- LINUX File Extension

- What is LINUX file?

- Programs which support LINUX file extension

- Programs that support LINUX file

- How to open file with LINUX extension?

- Step 1. Get the Linux operating systems

- Step 2. Check the version of Linux operating systems and update if needed

- Step 3. Associate Linux files with Linux operating systems

- Step 4. Check the LINUX for errors

- File extensions and association with programs in linux

- 6 Answers 6

- Do file-extensions have any purpose (for the operating system)?

- 7 Answers 7

- However

LINUX File Extension

Linux

What is LINUX file?

LINUX is a file extension commonly associated with Linux files. Various Linux developers defined the Linux format standard. Files with LINUX extension may be used by programs distributed for Linux platform. LINUX file belongs to the Document Files category just like 574 other filename extensions listed in our database. Linux operating systems is by far the most used program for working with LINUX files. On the official website of Various Linux developers developer not only will you find detailed information about theLinux operating systems software, but also about LINUX and other supported file formats.

Programs which support LINUX file extension

The following listing features LINUX-compatible programs. LINUX files can be encountered on all system platforms, including mobile, yet there is no guarantee each will properly support such files.

Programs that support LINUX file

How to open file with LINUX extension?

There can be multiple causes why you have problems with opening LINUX files on given system. Fortunately, most common problems with LINUX files can be solved without in-depth IT knowledge, and most importantly, in a matter of minutes. The following is a list of guidelines that will help you identify and solve file-related problems.

Step 1. Get the Linux operating systems

Step 2. Check the version of Linux operating systems and update if needed

Step 3. Associate Linux files with Linux operating systems

If the issue has not been solved in the previous step, you should associate LINUX files with latest version of Linux operating systems you have installed on your device. The next step should pose no problems. The procedure is straightforward and largely system-independent

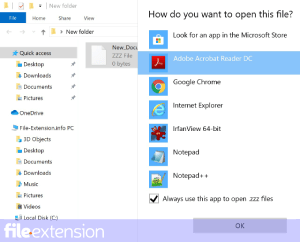

The procedure to change the default program in Windows

- Choose the Open with entry from the file menu accessed by right-mouse clicking on the LINUX file

- Select Choose another app в†’ More apps

- To finalize the process, select Look for another app on this PC entry and using the file explorer select the Linux operating systems installation folder. Confirm by checking Always use this app to open LINUX files box and clicking OK button.

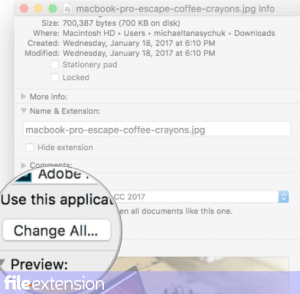

The procedure to change the default program in Mac OS

- By clicking right mouse button on the selected LINUX file open the file menu and choose Information

- Proceed to the Open with section. If its closed, click the title to access available options

- From the list choose the appropriate program and confirm by clicking Change for all. .

- A message window should appear informing that This change will be applied to all files with LINUX extension. By clicking Continue you confirm your selection.

Step 4. Check the LINUX for errors

If you followed the instructions form the previous steps yet the issue is still not solved, you should verify the LINUX file in question. Being unable to access the file can be related to various issues.

1. Check the LINUX file for viruses or malware

Should it happed that the LINUX is infected with a virus, this may be that cause that prevents you from accessing it. It is advised to scan the system for viruses and malware as soon as possible or use an online antivirus scanner. If the LINUX file is indeed infected follow the instructions below.

2. Verify that the LINUX file’s structure is intact

Did you receive the LINUX file in question from a different person? Ask him/her to send it one more time. It is possible that the file has not been properly copied to a data storage and is incomplete and therefore cannot be opened. If the LINUX file has been downloaded from the internet only partially, try to redownload it.

3. Verify whether your account has administrative rights

There is a possibility that the file in question can only be accessed by users with sufficient system privileges. Log out of your current account and log in to an account with sufficient access privileges. Then open the Linux file.

4. Check whether your system can handle Linux operating systems

The operating systems may note enough free resources to run the application that support LINUX files. Close all running programs and try opening the LINUX file.

5. Verify that your operating system and drivers are up to date

Regularly updated system, drivers, and programs keep your computer secure. This may also prevent problems with Linux files. It is possible that one of the available system or driver updates may solve the problems with LINUX files affecting older versions of given software.

Do you want to help?

If you have additional information about the LINUX file, we will be grateful if you share it with our users. To do this, use the form here and send us your information on LINUX file.

Источник

File extensions and association with programs in linux

In windows we can associate a file’s extension with programs.

E.g. a file test.pl can be run by the installed Perl interpreter due to the pl extension.

In linux though it needs #!/usr/bin/perl as the first line.

Is this because there is no association between file extensions and programs in Linux?

6 Answers 6

No, it doesn’t mean that. If you have a text-file that has it’s execute-permission set (e.g. chmod a+x somefile ), and the first line of the file is something like

It just tells Unix what program to use to execute the script. If a text-file is marked as an executable (i.e. is a script), Unix will start whatever program is specified in this way, and send the rest of the text-file (the script) to this program. Typically the program specified will be a shell ( /bin/sh , /bin/csh or /bin/bash ), the interpreter for some programming-language (Perl, Python or Ruby) or some other program that executes scripts (like the text-manipulators Awk or Sed).

Usually the «#» specify a comment in many languages, it’s only if the first line begins with «#!» it’s something special. If a file is marked as executable but doesn’t start with a «#!», Unix will assume it’s some kind of binary (e.g. an ELF-executable made by the C-compiler and linker).

In general Unix doesn’t rely on the suffix of files. Many programs neither needs nor automatically adds their typical suffixes, one exception being the compression-programs (like gzip and bzip2 ) which usually replaces the original file with a compressed one, adding a suffix to mark compression-type (these are one of the few programs that complains about incorrect suffix).

Instead the file is identified by it’s content through a series of tests, looking for «magic-numbers» and other identifiers (you can try the command file on some files to test this). This is also used by the file-browsers under GNOME and KDE to select icons and the list of programs to open/edit the file. Here the MIME-type of the file is identified by such tests, then the suitable programs for viewing and editing is found from a list associated to the MIME-type — not the suffix as in Windows.

Since one of the tests would be to check if the first line of a text-file is «#!/something», and then look at what «something» is; you could say for example that #!/usr/bin/perl identified the file as a perl-script — but that is more of a side-effect. Even if the file doesn’t start with a «#!», the tests should be able to correctly identify the file. In any case, it’s the content of the file that is used to identify it, not an arbitrary suffix. As such, endings like .pl (Perl) and .awk (Awk) is purely to help a human user to identify the type of file, it’s not used by Unix to determent type (like the suffixes in Windows).

You can actually make a «script» without the «#!/something», but Unix wouldn’t be able to automatically run it as an executable (it wouldn’t know what program to run the script in). Instead you’d have to «manually» start it with something like perl myscript or python myscript . Many scripts in larger Python and Perl applications will actually not start with «#!/something», as they’re scripts for «internal use» and not intended to be invoked by the user directly.

Instead you’ll start the main script (which does start with a «#!/something»), and then it will pass these other scripts to the interpreter as this script runs.

Источник

Do file-extensions have any purpose (for the operating system)?

Linux determines the type of a file via a code in the file-header. It doesn’t depend on file-extensions for to know which software is to use for opening the file.

That’s what I remember from my education. Please correct me in case I’m wrong!

Working a bit with Ubuntu systems recently: I see a lot of files on the systems which have extensions like .sh , .txt , .o , .c

Now I’m wondering: Are these extensions are meant only for humans? So that one should get an idea what kind of file it is?

Or does they have some purpose for the operating-system too?

7 Answers 7

There is no 100% black or white answer here.

Usually Linux does not rely on file names (and file extensions i.e. the part of the file name after the normally last period) and instead determines the file type by examining the first few bytes of its content and comparing that to a list of known magic numbers.

For example all Bitmap image files (usually with name extension .bmp ) must start with the letters BM in their first two bytes. Scripts in most scripting languages like Bash, Python, Perl, AWK, etc. (basically everything that treats lines starting with # as comment) may contain a shebang like #!/bin/bash as first line. This special comment tells the system with which application to open the file.

So normally the operating system relies on the file content and not its name to determine the file type, but stating that file extensions are never needed on Linux is only half of the truth.

Applications may of course implement their file checks however they want, which includes verifying the file name and extension. An example is the Eye of Gnome ( eog , standard picture viewer) which determines the image format by the file extension and throws an error if it does not match the content. Whether this is a bug or a feature can be discussed.

However, even some parts of the operating system rely on file name extensions, e.g. when parsing your software sources files in /etc/apt/sources.list.d/ — only files with the *.list extension get parsed all others are ignored. It’s maybe not mainly used to determine the file type here but rather to enable/disable parsing of some files, but it’s still a file extension that affects how the system treats a file.

And of course the human user profits most from file extensions as that makes the type of a file obvious and also allows multiple files with the same base name and different extensions like site.html , site.php , site.js , site.css etc. The disadvantage is of course that file extension and the actual file type/content do not necessarily have to match.

Additionally it’s needed for cross-platform interoperability, as e.g. Windows will not know what to do with a readme file, but only a readme.txt .

Linux determines the type of a file via a code in the file header. It doesn’t depend on file extensions for to know with software is to use for opening the file.

That’s what I remember from my education. Please correct me in case I’m wrong!

Are these extensions are meant only for humans?

When you interact with other operating systems that do depend on extensions being what they are it is the smarter idea to use those.

In Windows, opening software is attached to the extensions.

Opening a text file named «file» is harder in Windows than opening the same file named «file.txt» (you will need to switch the file open dialog from *.txt to *.* every time). The same goes for TAB and semi-colon separated text files. The same goes for importing and exporting e-mails (.mbox extension).

In particular when you code software. Opening a file named «software1» that is an HTML file and «software2» that is a JavaScript file becomes more difficult compared to «software.html» and «software.js».

If there is a system in place in Linux where file extensions are important, I would call that a bug. When software depends on file extensions, that is exploitable. We use an interpreter directive to identify what a file is («the first two bytes in a file can be the characters «#!», which constitute a magic number (hexadecimal 23 and 21, the ASCII values of «#» and «!») often referred to as shebang,»).

The most famous problem with file extensions was LOVE-LETTER-FOR-YOU.TXT.vbs on Windows. This is a visual basic script being shown in file explorer as a text file.

In Ubuntu when you start a file from Nautilus you get a warning what it is going to do. Executing a script from Nautilus where it wants to start some software where it is supposed to open gEdit is obvious a problem and we get a warning about it.

In command line when you execute something, you can visually see what the extension is. If it ends on .vbs I would start to become suspicious (not that .vbs is executable on Linux. At least not without some more effort 😉 ).

As mentioned by others, in Linux an interpreter directive method is used (storing some metadata in a file as a header or magic number so the correct interpreter can be told to read it) rather than the filename extension association method used by Windows.

This means you can create a file with almost any name you like. with a few exceptions

However

I would like to add a word of caution.

If you have some files on your system from a system that uses filename association, the files may not have those magic numbers or headers. Filename extensions are used to identify these files by applications that are able to read them, and you may experience some unexpected effects if you rename such files. For example:

If you rename a file My Novel.doc to My-Novel , Libreoffice will still be able to open it, but it will open as ‘Untitled’ and you will have to name it again in order to save it (Libreoffice adds an extension by default, so you would then have two files My-Novel and My-Novel.odt , which could be annoying)

More seriously, if you rename a file My Spreadsheet.xlsx to My-Spreadsheet, then try to open it with xdg-open My-Spreadsheet you will get this (because it’s actually a compressed file):

And if you rename a file My Spreadsheet.xls to My-Spreadsheet , when you xdg-open My-Spreadsheet you get an error saying

error opening location: No application is registered as handling this file

(Although in both these cases it works OK if you do soffice My-Spreadsheet )

If you then rename the extensionless file to My-Spreadsheet.ods with mv and try to open it you will get this:

And you will have to put the original extension back on to open the file correctly (you can then convert the format if you wish)

If you have non-native files with name extensions, don’t remove the extensions assuming everything will be OK!

I’d like to take a different approach to this from other answers, and challenge the notion that «Linux» or «Windows» have anything to do with this (bear with me).

The concept of a file extension can be simply expressed as «a convention for identifying the type of a file based on part of its name». The other common conventions for identifying the type of a file are comparing its contents against a database of known signatures (the «magic number» approach), and storing it as an extra attribute on the file system (the approach used in the original MacOS).

Since every file on a Windows or a Linux system has both a name and contents, processes which want to know the file type can use either the «extension» or the «magic number» approaches as they see fit. The metadata approach is not generally available, as there is no standard place for this attribute on most file systems.

On Windows, there is a strong tradition of using the file extension as the primary means of identifying a file; most visibly, the graphical file browser (File Manager on Windows 3.1 and Explorer on modern Windows) uses it when you double-click on a file to determine which application to launch. On Linux (and, more generally, Unix-based systems), there is more tradition for inspecting the contents; most notably, the kernel looks at the beginning of a file executed directly to determine how to run it; script files can indicate an interpreter to use by starting with #! followed by the path to the interpreter.

These traditions influence UI design of programs written for each system, but there are plenty of exceptions, because each approach has pros and cons in different situations. Reasons to use file extensions rather than examining contents include:

- examining file contents is fairly costly compared to examining file names; so for instance «find all files named *.conf» will be a lot quicker than «find all files whose first line matches this signature»

- file contents can be ambiguous; many file formats are actually just text files treated in a special way, many others are specially-structured zip files, and defining accurate signatures for these can be tricky

- a file can genuinely be valid as more than one type; an HTML file may also be valid XML, a zip file and a GIF concatenated together remain valid for both formats

- magic number matching might lead to false positives; a file format that has no header might happen to begin with the bytes «GIF89a» and be misidentified as a GIF image

- renaming a file can be a convenient way to mark it as «disabled»; e.g. changing «foo.conf» to «foo.conf

» to indicate a backup is easier than editing the file to comment out all of its directives, and more convenient than moving it out of an autoloaded directory; similarly, renaming a .php file to .txt will tell Apache to serve its source as plain text, rather than passing it to the PHP engine

Examples of Linux programs which use file names by default (but may have other modes):

- gzip and gunzip have special handling of any file ending «.gz»

- gcc will handle «.c» files as C, and «.cc» or «.C» as C++

Источник