- Windows means in computers

- Computer Basics —

- Understanding Operating Systems

- Computer Basics: Understanding Operating Systems

- Lesson 8: Understanding Operating Systems

- What is an operating system?

- The operating system’s job

- Types of operating systems

- Microsoft Windows

- macOS

- Linux

- Operating systems for mobile devices

- Microsoft’s Windows operating system

- Workstation computers

- Living in cyberspace

- Ever smaller computers

- Embedded systems

- Handheld digital devices

Windows means in computers

Microsoft Windows

A mouse with modest requirements

by Phil Lemmons

The desktop metaphor and the mouse present attractive concepts, but Apple’s Lisa or IBM’s PC XT running Visi On exceeds the budget of the average personal computer user. Both of these systems require a hard disk and great quantities of RAM (random-access read/write memory). Although the mouse itself is a small part of the expense, it is a symbol of this approach to software, and some computer users have been heard to mutter, «What price mice?»

Another factor keeping down the mouse population has been the shortage of things for them to point at (or the shortage of application software). Until there is a large installed base of Lisa and Visi On systems, many software authors will forgo the expense of developing applications programs for these systems. Prospective buyers of personal computers, on the other hand, are unlikely to buy a Lisa or Visi On until more software is available. Apple’s own software for Lisa is magnificent, but other applications programs are only now emerging. Visicorp is making a major effort to induce programmers to write more for Visi On, but the requirements of a Unix development system is an obstacle to the smaller software houses and independent designers. The expense underlying the Unix development system is the hardware required to run it — once again, lots of memory and a hard disk.

This keeps most of us staring a the MS-DOS or CP/M command line and hoping that a sudden fall in the prices of RAM and hard disk will open the way to metaphors and mice. With the introduction of Microsoft Windows, however, the company that brought us MS-DOS promises a mouse-and-window show running off two 320K-byte floppy disks and 192K bytes of RAM. (More RAM is required, of course, with each additional application.) To make Microsoft Windows even more attractive to personal computer users, Microsoft promises to price Windows «as an operating-system component» — that is, inexpensively.

The economics of Microsoft Windows will also appeal to programmers. Programmers don’t need to buy special hardware or to learn Unix in order to develop software that runs under Microsoft Windows — they can user their own IBM Personal Computers. Moreover, programmers can take advantage of the ability to customize windows so that each software house retains its own distinct look within the Microsoft environment. The same enlightened attitude enabled Microsoft to resist the temptation to reserve Windows as an environment for its own applications programs. Microsoft is making Windows available to a number of applications software houses, including some major competitors.

Microsoft Windows is an installable device driver under MS-DOS 2.0 using ordinary MS-DOS files. Complete compatibility with MS-DOS means that Windows will at least let you run any application that runs under MS-DOS. In the worst case, Windows will turn the fill display over to an MS-DOS application and return you to your place in Windows. «Language bindings» will enable programmers to write software for Microsoft Windows in any Microsoft programming language.

Running Microsoft Windows

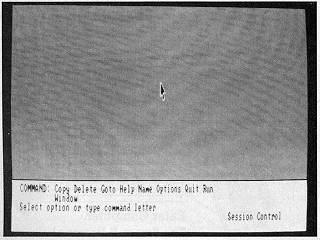

Photos 1-13 show a sequence of operations in Microsoft Windows. The photos on pages 52-53 show a variety of machines whose manufactures have adopted Microsoft Windows as an applications environment.

During normal use, Microsoft Windows displays one or more windows, each with a different application. You can move the cursor from one windows to another. You can move windows, change their size, scroll, get help appropriate to the context in which you are working, and transfer data among windows. Windows determines the highest level of data transfer mutually acceptable to the two applications, with plain ASCII (American National Standard Code for Information Interchange) as the last resort.

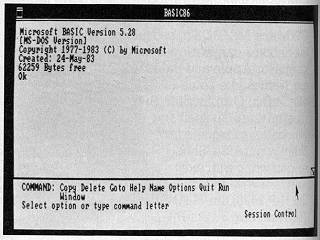

The «session-control layer» becomes the equivalent of the empty desktop where you can manipulate files. The available commands appear near the bottom of the screen. Normally, Microsoft Windows will restore the desktop to the state at the time of its last use. In photo 1, we start from scratch.

To see the available applications programs, you either use the mouse to position the cursor on the command «Run» or type the letter «R.» Windows lists all the applications programs as commands, and you point at the desired program and click the mouse to run it. You could also type the appropriate letter instead.

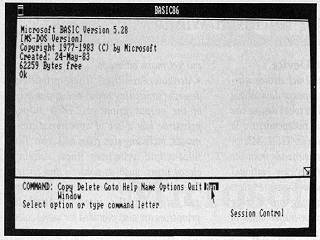

In photo 2, BASIC 86 is running in a large window extending the full width of the desktop. Because BASIC 86 does all its input/output through MS-DOS, it can run in a Window. Microsoft calls such software «co-operative.» The bottom of the screen shows the commands available in the session-contol layer. You can use the session-contol layer to run another program in parallel with BASIC 86.

The first step toward running a program is shown in photo 3, where the cursor points at «Run.» Microsoft Windows will now display a list of the programs available.

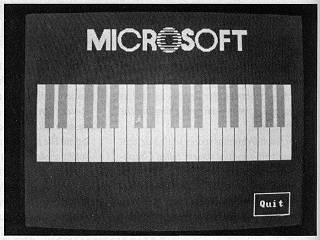

Photo 4 shows the next application selected. In this case, the program that’s run is «uncooperative» — that is, it doesn’t do everything through MS-DOS system calls, sometimes going beyond the operating system to write directly to the hardware addresses such as those of screen memory. Microsoft Windows can’t run such a program in a windows and must give it the entire screen. That is why photo 4 does not show the session control layer beneath the display of «Piano.»

Computer Basics —

Understanding Operating Systems

Computer Basics: Understanding Operating Systems

Lesson 8: Understanding Operating Systems

What is an operating system?

An operating system is the most important software that runs on a computer. It manages the computer’s memory and processes, as well as all of its software and hardware. It also allows you to communicate with the computer without knowing how to speak the computer’s language. Without an operating system, a computer is useless.

Watch the video below to learn more about operating systems.

Looking for the old version of this video? You can still view it here.

The operating system’s job

Your computer’s operating system (OS) manages all of the software and hardware on the computer. Most of the time, there are several different computer programs running at the same time, and they all need to access your computer’s central processing unit (CPU), memory, and storage. The operating system coordinates all of this to make sure each program gets what it needs.

Types of operating systems

Operating systems usually come pre-loaded on any computer you buy. Most people use the operating system that comes with their computer, but it’s possible to upgrade or even change operating systems. The three most common operating systems for personal computers are Microsoft Windows, macOS, and Linux.

Modern operating systems use a graphical user interface, or GUI (pronounced gooey). A GUI lets you use your mouse to click icons, buttons, and menus, and everything is clearly displayed on the screen using a combination of graphics and text.

Each operating system’s GUI has a different look and feel, so if you switch to a different operating system it may seem unfamiliar at first. However, modern operating systems are designed to be easy to use, and most of the basic principles are the same.

Microsoft Windows

Microsoft created the Windows operating system in the mid-1980s. There have been many different versions of Windows, but the most recent ones are Windows 10 (released in 2015), Windows 8 (2012), Windows 7 (2009), and Windows Vista (2007). Windows comes pre-loaded on most new PCs, which helps to make it the most popular operating system in the world.

Check out our tutorials on Windows Basics and specific Windows versions for more information.

macOS

macOS (previously called OS X) is a line of operating systems created by Apple. It comes preloaded on all Macintosh computers, or Macs. Some of the specific versions include Mojave (released in 2018), High Sierra (2017), and Sierra (2016).

According to StatCounter Global Stats, macOS users account for less than 10% of global operating systems—much lower than the percentage of Windows users (more than 80%). One reason for this is that Apple computers tend to be more expensive. However, many people do prefer the look and feel of macOS over Windows.

Check out our macOS Basics tutorial for more information.

Linux

Linux (pronounced LINN-ux) is a family of open-source operating systems, which means they can be modified and distributed by anyone around the world. This is different from proprietary software like Windows, which can only be modified by the company that owns it. The advantages of Linux are that it is free, and there are many different distributions—or versions—you can choose from.

According to StatCounter Global Stats, Linux users account for less than 2% of global operating systems. However, most servers run Linux because it’s relatively easy to customize.

To learn more about different distributions of Linux, visit the Ubuntu, Linux Mint, and Fedora websites, or refer to our Linux Resources. For a more comprehensive list, you can visit MakeUseOf’s list of The Best Linux Distributions.

Operating systems for mobile devices

The operating systems we’ve been talking about so far were designed to run on desktop and laptop computers. Mobile devices such as phones, tablet computers, and MP3 players are different from desktop and laptop computers, so they run operating systems that are designed specifically for mobile devices. Examples of mobile operating systems include Apple iOS and Google Android . In the screenshot below, you can see iOS running on an iPad.

Operating systems for mobile devices generally aren’t as fully featured as those made for desktop and laptop computers, and they aren’t able to run all of the same software. However, you can still do a lot of things with them, like watch movies, browse the Web, manage your calendar, and play games.

To learn more about mobile operating systems, check out our Mobile Devices tutorials.

Microsoft’s Windows operating system

In 1985 Microsoft came out with its Windows operating system, which gave PC compatibles some of the same capabilities as the Macintosh. Year after year, Microsoft refined and improved Windows so that Apple, which failed to come up with a significant new advantage, lost its edge. IBM tried to establish yet another operating system, OS/2, but lost the battle to Gates’s company. In fact, Microsoft also had established itself as the leading provider of application software for the Macintosh. Thus Microsoft dominated not only the operating system and application software business for PC-compatibles but also the application software business for the only nonstandard system with any sizable share of the desktop computer market. In 1998, amid a growing chorus of complaints about Microsoft’s business tactics, the U.S. Department of Justice filed a lawsuit charging Microsoft with using its monopoly position to stifle competition.

Workstation computers

While the personal computer market grew and matured, a variation on its theme grew out of university labs and began to threaten the minicomputers for their market. The new machines were called workstations. They looked like personal computers, and they sat on a single desktop and were used by a single individual just like personal computers, but they were distinguished by being more powerful and expensive, by having more complex architectures that spread the computational load over more than one CPU chip, by usually running the UNIX operating system, and by being targeted to scientists and engineers, software and chip designers, graphic artists, moviemakers, and others needing high performance. Workstations existed in a narrow niche between the cheapest minicomputers and the most powerful personal computers, and each year they had to become more powerful, pushing at the minicomputers even as they were pushed at by the high-end personal computers.

The most successful of the workstation manufacturers were Sun Microsystems, Inc., started by people involved in enhancing the UNIX operating system, and, for a time, Silicon Graphics, Inc., which marketed machines for video and audio editing.

The microcomputer market now included personal computers, software, peripheral devices, and workstations. Within two decades this market had surpassed the market for mainframes and minicomputers in sales and every other measure. As if to underscore such growth, in 1996 Silicon Graphics, a workstation manufacturer, bought the star of the supercomputer manufacturers, Cray Research, and began to develop supercomputers as a sideline. Moreover, Compaq Computer Corporation—which had parlayed its success with portable PCs into a perennial position during the 1990s as the leading seller of microcomputers—bought the reigning king of the minicomputer manufacturers, Digital Equipment Corporation (DEC). Compaq announced that it intended to fold DEC technology into its own expanding product line and that the DEC brand name would be gradually phased out. Microcomputers were not only outselling mainframes and minis, they were blotting them out.

Living in cyberspace

Ever smaller computers

Embedded systems

One can look at the development of the electronic computer as occurring in waves. The first large wave was the mainframe era, when many people had to share single machines. (The mainframe era is covered in the section The age of Big Iron.) In this view, the minicomputer era can be seen as a mere eddy in the larger wave, a development that allowed a favoured few to have greater contact with the big machines. Overall, the age of mainframes could be characterized by the expression “Many persons, one computer.”

The second wave of computing history was brought on by the personal computer, which in turn was made possible by the invention of the microprocessor. (This era is described in the section The personal computer revolution.) The impact of personal computers has been far greater than that of mainframes and minicomputers: their processing power has overtaken that of the minicomputers, and networks of personal computers working together to solve problems can be the equal of the fastest supercomputers. The era of the personal computer can be described as the age of “One person, one computer.”

Since the introduction of the first personal computer, the semiconductor business has grown to more than a quarter-trillion-dollar worldwide industry. However, this phenomenon is only partly ascribable to the general-purpose microprocessor, which accounts for about one-sixth of annual sales. The greatest growth in the semiconductor industry has occurred in the manufacture of special-purpose processors, controllers, and digital signal processors. These computer chips are increasingly being included, or embedded, in a vast array of consumer devices, including pagers, mobile telephones, music players, automobiles, televisions, digital cameras, kitchen appliances, video games, and toys. While the Intel Corporation may be safely said to dominate the worldwide microprocessor business, it has been outpaced in this rapidly growing multibillion-dollar industry by companies such as Motorola, Inc.; Hitachi, Ltd.; Texas Instruments Incorporated; NEC Corporation; and Lucent Technologies Inc. This ongoing third wave may be characterized as “One person, many computers.”

Handheld digital devices

The origins of handheld digital devices go back to the 1960s, when Alan Kay, a researcher at Xerox’s Palo Alto Research Center (PARC), promoted the vision of a small, powerful notebook-style computer that he called the Dynabook. Kay never actually built a Dynabook (the technology had yet to be invented), but his vision helped to catalyze the research that would eventually make his dream feasible.

It happened by small steps. The popularity of the personal computer and the ongoing miniaturization of the semiconductor circuitry and other devices first led to the development of somewhat smaller, portable—or, as they were sometimes called, luggable—computer systems. The first of these, the Osborne 1, designed by Lee Felsenstein, an electronics engineer active in the Homebrew Computer Club in San Francisco, was sold in 1981. Soon most PC manufacturers had portable models. At first these portables looked like sewing machines and weighed in excess of 20 pounds (9 kg). Gradually they became smaller (laptop-, notebook-, and then sub-notebook-size) and came with more powerful processors. These devices allowed people to use computers not only in the office or at home but also while traveling—on airplanes, in waiting rooms, or even at the beach.

As the size of computers continued to shrink and microprocessors became more and more powerful, researchers and entrepreneurs explored new possibilities in mobile computing. In the late 1980s and early ’90s, several companies came out with handheld computers, called personal digital assistants (PDAs). PDAs typically replaced the cathode-ray-tube screen with a more compact liquid crystal display, and they either had a miniature keyboard or replaced the keyboard with a stylus and handwriting-recognition software that allowed the user to write directly on the screen. Like the first personal computers, PDAs were built without a clear idea of what people would do with them. In fact, people did not do much at all with the early models. To some extent, the early PDAs, made by Go Corporation and Apple, were technologically premature; with their unreliable handwriting recognition, they offered little advantage over paper-and-pencil planning books.

The potential of this new kind of device was realized in 1996 when Palm Computing, Inc., released the Palm Pilot, which was about the size of a deck of playing cards and sold for about $400—approximately the same price as the MITS Altair, the first personal computer sold as a kit in 1974. The Pilot did not try to replace the computer but made it possible to organize and carry information with an electronic calendar, telephone number and address list, memo pad, and expense-tracking software and to synchronize that data with a PC. The device included an electronic cradle to connect to a PC and pass information back and forth. It also featured a data-entry system called “graffiti,” which involved writing with a stylus using a slightly altered alphabet that the device recognized. Its success encouraged numerous software companies to develop applications for it.

In 1998 this market heated up further with the entry of several established consumer electronics firms using Microsoft’s Windows CE operating system (a stripped-down version of the Windows system) to sell handheld computer devices and wireless telephones that could connect to PCs. These small devices also often possessed a communications component and benefited from the sudden popularization of the Internet and the World Wide Web. In particular, the BlackBerry PDA, introduced by the Canadian company Research in Motion in 2002, established itself as a favourite in the corporate world because of features that allowed employees to make secure connections with their company’s databases.

In 2001 Apple introduced the iPod, a handheld device capable of storing 1,000 songs for playback. Apple quickly came to dominate a booming market for music players. The iPod could also store notes and appointments. In 2003 Apple opened an online music store, iTunes Store, and in the following software releases added photographs and movies to the media the iPod could handle. The market for iPods and iPod-like devices was second only to cellular telephones among handheld electronic devices.

While Apple and competitors grew the market for handheld devices with these media players, mobile telephones were increasingly becoming “smartphones,” acquiring more of the functions of computers, including the ability to send and receive e-mail and text messages and to access the Internet. In 2007 Apple once again shook up a market for handheld devices, this time redefining the smartphone market with its iPhone. The touch-screen interface of the iPhone was in its way more advanced than the graphical user interface used on personal computers, its storage rivaled that of computers from just a few years before, and its operating system was a modified version of the operating system on the Apple Macintosh. This, along with synchronizing and distribution technology, embodied a vision of ubiquitous computing in which personal documents and other media could be moved easily from one device to another. Handheld devices and computers found their link through the Internet.