывал каждую строчку из /etc/passwd и прикладывал на нее простую regex-подстроку «bash» в поисках совпадения. Если совпадение обнаруживалось, то grep выводил всю строку целиком; в противном случае, строка игнорировалась.

Понимание простой подстроки

В общем случае, если вы ищите подстроку, вы просто можете указать её буквально, не используя каких-либо «специальных» символов. Вам понадобиться особо позаботиться, только если ваша подстрока содержит +, ., *, [, ] или \, в этом случае эти символы должны быть экранированы обратным слешем, а подстрока заключаться в кавычки. Вот несколько примеров регулярных выражений в виде простой подстроки:

- /tmp (поиск строки /tmp)

- «\[box\]» (поиск строки [box])

- «\*funny\*» (поиск строки *funny*)

- «ld\.so» (поиск строки ld.so)

Метасимволы

С помощью регулярных выражений используя метасимволы возможно осуществлять гораздо более сложный поиск, чем в примерах, которые недавно рассматривали. Один из таких метасимволов «.» (точка), который совпадает с любым единичным символом:

В этом примере текст dev.sda не появляется буквально ни в одной из строчек из /etc/fstab. Однако, grep сканирует его не буквально по строке dev.sda, а по dev.sda шаблону. Запомните, что «.» будет соответствовать любому единичному символу. Как вы видите, метасимвол «.» функционально эквивалентен тому, как работает метасимвол «?» в glob-подстановках.

Использование []

Если мы хотим задать символ конкретнее, чем это делает «.», то можем использовать [ и ] (квадратные скобки), чтобы указать подмножество символов для сопоставления:

Как вы заметили, в частности, данная синтаксическая конструкция работает идентично конструкции «[]» при glob-подстановке имен файлов. Опять же, в этом заключается одна из неоднозначностей в изучении регулярных выражений: синтаксис похожий, но не идентичный синтаксису glob-подстановок, что сбивает с толку.

Использование [^]

Вы можете обратить значение квадратных скобок поместив ^ сразу после [. В этому случае скобки будут соответствовать любому символу который НЕ перечислен внутри них. И опять, заметьте что [^] мы используем с регулярными выражением, а [!] с glob:

Отличающийся синтаксис

Очень важно отметить, что синтаксис внутри квадратных скобок коренным образом отличается от остальной части регулярного выражения. К примеру, если вы поместите «.» внутрь квадратных скобок, это позволит квадратным скобкам совпадать с «.» буквально, также как 1 и 2 в примере выше. Для сравнения, «.» помещенная вне квадратных скобок, будет интерпретирована как метасимвол, если не приставить «\». Мы можем получить выгоду из данного факта для вывода строк из /etc/fstab которые содержат строку dev.sda, как она записана:

$ grep dev[.]sda /etc/fstab

Также, мы могли бы набрать:

$ grep «dev\.sda» /etc/fstab

Эти регулярные выражения вероятно не удовлетворяют ни одной строчке из вашего /etc/fstab файла.

Матасимвол *

Некоторые метасимволы сами по себе не соответствуют ничему, но изменяют значение предыдущего символа. Один из таких символов, это * (звездочка), который используется для сопоставления нулевому или большему числу повторений предшествующего символа. Заметьте, это значит, что * имеет другое значение в регулярках, нежели в глоббинге. Вот несколько примеров, и обратите особое внимание на те случаи где сопоставление регулярных выражений отличается от glob-подстановок:

- ab*c совпадает с «abbbbc», но не с «abqc» (в случае glob-подстановки, обе строчки будут удовлетворять шаблону. Вы уже поняли почему?)

- ab*c совпадает с «abc», но не с «abbqbbc» (опять же, при glob-подстановке, шаблон сопоставим с обоими строчками)

- ab*c совпадает с «ac», но не с «cba» (в случае глоббинга, ни «ac», ни «cba» не удовлетворяют шаблону)

- b[cq]*e совпадает с «bqe» и с «be» (glob-подстановке удовлетворяет «bqe», но не «be»)

- b[cq]*e совпадает с «bccqqe», но не с «bccc» (при глоббинге шаблон точно так же совпадет с первым, но не со вторым)

- b[cq]*e совпадает с «bqqcce», но не с «cqe» (так же и при glob-подстановке)

- b[cq]*e удовлетворяет «bbbeee» (но не в случае глоббинга)

- .* сопоставим с любой строкой (glob-подстановке удовлетворяют только строки начинающиеся с «.»)

- foo.* совпадет с любой подстрокой начинающийся с «foo» (в случае glob-подстановки этот шаблон будет совпадать со строками, начинающимися с четырех символов «foo.»)

Итак, повторим для закрепления: строчка «ac» подходит под регулярное выражение «ab*c» потому, что звездочка также позволяет повторение предшествующего выражения (b) ноль раз. И опять, ценно отметить для себя, что метасимвол * в регулярках интерпретируется совершенно иначе, нежели символ * в glob-подстновках.

Начало и конец строки

Последние метасимволы, что мы детально рассмотрим, это ^ и $, которые используются для сопостовления началу и концу строки, соответственно. Воспользовавшись ^ в начале вашего regex, вы «прикрепите» ваш шаблон к началу строки. В следующием примере, мы используем регулярное выражение ^#, которое удовлетворяет любой строке начинающийся с символа #:

$ grep ^# /etc/fstab

# /etc/fstab: static file system information.

#

Полнострочные регулярки

^ и $ можно комбинировать, для сопоставлений со всей строкой целиком. Например, нижеследующая регулярка будет соответсвовать строкам начинающимся с символа #, а заканчивающимся символом «.», при произвольном количестве символов между ними:

$ grep ‘^#.*\.$’ /etc/fstab

# /etc/fstab: static file system information.

В примере выше мы заключили наше регулярное выражение в одиночные кавычки, чтобы предотвратить интерпретирование символа $ командной оболочкой. Без одиночных кавычек $ исчез бы из нашей регулярки еще даже до того, как grep мог его увидеть.

Об авторах

Daniel Robbins

Дэниэль Роббинс — основатель сообщества Gentoo и создатель операционной системы Gentoo Linux. Дэниэль проживает в Нью-Мехико со свой женой Мэри и двумя энергичными дочерьми. Он также основатель и глава Funtoo, написал множество технических статей для IBM developerWorks, Intel Developer Services и C/C++ Users Journal.

Chris Houser

Крис Хаусер был сторонником UNIX c 1994 года, когда присоединился к команде администраторов университета Тэйлора (Индиана, США), где получил степень бакалавра в компьютерных науках и математике. После он работал во множестве областей, включая веб-приложения, редактирование видео, драйвера для UNIX и криптографическую защиту. В настоящий момент работает в Sentry Data Systems. Крис также сделал вклад во множество свободных проектов, таких как Gentoo Linux и Clojure, стал соавтором книги The Joy of Clojure.

Aron Griffis

Эйрон Гриффис живет на территории Бостона, где провел последнее десятилетие работая в Hewlett-Packard над такими проектами, как сетевые UNIX-драйвера для Tru64, сертификация безопасности Linux, Xen и KVM виртуализация, и самое последнее — платформа HP ePrint. В свободное от программирования время Эйрон предпочитает размыщлять над проблемами программирования катаясь на своем велосипеде, жонглируя битами, или болея за бостонскую профессиональную бейсбольную команду «Красные Носки».

Источник

Regex tutorial for Linux (Sed & AWK) examples

To successfully work with the Linux sed editor and the awk command in your shell scripts, you have to understand regular expressions or in short regex. Since there are many engines for regex, we will use the shell regex and see the bash power in working with regex.

First, we need to understand what regex is; then we will see how to use it.

Table of Contents

What is regex

For some people, when they see the regular expressions for the first time, they said what are these ASCII pukes !!

Well, A regular expression or regex, in general, is a pattern of text you define that a Linux program like sed or awk uses it to filter text.

We saw some of those patterns when introducing basic Linux commands and saw how the ls command uses wildcard characters to filter output.

Types of regex

Many different applications use different types of regex in Linux, like the regex included in programming languages (Java, Perl, Python,) and Linux programs like (sed, awk, grep,) and many other applications.

A regex pattern uses a regular expression engine that translates those patterns.

Linux has two regular expression engines:

- The Basic Regular Expression (BRE) engine.

- The Extended Regular Expression (ERE) engine.

Most Linux programs work well with BRE engine specifications, but some tools like sed understand some of the BRE engine rules.

The POSIX ERE engine comes with some programming languages. It provides more patterns, like matching digits and words. The awk command uses the ERE engine to process its regular expression patterns.

Since there are many regex implementations, it’s difficult to write patterns that work on all engines. Hence, we will focus on the most commonly found regex and demonstrate how to use it in the sed and awk.

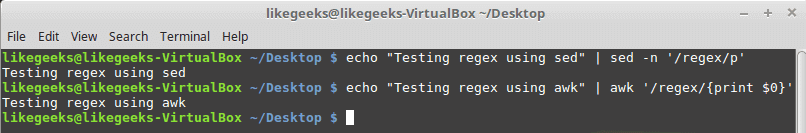

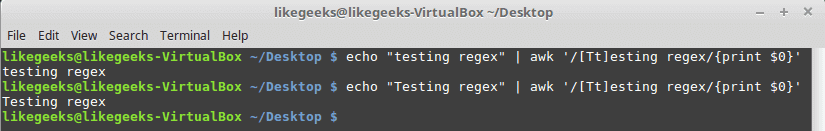

Define BRE Patterns

You can define a pattern to match text like this:

You may notice that the regex doesn’t care where the pattern occurs or how many times in the data stream.

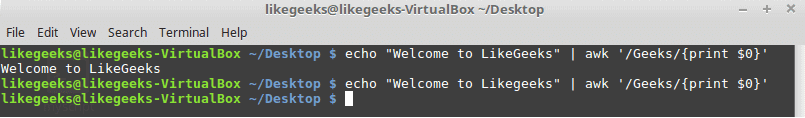

The first rule to know is that regular expression patterns are case sensitive.

The first regex succeeds because the word “Geeks” exists in the upper case, while the second line fails because it uses small letters.

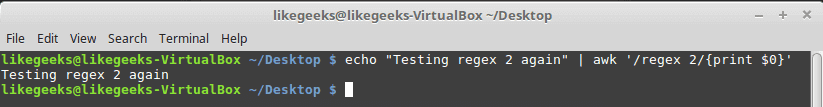

You can use spaces or numbers in your pattern like this:

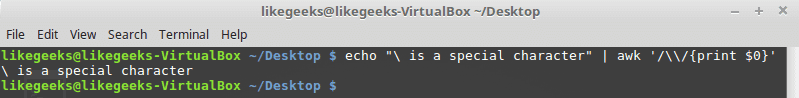

Special characters

regex patterns use some special characters. And you can’t include them in your patterns, and if you do so, you won’t get the expected result.

These special characters are recognized by regex:

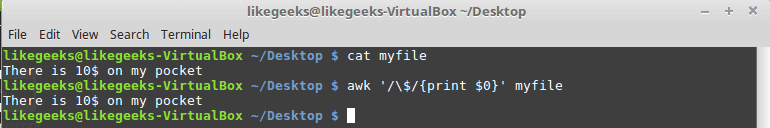

You need to escape these special characters using the backslash character (\).

For example, if you want to match a dollar sign ($), escape it with a backslash character like this:

If you need to match the backslash (\) itself, you need to escape it like this:

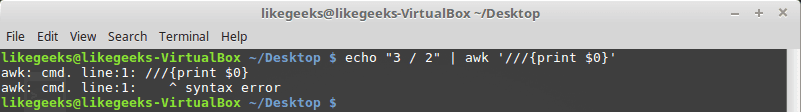

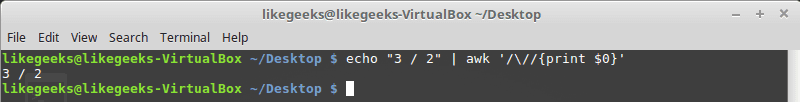

Although the forward-slash isn’t a special character, you still get an error if you use it directly.

So you need to escape it like this:

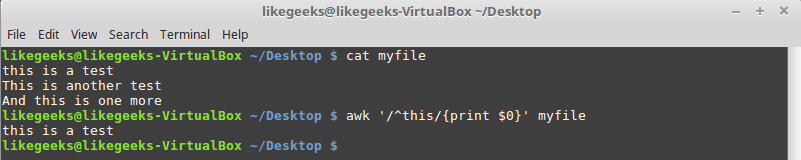

Anchor characters

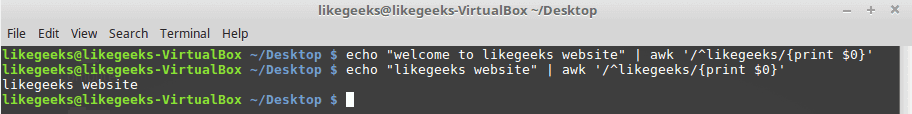

To locate the beginning of a line in a text, use the caret character (^).

You can use it like this:

The caret character (^) matches the start of the text:

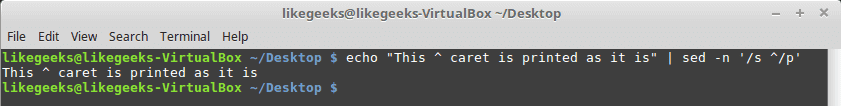

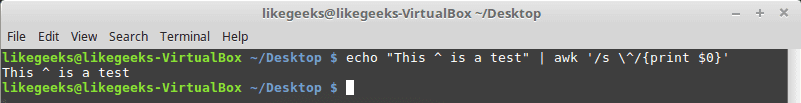

What if you use it in the middle of the text?

It’s printed as it is like a normal character.

When using awk, you have to escape it like this:

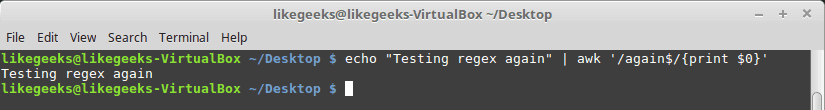

This is about looking at the beginning of the text, what about looking at the end?

The dollar sign ($) checks for the end a line:

You can use both the caret and dollar sign on the same line like this:

As you can see, it prints only the line that has the matching pattern only.

You can filter blank lines with the following pattern:

Here we introduce the negation which you can do it by the exclamation mark !

The pattern searches for empty lines where nothing between the beginning and the end of the line and negates that to print only the lines have text.

The dot character

We use the dot character to match any character except the newline (\n).

Look at the following example to get the idea:

You can see from the result that it prints only the first two lines because they contain the st pattern while the third line does not have that pattern, and the fourth line starts with st, so that also doesn’t match our pattern.

Character classes

You can match any character with the dot special character, but what if you match a set of characters only, you can use a character class.

The character class matches a set of characters if any of them found, the pattern matches.

We can define the character classes using square brackets [] like this:

Here we search for any th characters that have o character or i before it.

This comes handy when you are searching for words that may contain upper or lower case, and you are not sure about that.

Of course, it is not limited to characters; you can use numbers or whatever you want. You can employ it as you want as long as you got the idea.

Negating character classes

What about searching for a character that is not in the character class?

To achieve that, precede the character class range with a caret like this:

So anything is acceptable except o and i.

Using ranges

To specify a range of characters, you can use the (-) symbol like this:

This matches all characters between e and p then followed by st as shown.

You can also use ranges for numbers:

You can use multiple and separated ranges like this:

The pattern here means from a to f, and m to z must appear before the st text.

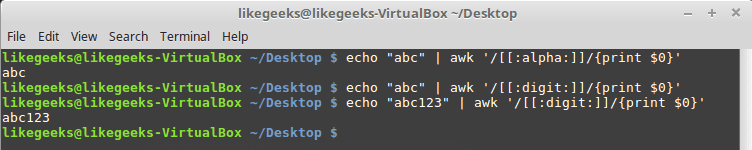

Special character classes

The following list includes the special character classes which you can use them:

| [[:alpha:]] | Pattern for any alphabetical character, either upper or lower case. |

| [[:alnum:]] | Pattern for 0–9, A–Z, or a–z. |

| [[:blank:]] | Pattern for space or Tab only. |

| [[:digit:]] | Pattern for 0 to 9. |

| [[:lower:]] | Pattern for a–z lower case only. |

| [[:print:]] | Pattern for any printable character. |

| [[:punct:]] | Pattern for any punctuation character. |

| [[:space:]] | Pattern for any whitespace character: space, Tab, NL, FF, VT, CR. |

| [[:upper:]] | Pattern for A–Z upper case only. |

You can use them like this:

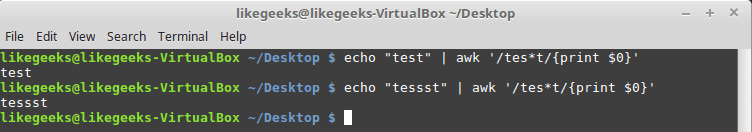

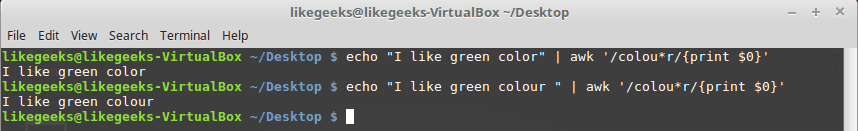

The asterisk

The asterisk means that the character must exist zero or more times.

This pattern symbol is useful for checking misspelling or language variations.

Here in these examples, whether you type it color or colour it will match, because the asterisk means if the “u” character existed many times or zero time that will match.

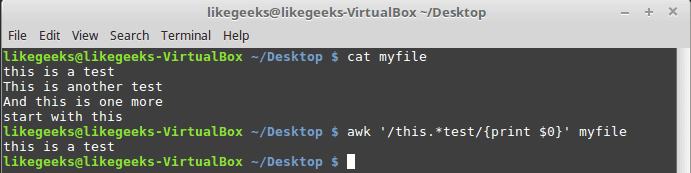

To match any number of any character, you can use the dot with the asterisk like this:

It doesn’t matter how many words between the words “this” and “test”, any line matches, will be printed.

You can use the asterisk character with the character class.

All three examples match because the asterisk means if you find zero times or more any “a” character or “e” print it.

Extended regular expressions

The following are some of the patterns that belong to Posix ERE:

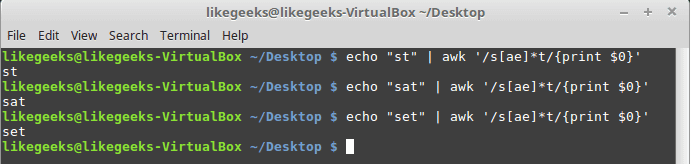

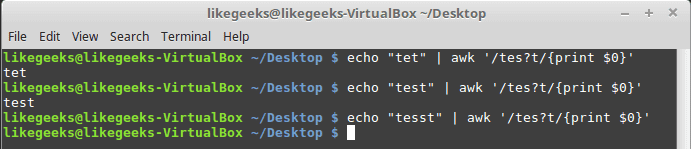

The question mark

The question mark means the previous character can exist once or none.

We can use the question mark in combination with a character class:

If any of the character class items exists, the pattern matching passes. Otherwise, the pattern will fail.

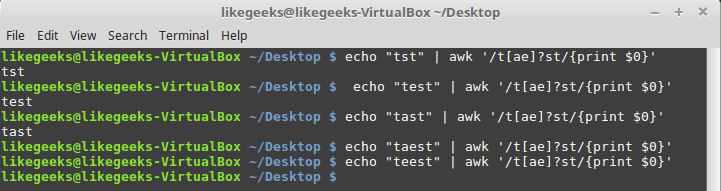

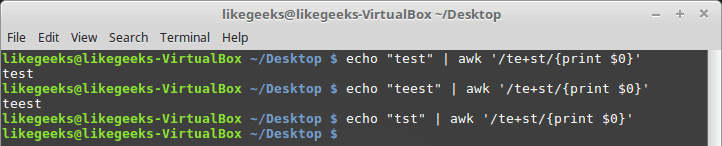

The plus sign

The plus sign means that the character before the plus sign should exist one or more times, but must exist once at least.

If the “e” character not found, it fails.

You can use it with character classes like this:

if any character from the character class exists, it succeeds.

Curly braces

Curly braces enable you to specify the number of existence for a pattern, it has two formats:

n: The regex appears exactly n times.

n,m: The regex appears at least n times, but no more than m times.

In old versions of awk, you should use –re-interval option for the awk command to make it read curly braces, but in newer versions, you don’t need it.

In this example, if the “e” character exists one or two times, it succeeds; otherwise, it fails.

You can use it with character classes like this:

If there are one or two instances of the letter “a” or “e”, the pattern passes; otherwise, it fails.

Pipe symbol

The pipe symbol makes a logical OR between 2 patterns. If one of the patterns exists, it succeeds; otherwise, it fails, here is an example:

Don’t type any spaces between the pattern and the pipe symbol.

Grouping expressions

You can group expressions so the regex engines will consider them one piece.

The grouping of the “Geeks” makes the regex engine treats it as one piece, so if “LikeGeeks” or the word “Like” exist, it succeeds.

Practical examples

We saw some simple demonstrations of using regular expression patterns. It’s time to put that in action, just for practicing.

Counting directory files

Let’s look at a bash script that counts the executable files in a folder from the PATH environment variable.

To get a directory listing, you must replace each colon with space.

Now let’s iterate through each directory using the for loop like this:

You can get the files on each directory using the ls command and save it in a variable.

You may notice some directories don’t exist, no problem with this, it’s OKay.

Cool!! This is the power of regex—these few lines of code count all files in all directories. Of course, there is a Linux command to do that very easily, but here we discuss how to employ regex on something you can use. You can come up with some more useful ideas.

Validating E-mail address

There are a ton of websites that offer ready to use regex patterns for everything, including e-mail, phone number, and much more, this is handy, but we want to understand how it works.

The username can use any alphanumeric characters combined with dot, dash, plus sign, underscore.

The hostname can use any alphanumeric characters combined with a dot and underscore.

For the username, the following pattern fits all usernames:

The plus sign means one character or more must exist followed by the @ sign.

Then the hostname pattern should be like this:

There are special rules for the TLDs or Top-level domains, and they must be not less than 2 and five characters maximum. The following is the regex pattern for the top-level domain.

Now we put them all together:

Let’s test that regex against an email:

This was just the beginning of the regex world that never ends. I hope you understand these ASCII pukes 🙂 and use it more professionally.

Источник