- User mode and kernel mode

- Single-User Mode in Windows?

- 3 Answers 3

- What is “Windows 10 in S Mode”? Can I Change it to Regular Windows?

- What Is Windows 10 In S Mode?

- Security In Windows 10 S Mode

- Speed In Windows 10 S Mode

- Size & Windows 10 S Mode

- Windows 10 S Mode For Schools

- Why Are More Laptops Being Sold As Windows Running In S Mode?

- How To Change From S Mode To Full Windows Mode

- Can We Go Back to Windows in S Mode?

- Software Development in Windows

- Windows Evolution

- Windows Release History

- Supported CPU Architectures

- Windows Build Flavors

- Windows Servicing Terminology

User mode and kernel mode

A processor in a computer running Windows has two different modes: user mode and kernel mode. The processor switches between the two modes depending on what type of code is running on the processor. Applications run in user mode, and core operating system components run in kernel mode. While many drivers run in kernel mode, some drivers may run in user mode.

When you start a user-mode application, Windows creates a process for the application. The process provides the application with a private virtual address space and a private handle table. Because an application’s virtual address space is private, one application cannot alter data that belongs to another application. Each application runs in isolation, and if an application crashes, the crash is limited to that one application. Other applications and the operating system are not affected by the crash.

In addition to being private, the virtual address space of a user-mode application is limited. A processor running in user mode cannot access virtual addresses that are reserved for the operating system. Limiting the virtual address space of a user-mode application prevents the application from altering, and possibly damaging, critical operating system data.

All code that runs in kernel mode shares a single virtual address space. This means that a kernel-mode driver is not isolated from other drivers and the operating system itself. If a kernel-mode driver accidentally writes to the wrong virtual address, data that belongs to the operating system or another driver could be compromised. If a kernel-mode driver crashes, the entire operating system crashes.

This diagram illustrates communication between user-mode and kernel-mode components.

Single-User Mode in Windows?

I’ve used Single-User Mode on my Mac and I find it quite useful and educational. Is there a Windows equivalent?

Part of the reason I want a Windows equivalent is because from Single-User Mode, I was able to reset the admin password and regain control of the computer. I’d like to see if I can replicate this effect on my PC.

3 Answers 3

Windows is built somewhat completely different to mac/linux and there is no real single user mode.

If you need to reset an administrator account, there are a couple of things you can try:

1)Reboot your computer and as your BIOS screen shows, keep tapping F8 on your keyboard. This will bring up a menu option list — one of which will be «Safe Mode». From here you should be able to login and change an administrators password. The easiest way to do this is to load C:\windows\system32\lusrmgr.msc and find your user.

2)Look at some offline password editors. Some of the most commonly used ones are mtnioned in this article and include:

- ophCrack

- Offline NT Password & Registry Editor

- PC Login Now ..and many more

3)look into the possibility of resetting your computer — this is a bit more extreme and will reset windows to its «out of the box» settings. including removal of user passwords. This, however, also removes user accounts, apps, data as well — only really to be used as a last resort and only if you have a recent data backup. To complete the Reset Your PC process, access Advanced Startup Options and then choose Troubleshoot -> Reset Your PC.

What is “Windows 10 in S Mode”? Can I Change it to Regular Windows?

We explain all, plus give you a warning

Microsoft has done some weird things with Windows over the years. Windows running in S Mode is one of those things.

More and more, we find laptops listed as having Windows 10 running in S Mode, but there’s no explanation of S Mode. There’s also nothing in the laptop ads to let us know that we can take Windows out of S Mode and have a regular version of Windows 10.

What Is Windows 10 In S Mode?

As the name suggests, it’s a mode of Windows 10 as opposed to being its own operating system (OS).

It’s not public knowledge yet what the S stands for, but based on their marketing, it could be for Security, Speed, Smaller, or even Schools. Maybe all of those. Windows OS names have been cryptic.

Security In Windows 10 S Mode

Windows 10 S Mode is marketed as being more secure than the full Windows 10. It only allows for installing Microsoft verified apps from the Microsoft Store. That does limit the number of apps available, but it shouldn’t limit us from what we can do.

As of the end of September 2019, there were over 669,000 apps in the Microsoft Store. We should be able to find what we need. All our everyday apps, like Spotify, Slack, NetFlix, and the Microsoft Office Suite are there.

S Mode also uses the Microsoft Edge browser as the default web browser, and it cannot be changed. Microsoft is clinging on to the 2017 NSS Labs Web Browser Security Report stating that Edge is more secure than Chrome or Firefox. That report is 3 years old, so it’s up for debate.

Working in PowerShell, CMD, and tweaking the Windows Registry is also stripped out of Windows 10 in S Mode for greater security. Basically, if it’s an administrator-level tool, it’s not in S Mode, making it that much harder to hack.

Speed In Windows 10 S Mode

Microsoft also says the Windows 10 S Mode has greater speed. Well, at least at startup. It’s a reasonable claim that if it doesn’t have to load the full bloat of Windows 10, it will start up faster than full Windows 10.

The Edge web browser is the default browser for S Mode, and Microsoft argues that it’s faster than Chrome or Firefox for browsing. Again, that’s debatable as there are too many factors involved in web browsing to make a definitive, objective claim like that.

Size & Windows 10 S Mode

In a game of size-does-matter, Windows running in S Mode has an installed size of about 5GB on the hard drive. A Windows 10 full-installation can range from about 20GB to 40GB, depending on the edition and features chosen. S Mode saves us at least 15GB of drive space.

As we’ll see below, S Mode is also likely to run well on the absolute minimum system requirements of Windows 10.

Windows 10 S Mode For Schools

The education market is a key to OS dominance. Whatever OS young people first use is likely to be the OS that they’ll prefer later in life. Whatever OS schools are using to teach work skills is likely to be the OS that employers will use so young employees can be productive and quicker. That’s a big part of how Microsoft became what it is today.

Google knows that and has been getting its small, fast, affordable Chromebooks into schools in droves. S Mode is Microsoft’s counter to that.

Windows 10 S Mode’s speed, security, and even size suit the school market. Plus, S Mode comes with education-specific support with administrator tools like the Set Up School PCs app. There’s also the Microsoft Educator Center, where teachers can learn more about Microsoft products and how best to use them in the classroom.

The lighter OS should also use less power, making for longer battery life. The idea being that a student could use it all day without recharging it.

Why Are More Laptops Being Sold As Windows Running In S Mode?

We suspect it is because they can sell a laptop with lower-end hardware if Windows is installed in S Mode. That’s not a bad thing! If people need a Windows computer but can’t afford a full-featured laptop, this helps lower the entry barrier. It makes a Windows device a contender against Chrome devices.

Full Windows 10 and Windows running in S Mode have the same minimum system requirements to be installed.

- The device needs at least a 1 gigahertz (GHz) processor or System on a Chip (SoC).

- There must be a minimum of 2GB of RAM and 32GB of hard drive space.

- It must have DirectX 9 or later compatible graphics card and display resolution of at least 800×600 pixels.

- The only extra requirement Windows 10 S Mode requires is that the device is able to connect to the Internet on the initial set up.

We know that if we had a laptop with those minimum specifications and tried to use Windows 10 Home, Pro, or Enterprise on it, we’d be pulling our hair out very quickly. It would be next to useless. So, we get computers with far greater specifications at a far greater cost.

Windows 10 in S Mode is likely to run just fine on those minimum specifications. A device built at, or close to, those minimum specs are going to be far more affordable than the full-featured laptops costing hundreds or even thousands of dollars.

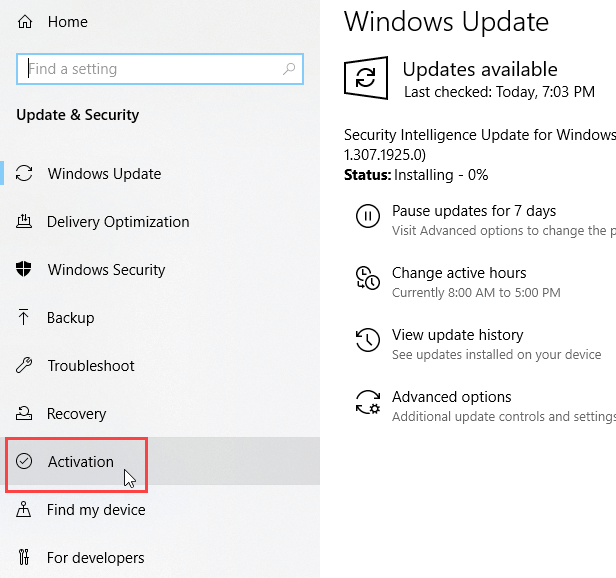

How To Change From S Mode To Full Windows Mode

Now that we know what Windows 10 S Mode is, we don’t need to fear that we’re not getting the full Windows experience. If we want to use the full version of our Windows OS, we can take it out of S Mode and go into regular more anytime we want to. There’s no extra cost either. Just be sure that your device can handle it.

The most important warning is that once we switch to full Windows mode, we cannot easily go back to S Mode. If we created restoration media with the device when we got it, then we can restore the computer to S Mode.

There has been chatter on the Internet about Microsoft eventually including a way to easily switch back and forth, but there is no official notice about that happening yet.

- Press the Windows and X keys at the same time. In the menu that opens, click on Settings.

- In the Settings window, click on Update and Security.

- In the Update window, click on Activation on the left-hand side.

- Look for the section Switch to Windows 10 Home or Switch to Windows 10 Pro, click on Go to the Store.

- The Microsoft Store will open to the Switch out of S Mode page. Click on the Get button. After a few seconds, there will be a confirmation message showing that the process is done. The computer will now be using the full Windows 10 Home or Windows 10 Pro. Programs other than apps from the Windows Store can be installed, too.

Can We Go Back to Windows in S Mode?

No, in case it was missed before, rolling back to Windows 10 in S Mode cannot be done. At best, the computer could be completely reset if we have the restoration media from when it was in Windows S Mode.

Guy has been published online and in print newspapers, nominated for writing awards, and cited in scholarly papers due to his ability to speak tech to anyone, but still prefers analog watches. Read Guy’s Full Bio

Software Development in Windows

In this chapter

- Windows Evolution 3

- Windows Architecture 7

- Windows Developer Interface 16

- Microsoft Developer Tools 28

- Summary 30

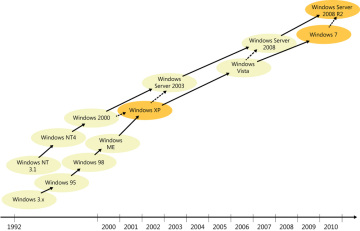

Windows Evolution

Though this book focuses primarily on the post-Vista era of Windows, it’s useful to look back at the history of Windows releases, because the roots of several building blocks of the underlying architecture can be traced all the way back to the Windows NT (an abbreviation for “New Technology”) operating system. Windows NT was first designed and developed by Microsoft in the late ’80s, and continued to evolve until its kernel finally became the core of all client and server versions of the Windows operating system.

Windows Release History

Windows XP marked a major milestone in the history of Windows releases by providing a unified code base for both the business (server) and consumer (client) releases of Windows. Though Windows XP was a client release (its server variant was Windows Server 2003), it technically succeeded both Windows 95/98/ME (a lineage of consumer operating systems that find their roots in the MS-DOS and Windows 3.1 operating systems) and Windows NT 4/Windows 2000, combining for the first time the power of the Windows NT operating system kernel and its robust architecture with many of the features that had made Windows 95 and Windows 98 instant hits with consumers and developers alike (friendly user design, aesthetic graphical interface, plug and play model, rich Win32 and DirectX API sets, and so on).

Though both the server and client releases of Windows now share the same kernel, they still differ in many of their features and components. (For example, only the server releases of Windows support multiple concurrent remote desktop user sessions.) Since the release of Windows XP in 2001, Windows Server has followed a release cycle that can be loosely mapped to corresponding Windows client releases. Windows Server 2003, for instance, shares many of the new kernel and API features that were added in Windows XP. Similarly, Windows Server 2008 R2 represents the server variant of Windows 7, which was released in late 2009. (Don’t confuse this with Windows Server 2008, which is the server variant of Windows Vista.)

Figure 1-1 illustrates the evolution of the Windows family of operating systems, with their approximate release dates relative to each other.

Figure 1-1 Timeline of major client and server releases of the Windows operating system since the early 90s.

Supported CPU Architectures

Windows was ported to many CPU architectures in the past. For example, Windows NT supported Alpha and MIPS processors until Windows NT 4. Windows NT 3.51 also had support for Power PC (another RISC family of processors that is used in many embedded devices, including, for example, Microsoft Xbox 360). However, Windows later narrowed its support to three CPU architectures: x86 (a 32-bit family of processors, whose instruction set was designed by Intel), x64 (also known as AMD-64, in reference to the fact this architecture was first introduced by AMD, though Intel also now releases processors implementing this instruction set), and ia64 (another 64-bit instruction set designed by Intel in collaboration with Hewlett-Packard).

Microsoft shipped the first ia64 version of Windows XP in late 2001 and followed it with an x64 version in 2005. Microsoft later dropped support for ia64 on client editions, including Windows XP. The x86, x64, and ia64 architectures supported in Windows Server 2003 and Windows XP are exactly those that were also supported when Windows Server 2008 R2 and Windows 7 shipped at the end of 2009, though x86 and x64 are clearly the more widely used Windows architectures nowadays. Note, however, that Windows Server no longer supports x86; it now supports only 64-bit architectures. Also, Microsoft announced early in 2011 that its upcoming release of the Windows operating system will be capable of running on ARM (in addition to the x86 and x64 platforms), a RISC instruction set that’s widely used in embedded utilities, smartphones, and tablet (slate) devices thanks in large part to its efficient use of battery power.

Understanding the underlying CPU architecture of the Windows installation you are working on is very important during debugging and tracing because you often need to use native tools that correspond to your CPU architecture. In addition, sometimes you will also need to understand the disassembly of the code you are analyzing in the debugger, which is different for each CPU. This is one reason many debugger listings in this book also show the underlying CPU architecture that they were captured on so that you can easily conduct any further disassembly inspection you decide to do on the right target platform. In the following listing, for example, the vertarget command shows a Windows 7 AMD64 (x64) operating system. You’ll see more about this command and others in the next chapter, so don’t worry about how to issue it for now.

Given the widespread use of x86 and x64, and because you can also execute x86 programs on x64 machines, the majority of experiments in this book are conducted using the x86 architecture so that you can follow them the way they’re described in this book regardless of your target architecture. Though x86 has been the constant platform of choice for Windows since its early days in the ’80s, 64-bit processors continue to gain in popularity even among home computers and laptops, which now often carry x64 versions of Windows 7.

Windows Build Flavors

The vertarget debugger command output shown in the previous section referred to the Windows version on the target machine as a “free” (also known as retail) build. This flavor is the only one ever shipped to end users by Microsoft for any of the supported processor architectures. There is, however, another flavor called a “checked” (also known as debug) build, which MSDN subscribers can obtain from Microsoft if they want to test the software they build with this flavor of the Windows operating system. It’s important to realize that checked flavors are mostly meant to help driver developers; they don’t derive their name at all from being “tested” or otherwise “checked” more thoroughly than the free flavors.

If you recall, the Introduction of this book recommended using the Driver Development Kit (DDK) build environment if you wanted to recompile the companion C++ sample code. As was explained then, you can also specify the build flavor you want to target (the default being x86 free in the Windows 7 DDK) when starting a DDK build environment. This is, in fact, also how the checked flavor of Windows is built internally at Microsoft because the same build environment made available in the DDK is also used by Windows developers to compile the Windows source code. For example, the following command starts a DDK build environment where your source code is compiled into x64 binaries using the checked (chk) build flavor. This essentially turns off a few compiler optimizations and defines debug build macros (such as the DBG preprocessor variable) that turn on “debug” sections of the code, including assertions (such as the NT_ASSERT macro).

Naturally, you don’t really need a checked build of Windows to run your checked binaries, and the main difference between your “free” and “checked” binaries is that the assertions you put in your code will occur only in the “checked” flavor. The benefit of the checked flavor of Windows itself is that it also contains many additional assertions in the system code that can point out implementation problems in your code, which is usually useful if you are developing a driver. The drawback to that Windows flavor, of course, is that it runs much slower than the free flavor and also that you must run it with a kernel debugger attached at all times so that you can ignore assertions when they’re hit; otherwise, those assertions might go unhandled and cause the machine to crash and reboot if they are raised in code that runs in kernel mode.

Windows Servicing Terminology

Each major Windows release is usually preceded by a few public milestones that provide customers with a preview of the features included in that release. Those prerelease milestones are usually called Alpha, Beta1, Beta2, and RC or release candidate, in this chronological order, though several Windows releases have either skipped some of these milestones or named them differently. These prerelease milestones also present an opportunity for Microsoft to engage with customers and collect their feedback before Windows is officially “released to manufacturing,” a milestone referred to as RTM.

You will again recognize the major version of Windows in the build information displayed by the vertarget command that accompanies many of the debugger listings presented in this book. For example, the following listing shows that the target machine is running Windows 7 RTM and that July 13, 2009 (identified by the “090713” substring in the following output) is the date this particular Windows build was produced at Microsoft.

In addition to the major client and server releases for each Windows operating system, Microsoft also ships several servicing updates in between those releases that get automatically delivered via the Windows Update pipeline and usually come in one of the following forms:

Service packs These releases usually occur a few years apart after RTM and compile the smaller updates made in between (and, on occasion, new features requested by customers) into a single package that can be applied at once by both consumers and businesses. They are often referred to using the “SP” abbreviation, followed by the service pack number. For example, SP1 is the first service pack after RTM, SP2 is the second, and so on.

Service packs are considered major releases and are subjected to the same rigorous release process that accompanies RTM releases. In fact, many Windows service packs also have one or more release candidate (RC) milestones before they’re officially released to the public. The number of service packs for a major Windows release is often determined by customer demand and also the amount of changes accumulated since the last service pack. Windows NT4, for example, had six service packs, while Windows Vista had two.

GDR updates GDR (General Distribution Release) updates are issued to address bugs with broad impact or security implications. The frequency varies by need, but these updates are usually released every few weeks. These fixes are also rolled up into the following service pack release.

For example, the following output indicates that the target debugging machine is running a version of Windows 7 SP1. Notice also that the version of kernel32.dll that’s installed on this machine comes from a GDR update subsequent to the initial Windows 7 SP1 release.